by Aaron Keebaugh

Published December 20, 2024

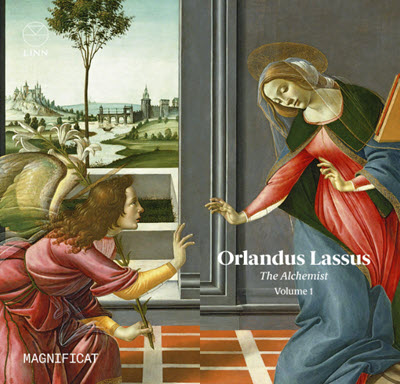

Orlandus Lassus: The Alchemist Vol 1. Magnificat Consort, led by Philip Cave. Linn Records CKD 660

Parodies make up some of the most decorative examples of 16th-century polyphony. But they are less about strict technique than about personal creative whim. Composers like Josquin, Palestrina, and Orlandus Lassus (to name only a few) routinely expanded and expounded upon even the bawdiest madrigals and chansons for large-scale sacred works. In the process, they made parody an art unto itself.

But because of that, it can be difficult to parse where the source music ends and the new voice begins. The originality of Lassus, however, manages to sound out through a finely woven mix of the earthly and the spiritual.

That’s just what Philip Cave and the vocal ensemble Magnificat explore with The Alchemist, the first volume of a planned three-volume series. This double disc pairs Magnificats by Lassus alongside madrigals on which they were based. Heard side-by-side, the sacred settings and their secular sources come off as an intriguing game of pairs.

Yet there’s more to this approach than the purely musical. The source texts haunt Lassus’s scores even when he conveys the somber ambience of the Marian prayer. For example, Alessandro Striggio’s “Ecco ch’io lasso Il core” relays the pains of self-sacrifice through sarcasm. Even when Lassus transforms those passages with a sense of conversational buoyancy, Striggio’s tension remains, and the music suggests that only prayer can assuage such raw emotions. Cave calls this process “experiencing the alchemy,” and his lead through these stellar performances further reveal that effect.

Madrigals such as Noletto’s “Quanto in mille anni,” a charge to gaze upon a beautiful person should one choose never to fall in love, teases at Lassus’s Marian context. Cave elicits a gentle lilt as even as dissonances routinely sting the ear. And the singers transform mundane desire into spiritual triumph.

They do the same with Jacques de Berchem’s evergreen “O s’io potessi donna,” a vivid and visceral depiction of being caught in a long embrace. Here, too, Cave channels the original through trumpeting sonorities that range from assurance to outright conviction.

Cipriano de Rore’s “Alma real” bears a more direct connection with its source subject. Composed around 1560, the madrigal praises Margaret of Parma in reverential tones. Lassus’ setting, possibly composed as a gift to Margaret, suggests wayward restlessness. The singers lean into the jarring shifts between chant and polyphonic sections, as if torn between hushed reflection and exuberance.

Lassus’ Magnificat “Vergine bella” is much more complementary to Rore’s original madrigal. Itself a prayer to the Virgin Mary, Rore’s setting unfolds in such soft layers of sound that it is easy to forget the textural intricacy. Lassus plays upon that effect by drawing out each dovetail turn, though the sumptuousness remains. Cave and the ensemble strike a superb balance between structural clarity and beautiful sonic sheen.

Other pieces suggest darker emotions. Anselmo de Reulx’s “S’io credessi per morte” conveys the suicidal overtones of Petrarch’s text through harmonies that grind and crunch together. However harrowing the experience, the madrigal’s protagonist is reluctant to carry out such a violent act. The music seems to say that living with that pain, no matter how unbearable, is the only way forward. Lassus makes that resolution all the palpable through sweeping counterpoint. Whatever angst remains rises to the surface in the duets between treble and bass voices.

By contrast, Lassus’ Magnificat on Giovanni Maria Nanino’s “Erano i capei d’oro” retains the text’s emotional crests and valleys. The music stutters and jolts more than it flows, and its haunting chromatic shifts offset any of the prayer’s wistful solace.

That’s the opposite effect of the Magnificat built upon Cristobal de Morales’s “Quando lieta sperai,” where context defines content. Sudden swells in dynamics conjure feelings of bittersweet heartbreak. It suits Lassus’s setting, where bright timbres and cavernous basses combine in prayerful fervency. Only in the soft cadences does the music find any consolation.

The Magnificat upon Striggio’s “D’ogni gratia e d’amor” similarly see-saws between vigor and restraint. Built on a madrigal that praises Queen Elizabeth, Lassus’s rewrite leaves enough contrapuntal slack for the voices to emerge with freedom.

In that, Lassus allows for complicated feelings to rise to the surface. His take on Rore’s “Da le belle contrade,” which tells of a separation between two lovers, retains all the anxieties of a couple caught in a quarrel. Prayers to the Virgin Mary, Lassus’ Magnificat suggests, need not be stagnant and bound to ritual. They are, in their own ways, very personal expressions of fear and loss amid abiding love.

Aaron Keebaugh’s work has appeared in The Musical Times, Corymbus, The Classical Review, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, and The Arts Fuse, for which he serves as regular Boston critic.