by Aaron Keebaugh

Published November 4, 2024

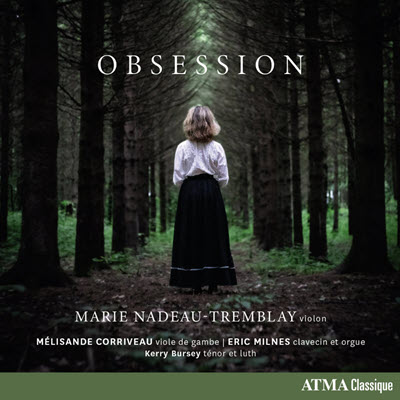

Obsession. Marie Nadeau-Tremblay, violin; Mélisande Corriveau, viola da gamba; Eric Milnes, clavecin; Kerry Bursey, tenor and lute. ATMA Classique L2825

As she rises ever higher on the early-music scene, Canadian violinist Marie Nadeau-Tremblay has displayed an improvisatory flair as brilliant as you might hear from the most seasoned professional. A creative thinker, her repertoire choices routinely shed light on lesser-known figures, and she has staked her claim as a vibrant chamber musician and soloist in works by Johan Helmich Roman, Johann Schmelzer, Heinrich Biber, and an array of others. As revealed in her albums with Montréal’s Les Barocudas ensemble, Nadeau-Tremblay plays the violin with uncommon immediacy, spontaneity, and rhetorical ease. (In 2023, she gave an unforgettable solo performance at EMA’s Emerging Artists Showcase in Boston.)

With Obsession, her most recent release, improvisatory gestures serve a highly dramatic purpose. Built upon repetitive grounds, the lines of this music stew and ruminate like the obsessive thoughts suggested by the album’s title. That the pieces by Biber, Dieterich Buxtehude, Louis-Gabriel Guillemain, and François Francoeur are all cast in the minor key only enhance the violinist’s innate feel for angst and apprehension.

The first of Biber’s Rosary Sonatas conveys such fervent storms and stresses. Nadeau-Tremblay tears through the quick-changing emotions with the nervous abandon of a fever dream. Clavecinist Eric Milnes brings little solace in the central sections, even as his figures lilt. Their superb sense of style does little to quell the fiery tension, and the reading culminates with a Promethean flair.

Biber’s Sonata for Violin No. 2 in D minor also surges like a rippling torrent. This tempest roils from the bottom up. Mélisande Corriveau’s viola de gamba provides sturdy support for Milnes to stack resonant organ harmonies. That leaves Nadeau-Tremblay free to toss off wild flourishes with a tone that ranges from silver to deep mahogany. Colors only flash vibrantly from there, with shifts to the major keys bringing momentary splashes of light. This is chamber music at its finest, and the trio fittingly never settles into the usual back and forth.

Buxtehude’s Trio Sonata in G minor brings greater congeniality. Milnes and Nadeau-Trembley play with a sumptuous warmth that Corriveau’s bass line brings to sweetened fruition. Yet here, too, the zest is never entirely absent. The second movement involves a buoyant play of rhythm and texture, each player more urgent than the next. But they leave room for humor. In the Allegro, the lines dovetail with an impish glee broken only by the sullen Grave. The concluding Gigue frolics even as the minor key casts a slight cloud over this party.

Buxtehude’s Trio Sonata in A minor likewise see-saws between limpid vitality and North German seriousness. Here, Nadeau-Tremblay shines through the continuo’s reedy support, like a spider web hanging on an oaken branch.

But the musicians’ virtuosity still makes for pure fun. Guillemain’s Amusement for Violin Solo, Op. 18, No. 1 unfolds as a series of difficult variations. Nadeau-Tremblay is firmly in her element; she handles the wide leaps of each line with a crispness that never distorts the flow.

She does the same with the dark ambience of François Francoeur’s Sonata for Violin and Continuo G minor, Op. 2, No. 6. In the opening Adagio, Nadeau-Tremblay’s presence is spare, even distant. Yet she revels in the music’s sense of freedom by lingering in every emotional crest and valley. The dance movements provide ample counterbalance. The Sarabande is fittingly seductive; the final Rondeau charges forth with real Baroque fire.

The trio’s take on Michel Farinel’s version of “La Folia” also lets the rapture run high. But even here everything builds to satisfying payoff. Variations skip along, leap in myriad directions, and flare into a final rush. Through it all, Nadeau-Tremblay works like an actress by exploring every emotional dimension. This is not mere obsession but full-on rumination, played out in music.

The Anonymous “Une juene fillette” brings momentary solace. Kerry Bursey’s tenor is clear and ringing, setting the tone for the gradual unfolding of the musical vitality. As with most obsessive thoughts, there are moments of peace and certainty — vivid moments of light amid the darkness.

Aaron Keebaugh’s work has appeared in The Musical Times, Corymbus, The Classical Review, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, and The Arts Fuse, for which he serves as regular Boston critic. For Early Music America, he recently reviewed Deep River: Spirituals’ Cross-Currents.