Restoration means bringing an instrument back to a playable condition. Conservation is about preserving an instrument in its current state and ensuring its survival. Is “restorative conservation” the solution, or just the latest trend?

Restoration can be the opposite of conservation, because you are actively doing things to the instrument that are irreversible.

This article was first published in the September 2024 issue of EMAg, the Magazine of Early Music America

Early-instrument restoration might seem like a straightforward process. Acquire a two- or three-hundred-year-old clarinet or harpsichord in rough condition, find a qualified technician, and have it brought back to its original state.

Questions abound. How much reworking is too much? Should the instrument be made playable or simply maintained in its present condition? And in the case of instruments that have been modified over the centuries, what is, in fact, “original”?

There are no set answers. Indeed, even the definitions of restoration and conservation are debated. And what makes sense for one group of instruments doesn’t necessarily work for another. In short, it’s complicated. What is clear is that restoration can unlock the past and give today’s musicians a chance to play the instruments that composers like Girolamo Frescobaldi or C.P.E. Bach were writing for hundreds of years ago.

A little background. Most musicians in the early-music world play on reproductions, modern instruments that have been carefully patterned on originals from past centuries. The reasons are simple.

First, in most families of Baroque instrument, extant originals are hard to find, excessively fragile, wildly expensive, or all of the above. Few Medieval and Renaissance instruments exist today, and often what we hear are hypothetical models based on paintings, tapestries, stained glass, and descriptions from treatises and literature.

Such rarity is especially true in the drum world, where nearly all such instruments from the Baroque era are in museum collections, according to Jonathan Hess, timpanist for Boston’s Handel and Haydn Society. Though it might seem counter-intuitive, metal doesn’t last as well as wood, and the steel and copper used in old drums was often melted down for military use in times of war. (In a huge discovery for brass instruments, a shipwreck discovered in 2023, off the coast of Croatia, held some 15 trumpets from the late 16th and early 17th centuries, or twice the number found in museums.)

Hess plays on contemporary German-made Lefima timpani that are based on Austrian Baroque models. He calls them “modernized replicas” because they make concessions to “modern expectations and versatility,” with a slightly different bowl shape and an extended collar that satisfies today’s listeners, with more resonance and more volume.

Second, original instruments come with all kinds of inherent issues that can be big hurdles for professional musicians who need a high level of dependability and have to play a vast range of early music with multiple ensembles. “Part of the standardization in the historical performance movement is obviously for practicality’s sake, because if musicians are traveling all over the place, they have to know when they get off the plane they will be able to play with the ensemble they are hired to play with,” says Thomas Carroll, a Boston-based restorer who performs as principal clarinetist with multiple ensembles, including the Bay Area’s Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra.

We often hear ‘modernized replicas’ that make concessions to ‘modern expectations and versatility’

A big challenge is pitch. Today, many Baroque ensembles perform at 415 cycles a second, but tuning can vary widely among original instruments, sometimes even among those made in the same year and in the same city. The National Music Museum at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion owns harpsichords that are tuned anywhere from 392 to 473 Hz, including an instrument built in the late 1600s and attributed to Giacomo Ridolfi at 410 Hz.

Third, there are more skilled instrument makers than ever before, and the quality of the resulting instruments is better than ever, making them a more enticing option. “Replicas have changed a lot over the years,” says Michael Lynn, professor of recorder and Baroque flute at Oberlin College and Conservatory in Ohio. “The quality of replica flutes now is vastly better than when I started playing Baroque flute almost 50 years ago.”

Fourth, playing an original instrument can be detrimental, maybe even irresponsible. Because original flutes from 1750 and earlier are so rare, performers almost never use them regularly for concerts and rehearsals. “People often feel like that is a little too much wear and tear on a flute from that early,” Lynn says. Such thinking changes with later flutes, which were made of durable metal alloys beginning around 1845 and are somewhat less scarce today. Thus the cost of making a deluxe copy of a 19th-century keyed flute might be more expensive than buying an existing original.

Many copies today are very good, but there is something special about antique instruments

But if contemporary instruments dominate today’s early-music world, it doesn’t mean that musicians don’t still pine to perform on originals — if not on a regular basis, at least on special occasions or for recordings. Sometimes, they acquire an old oboe or horn or viol on their own. In other cases, they perform on historic instruments that are in public collections such as the National Music Museum, which regularly presents concerts featuring its vast holdings.

“Most people who play Baroque flute have probably never played an original Baroque flute,” says Lynn, who has a collection of about 150 historical flutes. “Even though copies that we play on are very good, there is something special about the antique instruments.”

Restoration vs. Conservation

The first challenge in undertaking a restoration is finding an extant original instrument. They are sold by dealers or auction houses, and sometimes can be purchased directly from collectors. Antique-shop treasures occasionally turn up: a piece of “painted furniture” at a St. Louis shop turned out to be a rare, c.1590 virginal made by Francesco Poggi of Florence. Still, experts believe that a great many of the important harpsichords and fortepianos are known within the field, because their size means they can’t easily be lost in someone’s attic. But that is not true for, say, vintage flutes, where the pace of discovery is still relatively high.

The next challenge is deciding if an instrument can be restored at all. Old clarinets, for example, can reach a point when they are beyond the point of usability because of the decades of hot air and saliva blown through them. “Unlike string instruments, where the instruments often get better as they age because the wood gets drier or the wood gets more used to vibrating at certain frequencies,” explains Carroll, “wood for clarinets and other woodwind instruments tends to degrade over time.” He has a collection of original clarinets that date from the end of the 18th century through a set from 1879 that were used in the Meiningen Court Orchestra that premiered works by Johannes Brahms.

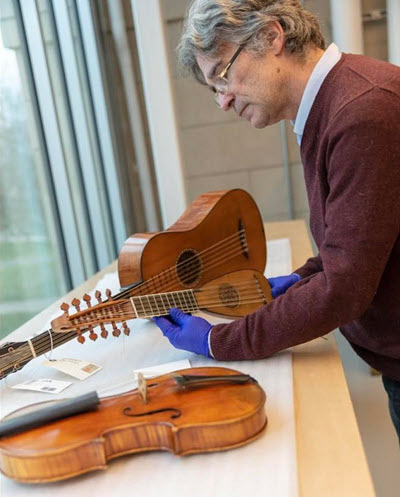

Just because an instrument can be restored, should it be restored? This is where the thorny question of conservation vs. restoration comes into play. Conservation means essentially preserving an instrument in its current state and striving to provide the best possible conditions for its survival. A good example of such an approach took place in 1990 when the National Music Museum discovered that a 1582 bass viol in its collection, by Ventura di Francesco de’Macchettis Linarol, was essentially pulling itself apart. The institution hired a conservator to disassemble and reassemble it, and thus stabilize it. Restoration, in contrast, generally means bringing an instrument back to a playable condition. But there is nothing black and white about these terms.

“Restoration can be the exact opposite of conservation in some ways, because you are actively doing things to the instrument that are irreversible. If you do something to improve the sound, you can’t bring it back to what it was,” says Darryl Martin, a longtime keyboard conservator who has been on the staff of the National Music Museum since 2022.

About three years ago, at an auction, the museum purchased a ca. 1540 polygonal Sicilian virginal (a harpsichord with the strings parallel to the keyboard) with the hope that the instrument could be made playable again. But it turned out that wood filler was precariously holding the bridges in place, and the strings were almost touching the soundboard. Martin, who wrote his doctoral dissertation on English virginals, determined that it could be fixed, but the 57-inch-long instrument would not be the same. If he were to restore it to playability, he says, it would “totally alter the sound, because I’m taking the soundboard out. I can’t put it back in with the same [string] tension.”

Although there are no hard and fast rules, ethical guidelines in the museum world generally call on conservators to take a minimalist approach to repairs and restoration. If not “do no harm,” at least do as little harm as possible. In this case, that meant conserving the Sicilian virginal in its present state. Is there disappointment among museum leaders over the decision? “I’m sure there is,” Martin says. But he feels that everyone agreed the approach was the proper one, and that the virginal as is will be an ideal instrument for today’s makers to copy.

Would a private collector, who was not bound by similar guidelines and who was intent on making the virginal playable, have made a similar decision? “If it’s in private hands, that just comes down to what somebody wants to do with their private property. There are ethical things and less ethical things,” says Arian Sheets, curator of stringed instruments at the National Music Museum.

‘There are ethical things and less ethical things’

Leaders at Mount Vernon, in Virginia, made a similar decision about a decade ago when it came to a 1793 two-manual harpsichord that George Washington purchased for his step-granddaughter, 14-year-old Eleanor Parke Custis (“Nelly”), whom he and Martha raised as their own.

The English instrument by Longman & Broderip — what John Watson, another veteran keyboard conservator, called “one of the two most historically vulnerable artifacts in the mansion” — had long been on display and suffered from the frequent open doors and fluctuations in temperature and humidity.

Instead of making any radical changes to the instrument, Mount Vernon’s leaders hired Watson to build an exact-as-possible replica of the instrument that would be placed on view in the main house, with the original being moved to safer quarters in the adjacent Donald W. Reynolds Museum. During a two-year process, Watson did minor conservation of the original instrument, which he closely studied, and constructed the copy.

“That [new] instrument, absolutely, was intended to be playable, to see what George Washington’s harpsichord sounded like,” he says. “But my emphasis as a maker was really for the research.” He made a copy as faithful to the original as possible, “in order to learn what it has to tell us about 1790s harpsichord making, which was pretty darn interesting.”

By 1793, the fortepiano was making inroads in the keyboard market, so the builders of Washington’s instrument created a design to try to compete with the newer inventions. These included what Watson calls a “Venetian swell,” which allowed the harpsichord to crescendo and decrescendo, as well as substituting the plectra (the tabs that pluck the strings) from the usual bird quills to a more touch-sensitive soft leather. “Really, what you are seeing is an effort to make the keyboard that is expressive, that is for the new aesthetic — a more romantic sound,” he says.

‘Restorative Conservation’

Watson, who served from 1988 through 2016 as the conservator of instruments and mechanical arts at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, advocates for what he calls “restorative conservation.” (He wrote an entry on the subject for the 2014 edition of the Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments.)

While such an approach still has the goal of making the instrument playable, it also puts an equal emphasis on preserving as much of the original instrument as possible and what he calls the “physical evidence” built into in it. He notes that tool marks or even the direction of a glue run can provide important clues about how an instrument was built. “It’s mind-boggling if you were to write down everything that an instrument could tell you about its original construction,” he said.

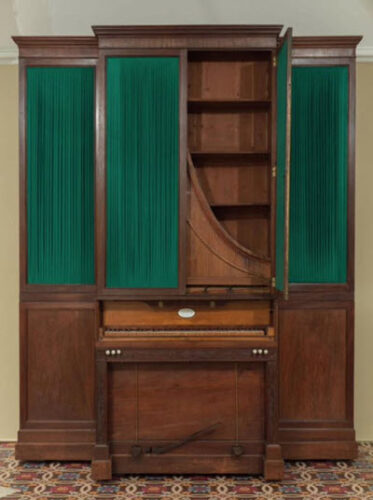

Watson put his philosophy of “restorative conservation” into practice when he restored an organized upright grand piano — a 9-foot-tall piano with the case positioned vertically and with two ranks of organ pipes on either side of the strings — that was acquired by Colonial Williamsburg in 2012. “There’s an instrument that is extremely rare,” the conservator says. “Literally, we don’t know of another surviving organized upright grand piano.”

Made by the English firm of Longman, Clementi & Co. in 1799, it was purchased by a prominent Williamsburg family, and its ownership changed several times over the years. It came to the museum in about a thousand pieces with the organ pipes smashed and buckled. Watson speculates the pipes were damaged during the Civil War when the family tried to save them from being melted down for bullets.

Because lead is so malleable, he was able to reshape most of the pipes to their original form, only needing to reconstruct a few. He also had to rebuild the piano action, which was missing. The whole project was like a giant puzzle, Watson recalls, and required “hours of head-scratching.” He tried to minimize damage to the instrument through “tricks of restorative conservation” like attaching woodblocks using easily reversible glue and drilling into those instead of the instrument’s original wood. In addition, he took some 1,500 photographs as he went along and compiled a massive report on the project to assist future researchers and anyone who might need to work on the instrument later — or, who knows, build their own organized upright grand piano.

If some kind of restoration is decided upon, another important question is to what state, or what era, should the instrument be returned. Ken Slowik, curator of musical instruments at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, offers a hypothetical example: Imagine a 17th-century harpsichord built by the Dutch-based Ruckers that underwent, as often happened in 18th-century France, what was known as a grand ravalement in which the instrument was reworked and enlarged. And imagine that, perhaps in the 19th century, its exterior was modified with new paint.

“If you were going to restore it,” Slowik asks, “what would be the proper point to which you should restore it? Should you just take away the 19th-century paint? Should you get back to the 18th-century French style? Or should you try to rebuild it, or unbuild it, more to what it started out as, which in many instances might mean a lot of work destroying the 18th-century fabric?” (In a similar debate over rebuilding Paris’ Notre-Dame Cathedral after a devastating fire in 2019, the French government decided the least controversial approach would be to use artisanal techniques to restore it exactly as it had been just before the fire.)

Back to Playability

As a restorer-performer, Thomas Carroll faced a similar dilemma. When he was studying in Europe, he obtained a clarinet by Parisian maker Jean-Jacques Baumann, built around 1802, that had been modernized with keys added beyond the original six and a hard-rubber mouthpiece. After comparing the measurements of the instrument to others by the same maker, he also discovered that someone had cut about 4 millimeters off the top joint (one of the two mid-sections of a clarinet with holes) to make its pitch higher — about 439 Hz compared to the original 432-435.

According to Carroll, there are no original clarinets or chalumeaux (folk-instrument predecessors to the modern-day clarinet) from the Baroque era in use as playing instruments. “They’re all safely behind glass in museum collections,” he says. Even for later periods, most clarinetists use replicas — although there are some players, like him, who sometimes perform on original instruments.

After he decided to restore the 1802 Baumann, Carroll first constructed a new barrel (the short section right above the top joint) that was 4 millimeters longer, thus returning the clarinet back its original length. He also crafted a replica of the mouthpiece, removed the extra keys, and made boxwood plugs to fill the unwanted holes.

Lynn owns an 18th-century flute made in Leipzig by Crone — the kind of instrument for which C.P.E. Bach was writing. When he acquired it as part of a group of six flutes, it wouldn’t play at all: A crack that ran all along the back of the head joint had reopened. That fissure had been repaired using metal pins that were drilled in sideways. “It’s kind of like suturing,” he says. “Unfortunately, that tends to not last very long.”

So Lynn hired Jon Cornia, a conservator based in the San Diego area, to fix the problem by cutting through the metal pins and inserting a 3-millimeter-wide slice of wood into that slot and then glueing it together. “And it works perfectly,” Lynn says. He did not want to replace the head joint with a copy, because no matter how well crafted, it would still be different in minute ways: “The original bore would have some irregularities that would get erased when you make a modern head.”

According to the National Music Museum’s Darryl Martin, philosophical approaches to restoration, at least in museums, go through cycles. When he first began working on instruments in the 1980s, there was a strong urge to make them playable. Later attitudes changed to hardly touching them at all. And now the pendulum has swung again toward making instruments playable but doing so in a cautious and measured way.

“That idea that, ‘Here is a perfectly playable instrument — let’s just stick it behind glass and never touch it forever,’ seems a bit weird,” he says. “It’s like a car. You have a 1930s car in running order. Don’t drive it for 10 years and see what happens. It’s not going to work. It’s going to be in worse condition.”

Kyle MacMillan served as the classical music critic for the Denver Post from 2000 through 2011. Now a freelance journalist in Chicago, he’s written for the Chicago Sun-Times, Wall Street Journal, Chamber Music, and Early Music America’s EMAg. He contributes programs notes and essays to the Ravinia Festival and the Colorado Music Festival.