by Michael Walker II and Philip Spray

Published November 30, 2024

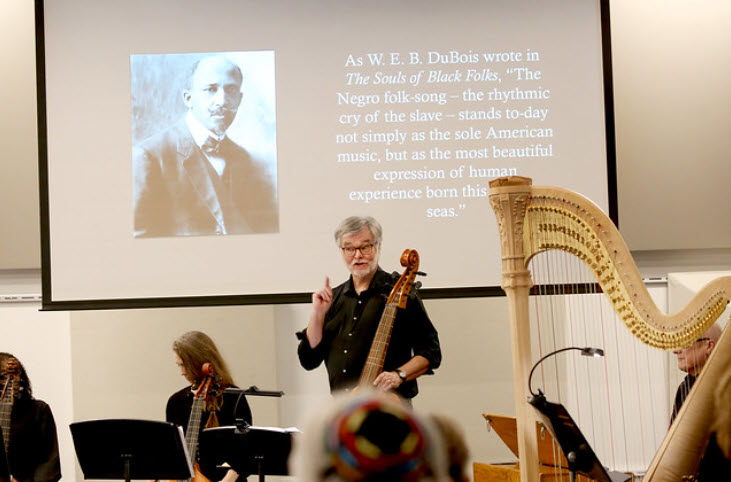

A singer and viol player turn the New World’s first folk music — the quintessential American sound — into American broken consort songs

A presentation from the 2024 EMA Summit, drawn from Alchymy Viol’s album ‘Deep River: Spirituals’ Cross-Currents’

What do Negro spirituals have to do with a consort of viols? Great question!

Philip Spray: A consort is a family of instruments — that is, different sizes of the same instrument “consorting” with one another, as in a consort of viols, a consort of recorders, or dulcians, or crumhorns, and so on. But if they start consorting with an instrument outside their family, the consort becomes broken — and wonderful things happen.

When period instrument players and listeners hear the term “broken consort” they might think of Thomas Morley’s First Book of Consort Lessons, from 1599. His mixing of violin, flute, bass viol, lute, cittern, and bandora became a standard for a broken consort in England, although across Europe all sorts of combinations and voices were devised — surely due, in part, to what was locally available.

Despite which instruments consorted together, two foundational elements keep appearing in broken consort songs.

The first is the song. There were art song settings, but the ones that continue to attract me are the consort settings of common songs, the popular songs such as O Mistress Mine as might have been sung in Shakespeare’s plays. (And remember that Shakespeare was not a high-art playwright, but a playwright for the masses). So across Europe, consorts were built on the popular songs of France, Germany, Scotland, Poland, and so on.

The second element is a consort’s “national sound.” It is a concept that has lost importance in modern classical music. In the times of the original broken consort songs, however, it was proudly valued, natural, and essential. So English music sounded English, French music proudly sounded French. Those national sounds, at some point, must have had something to do with the rhetoric of their national tongue. So if a French composer set a sung version of the popular tune Une Jeune Fillette for a consort, chances are that the consorting will “speak” with a recognizably French accent.

Consequently, the 16th and 17th centuries enjoyed a wide variety of consort songs, unique in the origin of their national dialects. And that raises the question: What might have American Broken Consort Songs sounded like?

Well, you’d need a popular American song, and an American sound.

As for what the American song might be, no less than the great Antonin Dvořák offered an opinion. In 1892, Dvořák was invited to New York’s National Conservatory of Music of America to help figure out what kind of music could be called truly “American.” Soon after arriving, Dvořák met the young Black vocalist and bass player Henry Thacker Burleigh (1866–1949) who introduced Dvořák to Negro Spirituals. A year later, Dvořák was quoted in the New York Herald:

“I am now satisfied that the future music of this country must be founded upon what are called the Negro melodies… They are the songs of America and your composers must turn to them. In the Negro melodies I discover all that is needed for a great and noble school of music. They are heartbreaking, tender, passionate, melancholy, solemn, religious, bold, merry, gay, gracious or what you will. It is music that suits itself to any mood or purpose. There is nothing in the whole range of composition that cannot find a thematic source here.“

‘I turned to spirituals to make sense of the world and bring myself much-needed comfort’

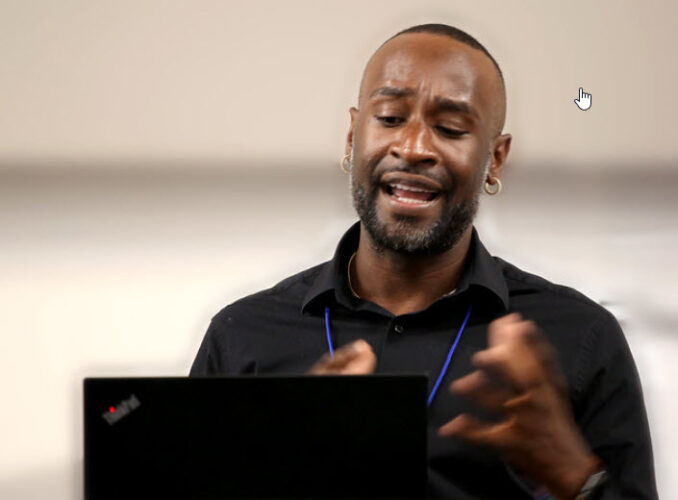

Michael Walker II: For me, spirituals have played an integral role in my life. I grew up singing in the church and was a choir kid. They feel as natural to me as language itself. In fact, one could argue that language is the first music we are introduced to, as we mimic and produce various sounds and inflections to communicate and be understood. That said, spirituals have always served as my musical inspiration and happy place.

This project was born out of the isolation and social reckoning of 2020. That uncertain time — the pandemic, the outrage over police brutality and systemic violence against Black people, the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement — highlighted the persistent issues of racism and its lasting consequences. Amidst the anger, despair, and loneliness, I was reminded of the therapeutic power of spirituals to heal and provide peace during times of hopelessness. I turned to spirituals, as I did when I was a child, to make sense of the world and bring myself much-needed comfort.

During that period, I decided it was time to focus on the music of traditionally marginalized communities, particularly the spiritual, composed by African American composers. So I reached out to some friends well-versed in this repertoire to help guide my exploration.

As I began my journey, I couldn’t help but notice the philosophical parallels between early music and spirituals. The ancient Greek “Doctrine of Affections” — a belief that music has the ability to elicit specific emotional responses in listeners — has been a guiding principle in my work as an early musician. This notion aligns with spirituals, which are often spontaneous outbursts of intense emotion. These songs were intentionally sung to ignite the passions of the listener, providing catharsis, and promoting overall well-being.

Historically, spirituals were “composed” as early as the 17th century when enslaved African people were brought to the Americas, making them the first folk songs of the New World. Generations of African Americans passed these songs down orally, using them to cope with their traumatic experiences. The texts of these plantation songs speak not only to the Black condition but also to the human condition, making them inclusive of all humanity. As W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in The Souls of Black Folk, “the Negro folk-song — the rhythmic cry of the slave — stands today not simply as the sole American music but as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side of the seas.”

Philip: And to honor and play these most beautiful expressions of human experience, we turned to the viol consort. Historically, viols have been called the most human sounding of all instruments. Perhaps it was a viol player who first said so, but it remains a fact that their range from high to low is huge, their sound is more plaintive than pungent, they are physically lighter than cellos, and their strings are under much less tension. And those strings — they are made of animal gut. They are organic. So when that organic material is vibrated to make a sound, it is the closest thing to the human vocal cords.

Michael: One day, while rehearsing the famous song of sorrow “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” arranged by Harry T. Burleigh, I was deeply moved by its simple yet expressive text and haunting melody. It reminded me of the viola da gamba in its ability to convey both sadness and joy. Drawing inspiration from Benjamin Britten and his partner Peter Pears, who helped revive Henry Purcell’s music by creating modern realizations of his songs, I sought to do something similar with spirituals. So I approached my dear friend Phil Spray to explore a project that would reinterpret the music of Black composers using a viol consort.

Michael: Spirituals were composed for group singing as a way to preserve the stories of joy, sorrow, despair, and hope of African Americans’ lived experience through music and lyrics. These songs were often inspired by divine inspiration at camp meetings, an outdoor religious revival that included passionate displays of emotional and physical expression. Enslaved Africans believed that music played an essential role in their society, and through the power of voice, dance, toe-tapping, clapping, and shouting, they asserted moral agency and dignity in their day-to-day lives. They served as a form of spiritual rebellion, allowing the individual and community to voice, manage, and release their emotions.This highlights the versatility of spirituals, as they can be performed either as solo pieces or as part of an ensemble.

Philip: This is also true of viol consorts, in which instruments are not soloists, but choir members.

Coded Language and Rhetoric

Michael: The enslaved were removed from their native languages and taught only the basics of communication, depending on their owners. The African American dialects evolved out of this experience, and I believe this dialect should be respected when singing spirituals in a historically informed manner.

The rhetoric in spirituals is a reflection of their creators’ daily circumstances and their use of Biblical poetry, deeply rooted in the liberation narrative of the Old Testament Israelites and the life, death, and promise of salvation found in the Christ narrative. Songs like “Joshua Fit da Battle of Jericho” evoke the story of the walls of Jericho “tumblin’ down,” symbolizing the hopeful collapse of the horrific American system of slavery. Other spirituals, such as “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word,” draw direct parallels between the crucifixion of Christ and the lynching of Black men in the United States, using Biblical allegory to convey the pain and enduring hope of oppressed communities.

To help make sense of a cruel world filled with moral contradictions, spirituals often juxtaposed sharply contrasting themes while using satire and coded messages in its lyrics. For example, the prevailing theme in “My Lord What a Morning” is assurance amid judgment; and in “Give me Jesus” it is the acceptance of life in death. One of my favorite American hymns, the spiritual “Steal Away” has been believed to be coded instruction on how to access and escape to the North (Canada) via the Underground Railroad. “I Don’t Feel No Way Tired” and “Hard Trials” cleverly disguised allegorical and biblical language to take subtle jabs and express resistance against their tyrannical oppressors without being immediately discovered. Under such repression, coded language contributed to the resilience of the enslaved communities, allowing them to express dissent within the constraint of circumstances was essential to their survival.

‘Our aim is to create an intimate chamber music experience that empathically moves and educates diverse audiences’

Michael: During the Reconstruction era, as Phil mentioned, African American baritone and composer H.T. Burleigh played a pivotal role in preserving and popularizing spirituals. His groundbreaking collection The Negro Spirituals (1917) displayed the beauty and emotional depth of these songs, making them accessible to wider audiences. Burleigh,with the help of his contemporaries who performed his music Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, and Roland Hayes helped elevate spirituals from folk music to concert music.

Our aim with this project is to create an intimate chamber music experience that empathically moves and educates diverse audiences, whether they are familiar or unfamiliar with the sounds of the viol consort and/or these traditionally marginalized Black composers.

The Problems of Copyright

Philip: At this point, we had all our ingredients for the Deep River project: American songs and an American sound. Michael chose his favorite spirituals, and we were off to make American broken consort songs. But soon after, I discovered that over half of that music was still under copyright. So I would not be allowed to change anything in the original piano settings — not rhythms, not harmony, not the numerous arpeggios, not the voice leading, nothing.

Then I thought back to historical broken consort models. The first one was the Lawes Harp Consorts. A harp could play those numerous arpeggios. It could serve as a continuo instrument as well as a melody instrument, and its percussive pluck would balance the viols’ gentle bowing waves. (But it needed to be a modern pedal harp because the highly chromatic harmonies could not be changed. Chromatic harmony is what the pedal harp was made for.) Right away, it worked beautifully.

Then I turned to the Morley broken consorts that used a violin. So I added a gut-strung violin and viola. They were especially good for navigating the very high figures from the keyboard arrangements, probably more effectively than a gentle treble viol. These upper instruments came together with the harp and viols especially in “Deep River” and “Give Me Jesus” by Hogan and “Steal Away” by Burleigh.

Philip: And what can a viola da gamba do that other instruments can’t? Play the lyra way: bow a chord across up to six strings. To my ear, the English lyra viol had always been the heavy metal instrument of the 16th century. It was like Pete Townsend of The Who and his trademark windmill guitar stroke. The piece that suited this the best was “Every Time I Feel the Spirit” by Nolan Williams, Jr. So I made a lyra viol part and we had our lyra-viol consort.

Finally, if you work with period instruments, at some point you think about a keyboard basso continuo instrument. These pieces were well-suited to having something beneath the viols and harp, but a harpsichord wasn’t right. And mostly not the box organ, either. I wanted something that sounded more American: a pump organ. I had grown up with one in the family living room and had played everything on it from Bach to “Light My Fire.” Luck would have it that in Indianapolis, where several of us live, a gentleman collects historic, portable field pump organs. These were the small instruments that the military used for religious services in the battlefield, or that a church might use underneath a tent. Our keyboardist Tom Gerber went to his home and was greeted by seven small pump organs in a circle. Each had a different tone, a different touch, and were tuned to a different “A.” It should not have been a surprise because if such an organ is the only thing playing in a camp on Iwo Jima, the tuning doesn’t much matter. For our purposes, the best of these instruments had been built in Vermont in 1945 and was tuned at A=439.5. In true early-music fashion, the rest of us re-tuned our strings to that A=439.5.

Philip: Is our Deep River project a one-off? We hope not. It is, however, just a first step. If spirituals are the earliest American music, then perhaps theory teachers can use a short spiritual tune for their lessons and assignments in counterpoint. Many short tunes in the public domain appear in facsimile in Slave Songs of the United States 1867. Perhaps Viola da Gamba Society bastarda players, for example, might compose new settings for some of those same tunes.

Many high school choirs sing Burleigh’s “My Lord, What a Morning,” and his choral arrangement is well-suited for a viol consort, with a treble viol at the top, and might be played in the classrooms of viol teachers. Or you could set a spiritual keyboard arrangement for a different instrument, as our own Stephanie Hall has set Burleigh’s “Through Moanin’ Pines” for solo pedal harp.

Our hope is that talented composers in our period-instrument world might reach out to new listeners with American broken consort music. They’ll come to love it as much as we have, and at the same time begin to recognize the trials in which these American songs were born.

Countertenor Michael Walker II (he/him) performs nationally, specializing in early and contemporary music. A graduate of Indiana University’s Historical Performance Institute, a Sphinx LEADer alumnus, and currently senior development officer at the ACLU of D.C., he combines artistry with a dedication to social justice. www.mwalkercountertenor.com

Philip Spray is a teacher, performer on period instruments, and a founding member of Alchymy Viols, Musik Ekklesia, and the Indianapolis Baroque Orchestra.