by Solomon Guhl-Miller

Published February 17, 2025

Early Music in the 21st Century, edited by Mimi Mitchell. Oxford University Press. 2024. 320 pages.

What is the future of the early-music movement? The essay collection Early Music in the 21st Century goes a long way toward answering that question. Editor Mimi Mitchell notes “[this volume] introduces new ways to research and think about early music, addresses various performance issues, offers pedagogical possibilities and new technological tools, and – perhaps most importantly in this new century – suggests ways we can engage with the present as well as with the past.” It does this with rigor.

The volume opens with a prologue by Nicholas Kenyon, who places this book in the context of the history of early-music research along with similar collections of the past 40 years. Notably, he cites the set of essays he edited for Early Music in 1984 by Temperley, Leech-Wilkinson, and Taruskin that marked the beginning of the cooling of the fervor which had defined the early-music movement. Despite excellent work by performers and scholars, that fervor has yet to return in force; in its place is the multiplicity of subfields represented in this volume.

The book is divided into five themes. The first, “Methodological Viewpoints,” opens with Caroline Bithell’s “Early Music: Views from Ethnomusicology,” which breaks down three approaches used in early-music performance scholarship: applying contemporaneous theoretical treatises and using original instruments, recreating traditional performance styles from living cultures, and recreating the work through informed improvisation and performance. Bithell highlights how improvisational Georgian polyphony employs all three and allows for more informed improvisation.

Jed Wentz’s essay rejects the now-old-fashioned premise that early music should be performed with minimal added expressivity. Wentz discovered a poem by William Collins (1721-1759) annotated with musical terminology on a word-by-word basis, implying rapid shifts of tempo and emphasis to create a highly expressive reading, a method Wentz believes should be adopted in the interpretation of 18th-century music. In Kai Köpp’s essay, “Interpretations Research,” historical recordings, piano rolls, and text-critical performance notes are used to reconstruct an early 20th-century performance.

The book’s second theme, “(Non) historical Instruments,” begins with Jeremy Montagu’s posthumously published “Making (Faking?) Early Music,” a dose of reality on a par with the dousings of fervor from Kenyon’s collections of essays. Montagu outlines how little we know about playing musical instruments from before the 19th century; much of what is done is between guesswork and “faking.”

In “Plastic Fantastic,” Fiona Brock, Andrew Hughes, and Jeremy Uden discuss how 3D prints of instruments can simulate the sound and experience of playing ancient instruments, many of which are too damaged or fragile to be used. Mimi Mitchell surveys the violin portion of the International Bach Competition in Leipzig after the competition expanded to include Baroque instruments. The selection of winners reflects an openness to the intertwining of Baroque and modern instruments and styles.

The section on “Pedagogical Perspectives” explores extraordinary European early-music educational programs. Kailan Rubinoff covers the separation and then reintegration of the early-music program in the general music program at the Conservatorium van Amsterdam, while Kelly Landerkin and Claire Michon’s essay on the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, in Switzerland, and pôle Aliénor, in France, shows how these schools stress study of theoretical treatises and original instruments as well as informed improvisation. One common element among each of these institutions is robust government support, the lack of which in the U.S. prevents similar programs from appearing. Jonathan Impett’s essay focuses on the link between the present and the past, noting students cannot merely represent the past, while Deanna Pellerano interviews the creators of the online bibliography Inclusive Early Music.

“Transformative Technologies,” the fourth theme, presents research on the cutting edge of sound studies and instrument design. Alon Schab provides a history of the early-music movement’s use of technology, including modifying the sounds of instruments and bringing out “historically informed aspects of their structure and sound.” Hans Fidom explores the Utopa Baroque organ at Orgelpark, which is both a Baroque Hildebrandt-like instrument, and, thanks to magnets attached to each pipe, a new instrument with a dazzling array of features.

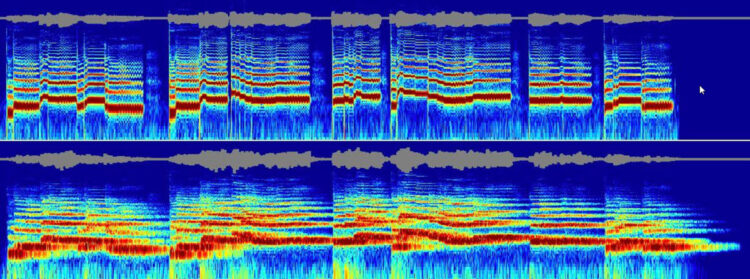

According to Eoin Callery and Jonathan Abel, technology can stimulate a particular sound space, in this case the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Through careful miking and the use of headphones, performers can hear how they would have sounded in a completely different space and adjust their performance in real time.

Finally, “Revisiting History” opens with Robert Ehrlich’s “The New Dutch Recorder Sound of the 1960s”, outlining the pivotal role of Frans Brüggen in this history of recorder performance. Mélodie Michel’s essay is a notable example of how early music is taught in regions outside of Western Europe. Michel notes that in Latin America, “there is a general consensus among performers and scholars that Latin American folk music does have important ties with European Baroque music [that] have had profound consequences on early music performance in the Latin Americas.” This consensus has led to new early-music programs in the region and an excitement unmatched in Western Europe since the 1980s. The volume closes with Caitlin Vincent’s essay on recent opera performances that alter key aspects of works to better reflect the world of today, including a Carmen in which the title character doesn’t die, and performances of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo that include Indian classical music.

Each essay in this collection represents a direction for early-music performers and researchers, making it a valuable tool for graduate students interested in exploring the multiplicity of possibilities in this field. The accompanying website, Early Music in the 21st Century, supplements several chapters with listening examples.

The bibliographical support could be improved. While Blithell cites John A. Graham’s website, his 2015 dissertation would have made a valuable addition to her argument. Daniel Leech-Wilkinson’s online book Challenging Performance could have supported both Köpp’s and Vincent’s essays. Recordings of Brüggen’s recorder playing in the various stages of his development would have been a welcome addition to the accompanying website.

But aside from these minor issues, Early Music in the 21st Century, through excellent scholarship and compelling musical examples on the companion website, admirably succeeds in introducing students to multiple paths forward in early-music research.

Solomon Guhl-Miller is a music historian teaching at Rutgers University. He has published on Medieval music and opera, and is currently lead investigator on the NEH-funded digital humanities project Ars Antiqua Online.