by Steven Silverman

Published September 20, 2024

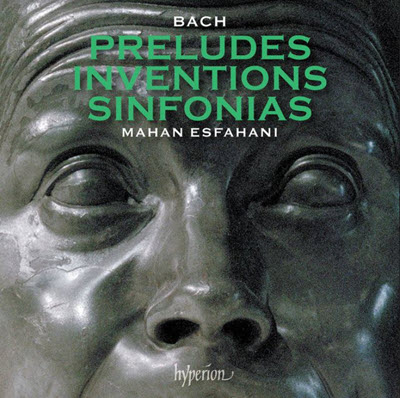

J.S. Bach: Preludes, Inventions, Sinfonias. Mahan Esfahani, clavichord and harpsichord. Hyperion CDA68448

Mahan Esfahani continues his traversal of the keyboard music of J.S. Bach with a recording of the Two-Part Inventions, the Three-Part Sinfonias, and the various small (“kleine”) Preludes. His Bach recordings, on the independent British label Hyperion, now encompass the Partitas, French Suites, Italian Concerto and French Overture, Toccatas, and the Anna Magdalena Notebooks.

The new recording has the same high standards as its predecessors. Esfahani’s ornaments crackle. His passagework is clean and well-phrased — never sounding like sixteenth notes just chugging along. Indeed, some of the faster pieces, such as the C Major and B minor sinfonias, are exuberantly virtuostic. Trills are well-gauged in both character and varied rapidity, never devolving into trills of the dreaded doorbell/alarm clock type.

Most of the pieces on this album were written for teaching purposes. Many of the preludes come from the Clavier-Buchlein for the composer’s son, Wilhelm Friedemann. Similarly, Bach’s preface to the Inventions and Sinfonias (1723) states that goal of these pieces is “to teach clear playing in two and three obbligato parts, good inventions [viz. compositional ideas] and a cantabile manner of playing.”

Given these pieces’ expressly didactic purpose, one might think they would sound dry and etudish. Not in Esfahani’s hands. If anything, his impeccable technical mastery here is surpassed by his musical imagination. An instance is the tiny, one-minute C Major Prelude, BWV 924, which looks like a formulaic harmonic exercise on the page. By carefully varying note durations and adding some rhythmic push and pull, Esfahani brings the piece to life.

In general, the artist consistently sees beyond the bare printed page, using rubato, tempo gradations, articulation, staggering (playing the hands slightly apart), and tasteful added ornamentation, some of which comes from copies made by Bach’s students, so presumably has some measure of the composer’s imprimatur. For the Preludes and Two-Part Inventions, we also get audible dynamics due to the use of a clavichord, which can (and in Esfahani’s hands, does) produce tones of differing loudness and softness, and which can also alter the quality of sound after a note is struck by vibrating on the key surface (bebung), an effect of which Esfahani makes telling use.

Some of these pieces are bona fide masterworks. Best of all is the F minor Sinfonia, an intensely chromatic piece having some of the affect of the “Black Pearl” variation of the Goldberg Variations. Esfahani keeps each of the lines distinct. He adds a schlieffer (filled in third) ornament to the theme which helps to make each entry easy to hear, over holds to add harmonic richness, and gives a sinister bent to the faster rhythmic undercurrent. This is a great reading.

The E-flat Major Sinfonia and E Major Two-Part Invention are also particularly strong pieces. The Sinfonia is a right-hand duet over an arpeggiated left hand accompaniment. Esfahani paces the piece well. He doesn’t allow the florid ornamentation — mostly Bach’s ornaments added to a fair copy of the original score — to get in the way but, rather, uses the ornaments as melodic enhancements, and manages to coax a vocal character out of the harpsichord. The E major Two-Part Invention is a kind of written-out stagger, with the two lines moving in contrary motion one sixteenth note apart. Played literally, it falls into a monkey-see monkey-do kind of imitation. Esfahani avoids this trap with some tasteful tempo manipulations, plus slightly varying where each of the staggered notes falls so as not to sound metronomic. It works.

I did have questions about some of the artist’s interpretive choices. I think the B minor Invention, with its consistent falling slurs, has more pathos in it than Esfahani chooses to bring out. The G minor Sinfonia gets a highly expressive reading, but I missed that it is a sicilienne. (The A major Invention, on the other hand, has the requisite dance-like lilt in spades.) There also are a bunch of cadential hemiolas (meter changing from 3/4 to 3/2) which I failed to hear, such as the D minor Invention (at mm. 16-17) and at the final cadence and E-flat Sinfonia (mm. 10-12 and 27-29).

But these are quibbles and matters of artistic choice. This disc is a worthy addition to Esfahani’s great traversal of Bach’s stupendous keyboard oeuvre. It comes highly recommended.

Steven Silverman is a pianist and harpsichordist whose performances include concerts at Weill Hall in New York City and the Salle Cortot in Paris. He and his wife, the violinist and violist Nina Falk, are co-founders of the Arcovoce Chamber Ensemble, now in its 25th season. For Early Music America, he recently reviewed Matthew Dirst’s Well-Tempered Bach.