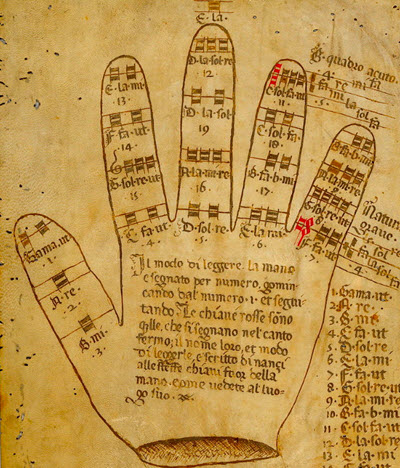

“There is no more dreadful insult with which to charge a musician than the claim that he does not know his hand,” wrote Johannes Tinctoris in 1472, referring to the Guidonian Hand, a centuries-old music-reading tool.

Thomas Morley’s 1597 Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke opens with a dialogue between two students. One has just embarrassed himself at a dinner party when part-books were passed around and he had to admit shamefully that he couldn’t read music, causing other guests to wonder how he had been brought up.

Somewhat more recently, I have found that students are often preoccupied with ornamentation and cadenzas, or which note begins a trill, when it’s actually their basic musicianship skills that could save them from insult, shame, and embarrassment.

Staff Sergeant Peter Walker, singer and multi-instrumentalist, insists that sight-reading skills have helped his career. “It’s an even more useful tool than being well-versed in stylistic nuances.” But what about students obsessed with whether to begin a trill on the main note or the upper auxiliary? “Well,” he laughs, “to begin your trill on the main note, you’ve got to be singing the right note first!”

Singer and musicologist Hannah McGinty weighs in: “I find it extremely annoying to work with singers who can’t sight-read. It’s essential — right up there with being a good colleague and being easy to work with.” She adds that, as a choral director, “I would [hire] someone like an organist with a nice voice and excellent sight-singing skills over an opera singer who can’t read.”

Tenor Paul Elliott also finds that good sight-singing “saves time and shows that you can hear the sounds the music notation is showing you.” Coming from the British choral tradition, he also expects sight-reading to go further, “to allow a reasonable interpretation on the fly, leading to more productive rehearsals.”

If even an Elizabethan-era dinner party guest was expected to be able to read at sight (and for fun!), what level of skill did professionals exhibit, and how did one acquire these skills? Solmization, which used the note-names and modulating hexachords on Guido’s hand, was taught, written about, and used extensively well into the 19th century, as documented by Nicholas Baragwanath in The Solfeggio Tradition. [Reviewed by EMA last year.] Morley advises his embarrassed pupil that to learn intervals, one should imagine the notes in between them, a very old and widespread technique.

Sight-reading, clef-reading for transposition, rehearsing, and memorizing are interconnected. Cornetto player Bruce Dickey reminds us that Dario Castello, in the preface to his sonatas — which Dickey himself finds “very demanding” — suggests reading through them once before playing in public. “This tells me both that the players were very good sight-readers, and that it was common to play such pieces without any rehearsal.”

Similarly, Claudio Monteverdi advises rehearsing his balletto Tirsi e Clori, which lasts about 12 minutes, for an hour before performing it. According to performer-scholar Loren Ludwig, the singers of the Sistine Chapel would read over new music together to be sure there were no errors. That way, if one of them messed up in performance, they couldn’t blame a faulty part to escape the fine for singing a wrong note.

No one is born knowing how to sight-read. Practice plays a big part in improving the skill. Multi-instrumentalist and singer Debra Nagy finds her sight-singing skills weaker than her instrumental sight-reading, which may just be a function of doing it less regularly. She adds, “One of my secret musicianship powers that I wish other instrumentalists felt more comfortable with is transposition and clef-reading. Why can’t everyone read C clefs?” Having learned alto clef in a one-semester viol class, she continues to find it useful for score-reading and transposing in particular.

Harpist and director Andrew Lawrence-King notes that “young performers might get their first big gig jumping in for a sick colleague.” With people he hires, he finds “good sight-reading isn’t necessarily about getting to the concert faster, it’s about starting rehearsals at a higher standard.” But Lawrence-King also recalls being “in rehearsal with Jordi Savall and many amazing Cuban musicians, not all of whom read at all, but who learn stuff faster than some of the slower Mediterranean readers.”

We don’t talk enough about the connections between basic musical skills like sight-reading, clef-reading, ensemble skills, and memorization. Is there more to this story? Write to me!

Mezzo-soprano Judith Malafronte teaches in the Historical Performance department of Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music and writes for arts publications nationwide.