by Jacob Jahiel

Published August 31, 2024

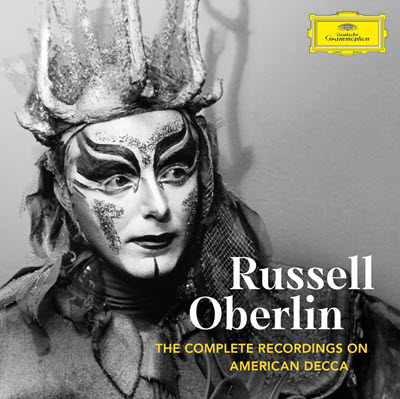

Russell Oberlin: The Complete Recordings on American Decca. Countertenor Russell Oberlin, New York Pro Musica, and others. Deutsche Grammophon 486 4034

Remember when early music was regularly broadcast on national television? If not, you would be forgiven; it’s been over six decades since the phenom Russell Oberlin, credited as the first American countertenor to gain international renown, joined classical celebrities like Glenn Gould and Leonard Bernstein by appearing in telecasts viewed across North America. Admired for his evenness of range and captivating tone, Oberlin was, quite simply, nothing short of a sensation.

Deutsche Grammophon has reminded us why with a newly remastered, nine-disk set, Russell Oberlin: Complete Recordings on American Decca. It’s a large collection spanning medieval monophony to madrigals, from Handel arias to music by William Walton. The recordings feature ur-historical performers of now legendary status, such as Noah Greenberg, who first convinced Oberlin to explore his countertenor range and enlisted him in New York Pro Musica.

Sure — let’s get this out of the way — there is much of what you might expect from late 1950s and early ’60s recordings: overzealous vibrato, dramatic vocal scoops, weird diction, excessive instrumentation, and more than a few overwrought interpretations by vocalists and instrumentalists alike, at least by today’s standards. There is no getting around it: these performances can sound dated. But listen closer, and they are also intensely, startlingly beautiful.

Oberlin’s countertenor is stunning. Listeners might begin with the Handel arias disc (CD 5) to gain a baseline understanding of all he is capable of. Immediately evident in the Messiah tracks are the incredible purity of his voice, his breathtaking ability to weave a long melodic line, and a sensitivity for larger architecture and phrase that I wish more performers possessed today. He conjures rare pathos in “Ah dolce nome” from Muzio Scevola, and Rodelinda’s “Vivi tiranno” foregrounds a truly breathtaking vocal agility. (For more on early reactions to his singing, as well as a treasure trove of information on this performer’s fascinating history, see the collection’s liner notes by EMA’s publications director, Pierre Ruhe.)

Much fun is to be found in the earlier repertoire, too, even if it’s here where those aforementioned idiosyncrasies are most apparent. CD 1 (Music of the Medieval Court and Countryside and, I might add, a fair amount of Renaissance music), features a rendition of “Ríu Ríu Chíu” that surpasses even the seminal Monkees version, as well as an intensely soulful Salve Regina by Martín de Rivaflecha, a Renaissance composer new to me. The instrumental music is imaginatively conceived.

CD 2, The Play of Daniel (A Twelfth Century Musical Drama) serves as a reminder of the meteoric success generated from a series of performances that catapulted Oberlin and New York Pro Musica to the forefront of not only the early-music scene, but the cultural eye of New York writ large. The initial set of performances, beginning in January, 1958, garnered overwhelming critical acclaim, and soon ticket requests exceeded hall capacities four times over. This led to a recording contract with Decca, live performances as far abroad as Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, and eventually a televised version produced by National Education Television.

CDs 3 (Sacred Music of Thomas Tallis), 4 (Elizabethan and Jacobean Ayres, Madrigals and Dances), and 7 (Josquin des Préz: Missa pange lingua [Motets & Instrumental Pieces]) offer an impressive array of Renaissance polyphony, energetic and well-paced, plus a host of imaginatively rendered instrumental works. They contain a palpable verve full of raw, infectious enthusiasm — uncareful (mostly in a good way) renditions of music by Tallis, Byrd, and Dowland, among others, as well as a refreshingly full-throated, soulful Missa Pange lingua.

Outside the immediate realm of early music but nonetheless noteworthy: Oberlin’s spectacularly expressive renditions of Schumann and Wolf songs in CD 8 (A Russell Oberlin Recital) rival those of Peter Pears. For a masterclass in recitation, as well as a taste of Oberlin’s terrific sense of humor, look to his rendition of William Walton’s Façade — An Entertainment for Reciter and Chamber Orchestra in CD 9.

This collection may not ever be the first I turn to when hankering to hear, say, Josquin, Tallis, or Handel. But they are undoubtedly among the most memorable I have yet encountered — for a few bad reasons, but for infinitely more good ones. More than a mere historical curiosity, or a quaint reminder of how far we have come in the realm of historical performance, these are recordings of enduring artistic value.

Jacob Jahiel is a writer and viola da gamba player living in Baltimore.