by Anne E. Johnson

Published April 28, 2024

Opera Lafayette’s Modern Premiere of Mouret’s ‘Les fêtes de Thalie‘

There’s “serious” art. There’s “fun” art. Are they the same thing? It’s not a new question, as the Washington, D.C.-based Opera Lafayette aims to prove with performances of Jean-Joseph Mouret’s comic opera-ballet Les fêtes de Thalie on May 3-4, 2024 (D.C.) and May 7, 2024 (New York). For their modern premiere of what was a popular work in the 18th century — the opera premiered in 1714 and was revised in 1720 — the company is taking this fun opera very seriously indeed.

“This is a terrific piece that I’ve known about for some time,” says Opera Lafayette Artistic Director and founder Ryan Brown. Thalie, Mouret’s first opera, was groundbreaking in a way. “There were a few comedy-ballets before this, but it hadn’t really been put on the stage in the same way,” says Brown, “and certainly hadn’t had the same glory as tragedies.”

This is the third consecutive Lafayette season dedicated to women who influenced the development of French opera. The first was Marie Antoinette in 2022, then Madame de Pompadour last year. The 2023-24 season has been devoted to the influence of Madame de Maintenon, a noblewoman who secretly married Louis XIV around 1683. As the king’s partner in his last decades (he died in 1715), she influenced his support of the arts. “Since she was rather religious,” says Brown, “Versailles [became] a pretty somber place. They patronized chamber music and some religious music, but there weren’t ‘entertainments’ any more at Versailles. Paris had to take up the slack.”

Madame de Maintenon was passionate about education, Brown explains: “She had a school for impoverished young aristocratic women.” To acknowledge that interest, Opera Lafayette commissioned essays from scholars for each of its productions. Cornell University musicologist Rebecca Harris-Warrick, author of the influential book Dance and Drama in French Baroque Opera, was asked to share her expertise in Mouret (1682-1738).

Harris-Warrick presents Mouret as a composer for the people and that he “was not aiming for the highest intellectual level. He was trying to please his audience. Later on, he went on to write for the Italian theater, where he really found his niche.” Thalie was influenced by commedia dell’arte, or comédie italienne, as the French called it.

In 1697, the Italian troupes were kicked out of Paris, says Harris-Warrick, “for reasons that may have to do with Madame de Maintenon. Their repertoire was taken over by theaters that [performed] in the seasonal fairs.” That’s where French comic opera was usually seen, often using stock characters from the Italian tradition, but with French texts.

What makes Mouret’s comedy historically significant is the fact that it was done on the stage rather than at a fair, and, just as significant, it was performed in Paris at the Académie Royal de Musique rather than at the court of Versailles, which had been the center of French opera throughout the domineering career of Jean-Baptiste Lully, who died in 1687.

Although living under the king’s control at Versailles, Harris-Warrick points out, members of the court frequented the big city. “They often had townhouses in Paris” and they of course needed to be entertained. “We tend to think of Italian-inflected repertoire as being lowbrow, crude, and [that] it must have had a lower-class audience. But that’s not the case. It had a very broad audience, including members of the royal family.”

Thalie’s prologue lacks the kind of encomium to the king that used to be standard, says Harris-Warrick. “The Paris Opera always had a double life. It always performed for the king, and it also performed as a public theater in Paris. You can tell by the prologue that, to a large extent, the king is becoming less relevant.”

The prologue is also notable because “it has a little meta-theatrical thing going on,” says artistic director Brown, meaning that it’s theater about theater. “The muse of tragedy comes out and says, ‘This is my stage. This is my theater and my glory.’ And then Thalie, the muse of comedy, shows up and says, Not tonight, it isn’t.” At issue is whether comedy belongs on the opera stage at all.

This self-analysis is a framing device. The epilogue, added in 1720, is called “La critique.” “Thalie makes a surprise appearance at the end and says, ‘We have won! We’ve brought comedy to the stage!’” says Brown. Three muses represent earthly aspects of the opera industry: Polyhymnia, muse of music, stands for the composer of serious opera; Thalie, muse of comedy, is the librettist; Terpsichore, muse of dance, is the choreographer. “They all argue about who gets the credit for the success of the evening.”

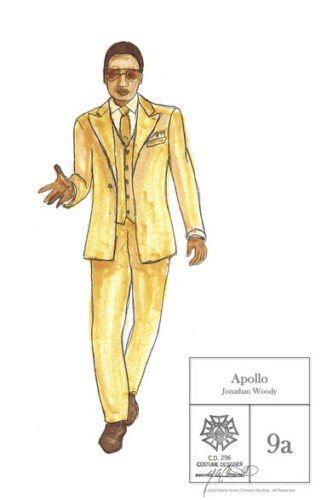

The god Apollo, who can’t be bothered to make a judgment, sends them Momus, god of mockery — the music critic. Momus complains about aspects of everyone’s work before eventually letting them share the prize. “In the original libretto, they all get laurels,” says Catherine Turocy, Thalie’s stage director, “but in our libretto they’ll get some kind of Oscar.”

Turocy sees parallels with today’s society. “In our modern times we’re still dealing with some of the same issues in terms of high or low art, and what deserves to be heard.”

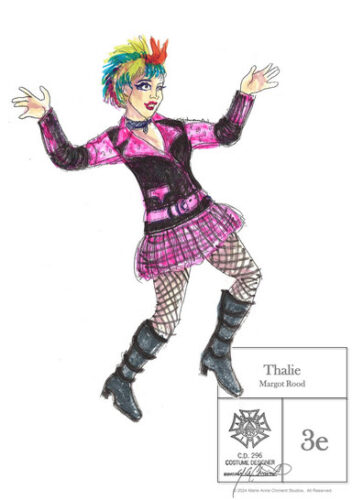

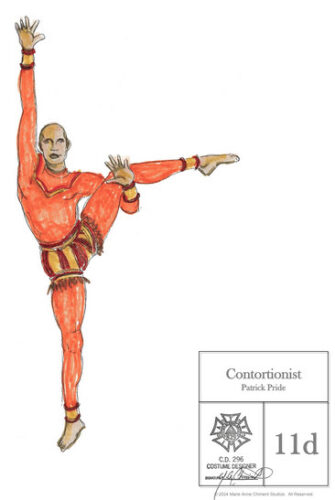

Brown says Opera Lafayette often tries to give “a contemporary angle or contemporary inquiries” to its productions. Don’t expect any knee-length silk pantaloons and ruffled cravats. The visual focus of Marie Anne Chiment’s costumes will remain in the modern day. “It was a very cutting-edge opera at the time,” says Turocy, “and it says in the documents that the performers are supposed to be in contemporary dress.” She describes Chiment’s designs as being from “various decades, but definitely the 20th century.”

Between the Prologue and the Critique there are three acts: “La Fille” (The Girl), “La Veuve Coquette” (The Coquettish Widow), and “La Femme” (The Wife). “In each of the stories,” says Brown, “the women sort of get the better of the men. They’re funny stories about love.”

Or perhaps about not caring about love, Turocy suggests. “Léandre, in the first act, really enjoys being not enchained by love. She keeps saying, ‘I’d just rather play my guitar and sing and dance.’ But her fate is assumed: She’s going to get married.”

The widow in Act 2 is just as uninterested in finding a new husband. She has suitors, but they don’t capture her heart. “In the end, she just leaves the stage and says, ‘I don’t really want either one of you,’” says Turocy. Against convention, Mouret and his librettist, Joseph de la Font, end the act with the two rejected men alone on the stage. “There’s no big finale. There’s no big dance number. That’s it.”

The action picks up in Act 3, set at a costume ball. “It’s like the ball nights in Venetian carnival season,” Turocy says. But again, love is pushed aside. “As soon as you’re about to see the two lovers kiss, Thalie breaks in and says, ‘I’m great, and everything is wonderful.’” The audience gets yanked out of the romance and reminded about the meta-argument over whether comedy is worthy of a stage.

Typical of French Baroque operas, dance is essential in Thalie. Turocy, a choreographer, is the founder of the New York Baroque Dance Company. Although she has choreographed Opera Lafayette productions in the past, this time she’s in the director’s chair. A team of dance-makers is working with her: Julia Bengtsson and Julian Donahue for Act 1; Anuradha Nehru for Act 2; and Caroline Copeland, associate director of NYBD Co., choreographing Act 3 and the finale.

Expect a wide range of styles. “You’re going to see pointe shoes,” says Turocy. “You’re going to see contortion. You’ll see somebody playing a mechanical doll.” She also promises “something like clog dancing and someone doing some kind of fake Spanish dancing.” During a wedding scene in Act 2, the Kalanidhi Dance Company will be featured. “They do South Indian and Kuchipudi work,” says Brown, who has worked with them twice before. “It has similarities to Baroque dance and pantomime, and it’s a really ancient tradition.” The 20th century will be represented in dance, too. In the party in Act 3, says Turocy, “we’re doing something from the Hustle, maybe mixed a little bit with the Stroll.”

Despite modern costumes and dance, the music itself will be played on period instruments. Turocy sees no cognitive dissonance between historically informed music-making and modernized aspects. “I can recognize tropes in the music, so when I’m putting it into a modern style, it’s just that it’s being translated to today’s feelings.” Still, the music is paramount. “The music and the text are the evidence of what it was like,” she says, “and the emotions and the dramatic landscape of the whole piece has to go along with the music.”

To present that “evidence,” Brown tapped Baroque specialist Christophe Rousset, founder of celebrated French ensemble Les Talens Lyriques. It will be Rousset’s conducting debut with Lafayette, although in October he joined members of their orchestra and bass Jonathan Woody, who is also in the Thalie cast, for a recital of music by François Couperin.

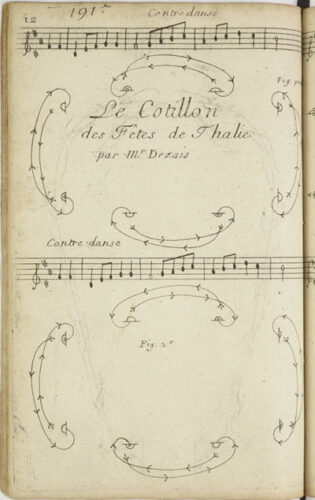

Assisting Rousset and playing continuo in the opera will be Korneel Bernolet, who had another essential task: making the first modern edition of the music. He worked with several sources, says Brown. “There are different scores, from both 1714 and 1720. We’re basically doing the 1720 version. But those are short scores, and they don’t have all the orchestral parts.” They used orchestral parts from a 1750s revival to help guide their work.

Harris-Warrick proofread Bernolet’s edition. Instrumentation was a big factor. “There were certain conventions,” she said of works written for the Paris Opera. “When you’re doing a pastoral scene, you’re going to bring on the oboes, and if you’re doing a ceremony, you’re going to bring on the flutes. For military scenes you had trumpets and drums.”

The presence of non-Baroque and non-European elements enhances the opera, Brown believes: “The trick I find when staging old stuff is figuring out how to be true to each musical gesture and each phrase of the libretto, yet still making it possible for people today who might not know this music to find a way in.”

The best HIP efforts notwithstanding, the music will not sound quite as it did at the Paris Opera in 1714 because of the cost. “Paris had an orchestra of roughly 50 players,” says Harris-Warrick. The Lafayette performances will have closer to 20. Nor will there be a separate chorus; instead, the soloists, each of whom will take on multiple roles, will also sing the choruses. And Lafayette will use only seven or eight dancers. (Originally there were about 40!)

Such financially based compromises are normal for any company putting on a Baroque opera today, and creating productions like Thalie is the reason Opera Lafayette exists. After 2024-25, the company’s 30th season, Brown is stepping down as artistic director. His successor, Patrick Duprey Quigley, has offered a project from his native New Orleans: a never-performed French grand opera called Morgain by Edward Dédé, born in 1827, a first-generation freed person of color.

Opera Lafayette will give the modern premiere next year in collaboration with New Orleans’ Opera Creole. Brown suspects that Quigley “will continue our effort to bring historical works to life and make them relevant to us in the 21st century.”

Sounds like some serious fun.

Anne E. Johnson is a freelance writer based in New York. Her arts journalism has appeared in the New York Times, Classical Voice North America, Chicago On the Aisle, and PS Audio’s Copper Magazine. She teaches music theory and ear training at the Irish Arts Center in Manhattan. For EMA, she recently wrote about the West African kora on the early music landscape.