by Anya B. Wilkening

Published September 15, 2024

The Media of Secular Music in the Medieval and Early Modern Period (1100-1650). Vincenzo Borghetti and Alexandros Maria Hatzikiriakos, eds. Routledge, 2024. 319 pages.

Most of us are now constantly bombarded by content, with updates on current events, the social lives of our friends, or the latest and greatest product delivered directly to us via our phones and inboxes. One might be forgiven, then, for seeing the word “media” in the title of this book — The Media of Secular Music in the Medieval and Early Modern Period (1100-1650) — and not immediately understanding its scope. Editors Vincenzo Borghetti and Alexandros Maria Hatzikiriakos conceive of the term broadly, yet each author in this collection of essays offers new perspectives and approaches.

“Each chapter,” write the editors, “considers the objects it analyses as complex channels or systems of communication, as publications, or, more generally, as phenomena…Such complexity derives from the elements and material aspects of the sources, from the means or modes they use, from the user/reader response they elicit, and vice versa.” This collection contributes to the growing body of literature on the materiality of music sources (exemplified, for instance, by Kate Van Orden’s Materialities: Books, Readers, and the Chanson in Sixteenth-Century Europe, or the collection of essays Early Printed Music and Material Culture in Central and Western Europe, among many others), though with a wider, more diverse lens.

The objects that are explored are varied indeed. They include “conventional” musical sources: Davide Daolmi, for example, opens the volume by examining the musical notation of the Codex Buranus. Other authors show how less traditional types of media may be mined for musical information, as Tim Shephard’s discussion of 16th-century household objects capably demonstrates.

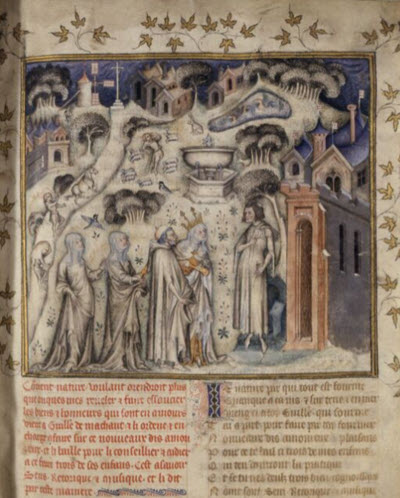

Even when the primary function of an object is ostensibly musical, scholars approach it from creative material perspectives: Though Jane Alden focuses on the Loire Valley Chansonniers, it is their construction — their layout, decoration, and especially their size — that she uses to illuminate aspects of the manuscripts’ musical culture and community. Similarly, Anne Stone examines the effect of the mise-en-page of Machaut’s so-called “Prologue” as it is transmitted in MS Paris, BnF, Fr. 1584. The visual and tactile effect of the Prologue’s layout, she argues, primes readers to engage with the subsequent visual, textual, and musical content in a particular manner.

This expansiveness also extends to the authors’ understanding of music (which includes, as the editors write, other “sonic phenomena”). The porous boundaries between sacred and secular are also usefully interrogated throughout. Klaus Pietschmann, for instance, explores the appearance of secular musical practices in hagiographies. The temporal scope is similarly broad, and the collection thus includes both printed media and manuscripts, and addresses repertoire from monophonic song to polyphonic instrumental works.

The geographic range is, however, limited to Western Europe; a single chapter by Alexandros Maria Hatzikiriakos on a 16th-century Greek romance represents the only excursion outside the traditional historiographic borders.

Perhaps because of this breadth, the editors have organized the volume by theme, dividing the articles into four sections based primarily on the type of object under discussion. The first two sections, “The Materiality of Song” and “Songs, Books, and Society,” are complementary, as authors in both focus on music books (including song books, both real and imagined, textbooks, and even modern editions).

Essays in the first part focus primarily on single sources, addressing how their physical components work in concert with their contents to create meaning for readers. The second section examine the same types of objects but situate them within their larger cultural context. The authors consider what these sources tell us about their reading communities, providing insight into the people that produced and used these books and the societies in which they circulated.

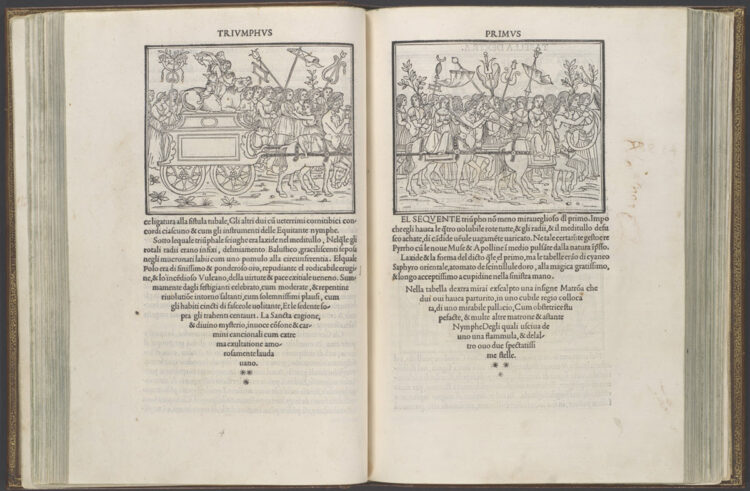

The third and fourth sections turn, respectively, to images and musical objects. In both parts, information about sound and music come from unlikely sources: pictures of music making in otherwise non-musical texts (as in Massimo Privitera’s chapter on the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili) or liturgical manuscripts repurposed in accounting book bindings (as discussed by Matteo Nanni). This organization invites the reader to make interesting connections across the sections and between objects and repertoires that are not typically considered in proximity to one another. The interweaving of music, material object, and aristocratic identity, for instance, is a recurrent theme across the volume (addressed by Franco Piperno, Yolanda Plumley, and Shephard), while both Stone and Privitera explore the ways texts can orient their readers towards music and sound.

The reader’s engagement with the object is, of course, entirely mediated by the author; as with other texts on materiality, this is a persistent challenge. Descriptions of manuscripts are aided by images and diagrams, but nevertheless are not always entirely clear. References to pigments in text or decoration, for instance, fall somewhat flat when accompanied only by black-and-white images.

And while the editors emphasize in the introduction how important digitization is in enabling this type of scholarly work, only one author (Tim Shephard) provides hyperlinks to the objects themselves in the e-book edition. However, these links do not function properly: When opened from the e-book, they send the reader to the home page of the relevant museum, rather than to the specific entry.

These are minor inconveniences, though, which should not take away from the effectiveness of the volume. Collectively, the essays reveal new ways of listening to the past by suggesting approaches to a wide array of media.

Anya B. Wilkening recently completed her Ph.D in Historical Musicology at Columbia University, and currently holds a postdoctoral fellowship from the Belgian American Educational Foundation. Her research focuses on new analytic approaches to musical borrowing in Medieval vernacular song.