by Mark Kroll

Published June 17, 2024

Printing Music in Renaissance Rome by Jane A. Bernstein. Oxford University Press, 2023. 272 pages.

Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press and moveable type, in the middle of the 15th century, not only made the Bible and other religious texts available to a wide readership, but set in motion a revolution in music printing that changed the course of music history. Not surprisingly, Renaissance Italy led the way for this revolution, as it did for so many creative activities in the humanities and the arts.

In 2001, Jane A. Bernstein’s award-winning study of Venetian music publishing, Print Culture and Music in Sixteenth-Century Venice, revealed the invaluable contributions of Ottaviano Petrucci and his fellow music printers and publishers. In her latest book, Printing Music in Renaissance Rome, she has turned her formidable scholarly attention to Rome, another hub of music publishing during this period. Her book is full of details about how and why music was published in Rome, and subsequently placed in the hands of those who would translate those symbols into sound.

In the introduction, Bernstein tells us that not only did Rome rank “second only to Venice as an important center for music book production in Cinquecento Italy,” but “Romans’ ingenuity and willingness to meet individual clients’ needs” resulted in music editions in a broader array of shapes and sizes (from small octavos to large folios and broadsheet choir books) as well as a “wider range of printing techniques” than those found in La Serenissima (i.e., the Venetian Republic).

Indeed, after realizing that “some of the books were of a monumental size that I had never seen in Venetian editions,” Bernstein initially worried, with mock alarm, that she might have to move to a larger house (or at least one with bigger bookcases). Rome also “became the site of several notable milestones in the history of music printing,” the innovative technologies and techniques that publishers developed closely reflecting the musical repertory that satisfied the liturgical goals and “economic and social climate” in the Eternal City.

The author begins her study with the first dated and the earliest known music book from Rome, the Missale Romanum of 1476, printed with moveable type “only twenty years after Gutenberg’s invention” by the German-born Ulrich Han, who described his background, intentions, and goals in the colophon at the back, and in so doing summarized the beginnings of Roman music printing: “This sacred and most holy work Ulrich Han, a German from Ingolstadt, citizen of Vienna, left for posterity to the honor and glory of Almighty God, not by pen nor by copper burin but cast and printed at Rome by a new kind of art and ingenious labor, together with music, which was never done.” As Bernstein suggests, Han might be considered Rome’s Petrucci.

We subsequently follow the careers of Han’s successors in the music publishing and printing business in Rome, and their innovations, including technical details about paper size, typefaces, and formats. This information is presented in exhaustive detail that can sometimes be daunting, but still well worth the effort. For example, we learn that paper came in a variety of dimensions, weights, hues, and textures, and that by the end of the 14th century, “the four sizes — imperialle (74 x 50 cm), realle (61.5 x 44.5 cm), mezzana (51.5 x 34.5 cm), and rezute (45 x 31.5 cm) — had become standard for papermaking in Italy. Even larger-size paper, carta papale (84 x 55 cm), was used by the Curia, mainly for deluxe manuscripts, while rezute, “the smallest and cheapest” became “the most common paper used for sixteenth-century music books.”

However, this book is not just a study of materials, fonts, and mechanical techniques, but also about the “customers” for these products — the musicians — and the “synergistic relationship” between the production of music books and the various musical genres in the Eternal City. Some of the most famous names in music history are invoked, such as Orlando di Lasso, Jacques Arcadelt, Cipriano de Rore, Tomas Luis de Victoria, Giovanni Palestrina, Luca Marenzio, and Emilio de’ Cavalieri.

Here we learn much about the music and performance practices in Rome during this era, as well as a few bits of juicy gossip, such as the fact that Palestrina’s meteoric rise to fame at the Sistine Chapel was cut short only eight months after entering the Capella Sistina, sending his career “into a tailspin,” when Pope Paul IV enforced the rule of celibacy for all members of the Chapel, meaning that the married Palestrina was forced to vacate his position.

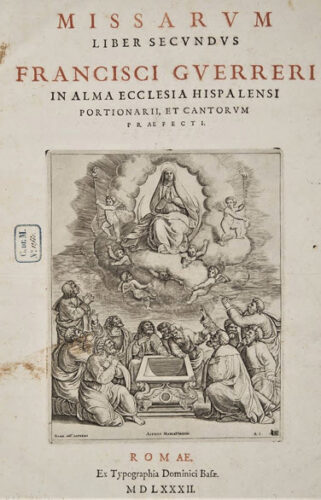

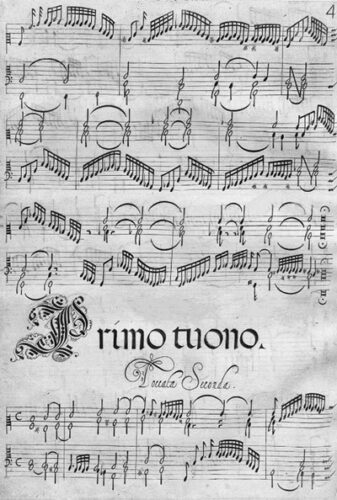

Marenzio’s success as a prolific composer of secular madrigals in sacred Rome is also examined, as is Cavalieri’s innovative and ground-breaking Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo of 1699, the first large-scale vocal work issued in full score from movable type, and the very first publication to include a continuo with precise indications for figures and accidentals. Bernstein comments on the role of Tomas Luis de Victoris in creating a “Spanish market” for Roman publications, and describes how Luzzasco Luzzaschi’s Madrigale…per cantare et sonare a uno, e doi, e tre soprani (Rome, 1601) illustrates the way copperplate engraving facilitated the reproduction of highly ornamented melodies.

Bernstein tells a vivid story of the rich and varied array of books published in the Eternal City that not only placed Rome at the technological forefront of the printing world, but in fact reflected a greater diversity of musical expression than the volumes printed contemporaneously in Venice. Her study should also serve as a useful reminder to those of us today who can so easily find music of almost every style, era, or instrumentation in most libraries, directly from the publishers, or accessed at that wonderful online resource, IMSLP, the International Music Score Library Project (appropriately also known as the Petrucci Music Library): We owe a debt of gratitude to Petrucci, Han, and all of their colleagues in the early years of music printing.

Mark Kroll has served as the book review editor of Early Music America for the past 25 years. He recently performed a recital with Baroque violinist Carol Lieberman in Sarasota, Fla., returned a few months later to play the Frank Martin Harpsichord Concerto (1951-1952) with the Sarasota Ballet, and is currently writing a book on contemporary harpsichord music.