In NAGAMO, composer Andrew Balfour reimagines history and the concept of respect and dialogue between nations of the so-called New and Old World

Charting a course for settler ensembles to collaborate with Indigenous artists

This article was first published in the May, 2024 issue of EMAg, the Magazine of Early Music America

By Jacob Gramit

This article deals with the distressing history of Indian Residential Schools in Canada and Native American Boarding Schools in the United States. If you need support in Canada, the National Indian Residential School Crisis Line provides 24-hour crisis support to former Indian Residential School students and their families toll-free at 1-866-925-4419. In the U.S., you can find resources through the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition: boardingschoolhealing.org.

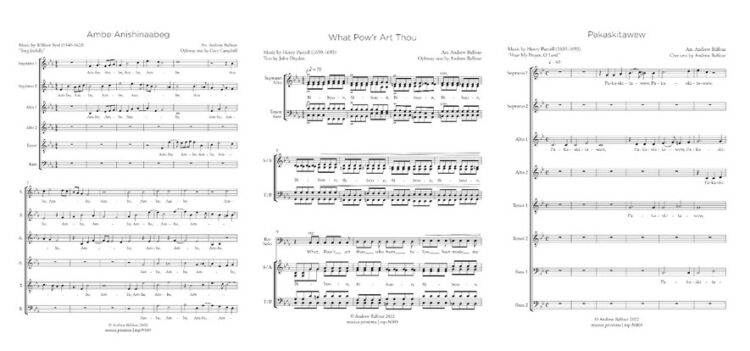

As of May 2024, Cree composer Andrew Balfour’s NAGAMO is two years old. His 45-minute, a cappella choral work — a “curation” of original compositions and arrangements of Renaissance gems — is scored for choirs of all abilities.

Since its premiere in 2022, NAGAMO — “SINGS” in the Ojibway language — has traveled across Canada, been performed in residence at universities and with youth choirs, and was recorded in 2022 alongside a documentary about the project. The sheet music has been sold across Turtle Island (North America), and plans are underway for more touring, both regional and international. The project has been a success for Balfour and for musica intima, a vocal ensemble based in the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh nations — the Coast Salish peoples — on land we now call Vancouver. As a baritone with musica intima, I also serve as the group’s artistic manager.

In the story that follows, we’ll explore the genesis of NAGAMO and why it’s so important to us. We’ll also share a few of the lessons we learned from this collaboration of Indigenous and settler arts.

Balfour is a visionary musician living in Tkaronto (Toronto). He’s a composer, conductor, singer, and sound designer with a large body of choral, instrumental, electro-acoustic, and orchestral works. His music has been commissioned far and wide, from Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra and the Toronto Symphony to Roomful of Teeth, a trend-setting choral group from New York.

Balfour is also the founder and artistic director of the innovative vocal group Dead of Winter (formerly Camerata Nova), performing in the Treaty 1 territories of the Ojibway, Cree, and Dene people in what’s now called Winnipeg. Dead of Winter specializes in creating “concept concerts,” many with Indigenous subject matter: Wa Wa Tey Wak (“Northern Lights”), Medieval Inuit, and, most recently, Captive. These complex offerings explore a theme through an eclectic array of music, including new composition, arrangements, and inter-genre and interdisciplinary collaborations.

In a 2019 profile, The Globe and Mail wrote of Balfour’s “works that range from shimmering soundscapes to unsettling sociopolitical commentary. One of his most arresting works, Take the Indian, features snippets of testimony from hearings conducted by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: ‘They took away my heritage, they talked of paradise with a whip, they came to me at night.’”

Born in 1967 to a mother from the Fisher River Cree Nation, Balfour became part of what’s called the “Sixties Scoop” — the mass removal of Indigenous children from their families, put into the Canadian foster-care system, where conditions ranged from caring settler families to abuse that was comparable to slavery. At six weeks old, Balfour was taken from his people and adopted by a white Winnipeg family, whom he describes as “loving and supportive.” They had musical interests: His mother was a violinist and his father, a church minister, helped immerse him in Anglican choral music.

Even under the best circumstances, however, the “Sixties Scoop” generation (1960-1980) too often struggled with mental health problems, addiction, poverty, homelessness, and, in Balfour’s case — what he terms “lost years” — dropping out of college, substance abuse, and prison.

Soon after his four-month sentence ended, and just after he began connecting with his Indigenous identity, he began singing Renaissance choral music — the repertoire he knew as a child chorister — with an informal group that later became Camerata Nova. And he started composing short works for the group to perform.

Andrew Balfour: I was colonized as a very young child — taken away from my blood, and taken away from my language and my medicines, and this identity. So I’ve been searching through that as a composer, and I feel that it’s still a lifelong journey. I’m lucky enough to be able to work with incredible musicians, and artists, and groups, and I think finally there’s an understanding, at least from what I can see in the choral world, of what it really means to listen, what it really means to follow protocols and have the respect towards something very different; that’s important for a step towards what we call reconciliation.

First used by official investigations of human rights abuses in Chile and South Africa, the now-familiar term “Truth and Reconciliation” was revived by the Canadian government for its own commission (TRC): “Truth” being that public policy was designed specifically to eradicate the culture of Indigenous peoples — many of those racist policies are still in place today — and “Reconciliation” being how the government and citizens fix and reckon with that.

Although the focus of the TRC was primarily on the Indian Residential Schools, it encompassed the entire history of systemic racism and oppressive policy, including forced adoptions, land theft, and more. We have a Canadian lens, but these assimilation policies were not unique. The American Indian Boarding Schools, as early as the 17th century and concentrated in the late 19th and 20th centuries, were equally abusive, disease-ridden, and church- and government-funded. While there has not yet been a commission in the U.S., hundreds of thousands of Native children were taken from their families to attend the more than 523 such schools across the country, which began closing only in the 1980s and ’90s. While the policies surrounding these schools have shifted, 125 remain open today.

The Canadian TRC released 94 “Calls to Action” in 2015, which covered everything from encouraging more radio programming in Indigenous languages, to asking for official apologies from the church institutions that ran the Residential Schools, to demanding a search for the bodies of (at least) 6,000 children who died anonymously and were buried in unmarked mass graves while attending the schools. Call No. 83 reads: “We call upon the Canada Council for the Arts to establish, as a funding priority, a strategy for Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists to undertake collaborative projects and produce works that contribute to the reconciliation process.”

It’s long past the time to decolonize our approach to the choral arts. We prioritize Indigenous voices and cede our artistic control to our collaborators.

For musica intima, we read this as a direct call to pursue such collaborations. As a society it’s long past the time to decolonize our approach to the choral arts. Thus musica intima has shifted toward more collaborative endeavors. We prioritize Indigenous voices and cede our artistic control to our collaborators. Which brings us back to NAGAMO.

NAGAMO premiere in Vancouver

Balfour: For many years I’ve been thinking about this idea of approaching Renaissance music from an Indigenous lens or transcribing the texts into Indigenous languages. I didn’t really pitch [musica intima] as much as I just said, ‘One day I’d like to do this.’ And I think that’s how ideas come to fruition.

The musica intima singers had workshopped and performed a few of Balfour’s pieces in COVID-era digital offerings. He’d been interested to translate the Byrd Cantiones sacrae into Indigenous languages. Since early music is a pillar of musica intima’s repertoire, this English Renaissance and new-music project, which became NAGAMO, seemed a perfect fit. What followed was Balfour’s carefully thought-out, 700-word plan.

This was going to be a ground-breaking project, and, more than that, we were just along for the ride.

Immediately we realized that something bigger was in motion: This was going to be a ground-breaking project, and, more than that, we were just along for the ride. Balfour’s precis came from a broad worldview:

Balfour: NAGAMO reimagines history and the concept of nation-to-nation respect and musical dialogue between the nations of the so-called New World and Old World. During the beginning of the seventeenth century, several Chiefs and esteemed Indigenous leaders journeyed to Europe in the hope of forging alliances. In many cases, they were treated as respected ambassadors. History shows that, although there was a hopeful beginning between the Europeans and the Nations of Turtle Island, the relationship turned disastrous for the Indigenous nations and peoples from colonizing, disease, war, genocide, and such. NAGAMO explores a reimagining of history and the fantastical idea of what might have happened if the sharing of music and respect of culture had succeeded, and how a different history might have played out if this had happened.

Based on the power of Balfour’s program, musica intima sought funding and set up a cross-country tour with youth and university choirs — all before we sang a single note. Balfour then focused on writing the actual music.

Balfour: I found it very gratifying: one, as a composer and two, as an early-music person. I appreciated the polyphony, and I appreciated what those composers were doing with their Latin or English texts, but also at the same time I was really excited because I was changing the identity of these pieces. I was totally appropriating this music, and that was exciting as well. I wanted to get out of that Eurocentric imperialistic lens, or acts of superiority. I wanted to have not translated the Christian texts, but actually to bring an Indigenous lens, and Indigenous ideas of medicines and spirituality, and appreciation for Mother Earth; I thought that was very important. And as a result, while I was working through the scores, a lot of the time, the text, whether it was Ojibway or Cree, felt perfectly in place with the polyphony.

In the end, we performed five new texts by Balfour to Renaissance pieces, plus two of his own, alongside a handful of unaltered works by Tallis, Byrd, and Ferrabosco. The Vancouver premiere took on its own collaborative life. Since Balfour was coming to lands that were not his — the Cree nation is historically based in the central prairies of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba — the composer wanted to ensure that the voices of those who had been stewarding the lands of the West Coast were also heard and honored. We commissioned Kwakwaka’wakw artist Sonny Assu (based on Vancouver Island) to design art inspired by the performance. Through a series of connections with the local community, we met singers and drummers of the lexwst’í:lem drum group, who joined us in the performance.

Balfour: Meeting the lexwst’í:lem drum group and Nicole Bird, who runs that ensemble, really brought poignancy to this. I’ve worked with a lot of song keepers, and drummers, and pow-wow groups, but they were unique, they were so sensitive. Many of them are Residential School survivors, and they’ve seen a lot, and way more than I can possibly imagine, some of their wounds, and trauma, and upbringing. So to see them with their regalia, and hear their voices and their drums and their movement — it brought me to tears in a good way, realizing this is the power of music, but this is also the power of reconciliation. The only way these wounds are going to be healed is with understanding, and love, and respect. I felt the energy in the audience at the concert was important, to see that people were really listening and really respecting these people, and the weaving of the Elizabethan music with the Indigeneity was beautiful.

The concert had a huge impact on audience and singers alike, and permanently altered the trajectory of musica intima. While our artistic practice will always be rooted in the act of communal singing, we have a strong desire to center other voices — through our guest curators, through the design of our performances, and through our repertoire.

Within the ensemble, singer Katherine Evans described the NAGAMO experience: “One of the things that I appreciated most about this project, and about working with Andrew, was how he chose these very short texts, in Ojibway and Cree, that had a different specific meaning than the text of the original, but that the universal meaning was really the same.”

Balfour: I’ve really appreciated the trust placed in me, and I think that’s important in the collaboration. But also providing a safe and respectful environment to be able to work. If you dig deep down, it can be a complex and sometimes traumatic experience, as an Indigenous person, to work with non-Indigenous people. I felt I made new friends. Indigenous languages such as Ojibway or Cree have many meanings to them, so that was really important putting them with the music. My heart is full of joy and hope, and my body feels the vibrations of what I’ve just experienced.

At musica intima, we know we’ve made mistakes along the way, and we will make many more. Any collaboration with folks with different lived experiences presents artistic risk. There’s audience risk as well: Your patrons may be more close-minded than you think, although they may be surprisingly open-minded as well. Andrew Balfour speaks of Truth and Reconciliation not as a destination, but as a journey: many Indigenous folks believe that it will take seven generations to heal the trauma of the Residential and Boarding School systems.

Seven generations of healing

The work is only beginning. But as a settler ensemble, musica intima has found a few keys to success:

- Take your time. These projects should never start with a deadline or deliverables. Open with a conversation about how you like to work or what you’re striving for. And even after you set dates, leave room both in timeline and budget for the project to evolve, perhaps involving new collaborators or a shift in scope.

- Open the doors. Allow your collaborator into the rehearsal room as much as possible to make direct connections with the artists and ensemble. In a traditional artistic-director model, it’s easy to see the logistical advantages of talking to your collaborator and then disseminating those observations to your ensemble. But the actual relationships that can be formed between performers and creators will create a stronger product and a lasting relationship. The other side of this: Let your audience or community into the rehearsal space as well. It’s crucial that we all witness this work taking place, to learn and grow from the ideas that other organizations have.

- Land acknowledgements. These are increasingly common across the U.S. and expected by funders in Canada. Performers should acknowledge the colonial history that took this land from Indigenous nations, either by naming the treaty that was negotiated, or, as on the West Coast, using the word “unceded” to describe land that is not governed by a treaty, where settlers stole the land. This is a first step. Online resources such as www.whose.land/en will tell you on whose land you reside. Then you can begin to move forward on the journey of “Truth and Reconciliation.”

- Go beyond. Just putting a land acknowledgement in your program booklet is not enough. Everyone in the room needs the opportunity to reflect on the simple facts of stolen land, so it should be spoken from the stage. (And please avoid the trap of squeezing it between “turn off your phones” and “tonight is sponsored by…”) Inviting local elders or knowledge keepers is a way to go beyond your own land acknowledgement, but be sure you research proper protocol and compensation for any guests.

Combined, these four little ideas leave an incredible opportunity for a radical reimagining of artistic output.

Music, of course, is only the beginning. This project opened space for collaboration with dancers, visual artists, and filmmakers, and as we look toward seven generations of healing and prepare for our NAGAMO tours this year, we prioritize working with youth ensembles.

By focusing our intentions outside the room, we start to experience more than our own ideas, our own programming, our own collaboration. By giving away some of that artistic control, projects that shake the core of how we believe art should be created can grow and thrive.

Jacob Gramit, from Treaty 6 territory, the traditional lands of First Nations and Métis peoples, is a Vancouver-based settler baritone, specializing in the music of the Baroque and Renaissance. After early-music studies at the Koninklijke Conservatorium in the Netherlands, he returned to the stolen lands of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations, and to musica intima. A version of this article was originally presented at the 2023 EMA Summit in Boston.