by Jeffrey Baxter

Published October 28, 2024

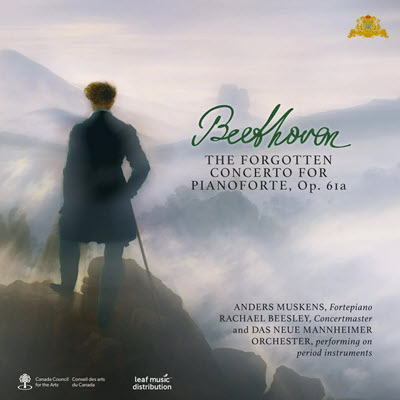

André Campra: Messe de Requiem and Les Maîtres de Notre-Dame de Paris. Ensemble Correspondances led by Sébastien Daucé. Harmonia Mundi HMM902679

In time for the December 2024 re-opening of Paris’ Notre-Dame Cathedral, damaged in a 2009 fire, comes a recording celebrating a noted era in its storied musical history, specifically the years 1640-1700. The liner notes describe the project as focusing “on some of the renowned maîtres who directed the Notre-Dame choir school during this major period and enabled its voices to resound behind the magnificent rood screen (no longer in existence today), thus making their mark on the cathedral’s rich history while also contributing to the decisive developments in music and the elaboration of the ‘French style’ so emblematic of the reign of Louis XIV.”

The Ensemble Correspondances — their name gives a sense of “correlations,” “connections,” or better, “harmonies” — under the skillful direction of Sébastien Daucé, present a finely executed and well-organized collection of sacred music anchored by André Campra’s beloved Requiem. But the most interesting listening on this recording may be from the album’s subtitle: the handful of rarely heard motets, hymns, and mass settings by Campra’s predecessors at Notre-Dame.

Daucé’s performing forces include a chorus of fifteen voices (SATBB: 4-4-3-2-2), an 18-piece orchestra of 12 strings and two flutes (both transverse flutes and recorders) and a continuo complement of bassoon, serpent, archlute, and organ. The assemblage is reminiscent of the Petite Violons, the chamber orchestra of 16 to 18 players that the composer Lully formed in reaction to the bad playing of Louis XIII’s famous 24-piece Grande Bande. (Later, Lully’s Les Vingt-quatre Violons du Roi represented the first organized orchestra with string predominance.)

To begin, conductor Daucé assembles excerpts from François Cosset’s six-voice Missa Domine savum fac regem, framing the two pairs of mass-movements (Kyrie/Gloria and Sanctus/Agnus Dei) with two interpolated motets by Jean Veillot — the impressive eight-voice “Ave verum corpus” and the five-voice “Domine salvum fac regem.” Also included are plainchant hymns composed during this period by Jean Mignon and Pierre Robert.

Cosset’s Missa (one of his eight surviving mass-settings) was composed for a high feast day, hence the increased choral forces and intended use of doubling instruments, as was customary in the late 17th century. Daucé completes a version “en symphonie” based on instrumental suggestions by Cosset’s contemporary in Strasbourg and Meaux, Sébastien de Brossard.

The Missa — along with the other lesser-known pieces on this recording — represents a unique blend of Renaissance stile antico polyphony with the expressive gestures and modern sounds of the Italian Baroque, with echoes of Gabrieli and Monteverdi. The music, though, retains a distinctly French character, described at the time by Father Mersenne in his famous 1637 treatise, Harmonie Universelle, as a “perpetual sweetness” in contrast to the “extraordinary violence” of the Italian style.

Cosset’s mastery of vocal polyphonic writing is on full display in the two outer bold statements of “Kyrie” (à la Gabrieli) contrasted by the more intimate four-voice central quartet for “Christe eleison,” with its elegant paired imitation à la Josquin des Prez.

The largely homophonic “Gloria” is beautifully dispatched by Daucé’s ensemble with a leanness and clarity of line, highlighting Cosset’s voices and orchestra — both solo and tutti— in the framework of the cantata-like grand motet style, made popular by Lully and Charpentier.

Jean Veillot’s short, eight-voice “Ave verum corpus” is a real find, with individual solo-lines given expressive weight against the tutti voices.

The two plainchant hymns (by Mignon and Robert) are beautifully intoned by unison male voices, creatively doubled by the hollow-sounding, trombone-like serpent.

Pierre Robert’s “Christe redemptor omnium,” for eight voices and orchestra, is a classic example of the French grand motet popularized at the Chapelle Royale, where Robert served after his years at Notre-Dame. This carefully crafted work displays the skillful incorporation of large forces (orchestral and choral), solo voices, and an opening orchestral sinfonia. Daucé and his virtuosic ensemble bring a special sensitivity to this piece by matching orchestral balance and phrasing with the expressive inflection of the sung lines.

André Campra began service at Notre-Dame in 1694, leaving in 1700 to continue his successful operatic endeavors. He maintained ties to sacred music composition and, in 1722, succeeded Michel-Richard Delalande as composer to the Chapelle Royale, where he remained until his death in 1744. He left behind more than 30 grand motets.

Campra is best known for his Requiem setting of 1700, in which he masterfully distilled all the current stylistic musical traits — from the traditions of choral polyphony at Notre-Dame, to styles “antico” and modern, to the grand and petite motet and the influence of Charpentier (including his use of the solo male vocal trio), to the vocal graces of the skilled operatic female singers (who were admitted at Notre-Dame).

Daucé’s sensitive and lean approach to the Requiem is most welcome, removing years of preponderance and unnecessary weight. The opening movement’s A-B-A structure (Requiem – Te decet hymnus – Requiem) is beautifully elucidated by these performers, balancing the austerity of the opening cantus firmus chant in the tenor with the light hearted, quick-moving “et lux perpetua.” The male trio “Te decet hymnus” is underpinned by archlute continuo, contrasting with Campra’s accompanimental string sonority. The return of “Requiem aeternam” (minus the opening string introduction) is well-paced and allows the piece forward motion.

In the graduale-setting of the third movement, the performers’ careful attention to Campra’s use of silence in the repeated utterances of “non” (“non timebit”) bring great drama, recalling a technique Handel would employ in his Chandos Anthems.

One slight disappointment in this performance of the Requiem is Daucé’s ornamental overuse of appoggiatura and suspension to delay the resolution of chords at almost every big choral cadence. While technically it is an acceptable practice in the canon of French Baroque agréments, its excessive deployment comes off as cloying and sentimental.

The recording’s final track is a Holy Week motet of Pierre Robert: his eight-voice double-choir “Tristis est anima mea.” Its inclusion here seems a fitting end as a reflection on the Parisian choral style of polyphonic mastery that would endure until the end of ancient régime.

Jeffrey Baxter is a retired choral administrator of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, where he managed and sang in its all-volunteer chorus and was an assistant to Robert Shaw. He holds a doctorate in choral music from The College-Conservatory of Music of the University of Cincinnati and has written for BACH – The Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute, The Choral Journal, and ArtsATL. For Early Music America, he recently reviewed a film of Heinrich Schütz’s Auferstehungs (“Resurrection”).