by Karen M. Cook

Published November 24, 2024

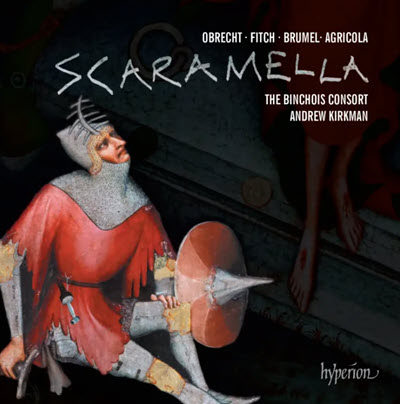

Scaramella, The Binchois Consort, directed by Andrew Kirkman. Hyperion CDA68460

One of the perils of preserving music in partbooks, as many fans and scholars of Renaissance music know, is that one or more of the books might be lost. This is a particularly dire situation when the partbooks in question contain the only known version of a work and we can’t hear it fully and as originally notated. Sometimes we get lucky: the missing book turns up — as with Laurie Stras’ discovery of the lost alto book from Maddalena Casulana’s first book of madrigals. Such luck is, unfortunately, all too rare and plenty of works still remain consigned to silence or to the imagination.

However, it also happens that a scholar versed in the style and practice of a given composer might try their hand at filling in the gaps.

Such is the case with musicologist Philip Weller, who drew on his knowledge of Jacob Obrecht’s style to reconstruct his fragmentary motet Mater patris – sancta dei genitrix some years ago. In 2010, he and Fabrice Fitch began similar work on Obrecht’s Mass on the “Scaramella” tune, which survives only in the altus and bassus partbooks. They noted that since the Mass made use of a known cantus firmus, the tenor might be somewhat reasonably reproduced; from there, the discantus could be constructed. As Fitch notes in a related article, he and Weller made good progress, completing the two Kyries and part of the Gloria, but not much more was done until 2018, when Weller finished the Agnus Dei and part of the Sanctus.

Unfortunately, Weller passed away shortly thereafter, leaving the musicological world in mourning and the work unfinished. Fitch then completed the remainder of the Mass, which fittingly acts as the centerpiece for this new album by the Binchois Consort, Weller’s frequent collaborators.

The newly reconstructed Mass and the aforementioned motet that Weller had also reconstructed are bookended by two settings of “Scaramella” by Josquin and Compère, plus Fitch’s own setting of Planctus David, a newly composed tribute to Weller. The album begins and ends with two more motets with connections to Weller: Alexander Agricola’s Sancta Philippe Apostole and Brumel’s Philippe, qui videt me both signal Weller through the name Philippe, and the Brumel is yet another example of Weller’s reconstruction efforts.

The album is a remarkable musical testament to a scholar-collaborator who was clearly a dear and treasured friend, to which the opening cry of “Philippe” immediately testifies. Recognizing that the reconstructed works are “best guesses” for what might have been, the results are musically engaging; the opening Brumel is joyous, and it is tempting indeed to hear the phrase “anyone who sees me also sees my father” as a bittersweet acknowledgement of Weller’s role in the work’s performance.

The Mass is a tour de force of Obrechtian counterpoint, with all sorts of interesting versions of the cantus firmus showing up throughout; the reduced textures at the beginning of the Gloria are particularly appealing, and the startling dissonance at the end of the Pleni sunt coeli is beautifully crunchy. The Agricola is more somber in tone, a fitting conclusion to the disc. The more intimate acoustic (meant to reflect the smaller side chapels in which these works were most likely performed) is effective throughout, but perhaps nowhere as much as in Fitch’s powerfully stark lament. With regard to musicological prowess, musical skill, and personal sentiment alike, it’s an album well worth a listen.

Karen M. Cook is associate professor of music history at the University of Hartford. She specializes in late-medieval music theory and notation, focusing on developments in rhythmic duration. She also maintains a primary interest in musical medievalism in contemporary media, particularly video games. For EMA, she recently reviewed the forgotten Flemish composers from Spain’s Golden Age.