by

Published November 4, 2016

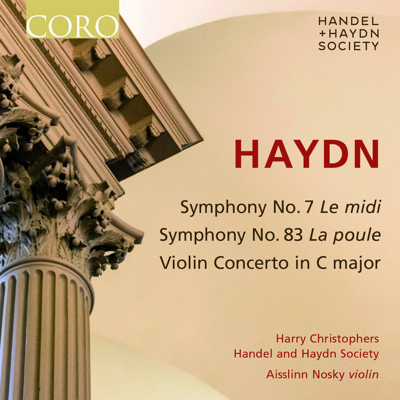

Haydn: Symphonies Nos. 7 and 83, Violin Concerto No. 1

Aisslinn Nosky, violin; Handel and Haydn Society; Harry Christophers, conductor

CORO 16139

By Laurence Vittes

CD REVIEW — These Handel and Haydn Society live concert performances of three key Haydn works from Symphony Hall in Boston in January 2015 are so comprehensively thought out, expertly put together, and commandingly played, it’s as if the Boston Symphony had been reborn playing on 18th-century instruments and modern copies. With artistic director Harry Christophers conducting and Aisslinn Nosky leading the strings and serving as soloist in the Violin Concerto No. 1, the Society may not use the 40 strings for which Le Concert de la Loge Olympique, which commissioned Haydn’s six “Paris” symphonies, was famous. But the Boston ensemble’s 24 have the same audience-pleasing attitude, and they come complete with handmade gut strings and Classical bows to evoke the sounds Haydn himself expected to hear.

The advantages in the second of the “Paris” symphonies are evident; like the others in the set, No. 83 (“The Hen”) can be a bear (pace No. 82, “The Bear”) to move quickly in concert when the conductor might sense a need for more urgency or passion. But here the response is almost instantaneous, the energy hair-raising at times, and usually thrilling. This is a performance of great physical beauty, heightened expressive nuance (including nearly inaudible moments in the slow movement), and carefully chosen speeds: the lines of the Andante are spun out to emphasize its timeless poetry, while the Menuetto and Trio race along at a cheeky reinterpretation of Allegretto.

The advantages in the second of the “Paris” symphonies are evident; like the others in the set, No. 83 (“The Hen”) can be a bear (pace No. 82, “The Bear”) to move quickly in concert when the conductor might sense a need for more urgency or passion. But here the response is almost instantaneous, the energy hair-raising at times, and usually thrilling. This is a performance of great physical beauty, heightened expressive nuance (including nearly inaudible moments in the slow movement), and carefully chosen speeds: the lines of the Andante are spun out to emphasize its timeless poetry, while the Menuetto and Trio race along at a cheeky reinterpretation of Allegretto.

There is no way not to make Haydn’s early Symphony No. 7 (“The Noon”) sound drop-dead gorgeous. And while, at its core, it is still a galant concertante symphony, a performance like this — with the wind and string soloists so confident in the sheer pleasure of their virtuosity — brings out the composer’s emerging sense of structural integrity, over which he would build larger symphonic forms.

Haydn’s concertos never benefited from his mature thinking, but in Nosky’s passionate advocacy, and particularly her technically brilliant, stylistically wide-ranging cadenzas, she gives the Violin Concerto No. 1 a reading of size, charm, and deep affection. Playing her 1746 Spanish instrument with a copy of an early Tourte bow made by Stephen Marvin of Toronto, the orchestra’s Canadian concertmaster takes an approach to Haydn, she wrote in an email, that “is personal rather than based on any concrete historical performance practice.”

In fact, Nosky uses her own cadenzas for all her concerto performances. She believes the cadenza should, in addition to entertaining the listener and heightening the excitement at the end of the movement, “complement the overall arc of the composer’s musical narrative.”

Nosky looked at Mozart’s cadenzas to his piano concertos not for models, but “for examples of what may have been performed in terms of length, scope, and technical difficulty,” she said. Although she plans most of her cadenzas ahead of time, “there are improvisational elements in all of them, especially in regards to tempo and rhetorical space. The cadenzas I compose are more of a harmonic framework within which the smaller elements can change.”

While Nosky’s graceful cadenza in the Adagio flows conventionally, her creation for the Allegro moderato has a spontaneous feel, leading through a series of imaginative episodes to a spectacular final trill.

Laurence Vittes writes regularly about music for The Huffington Post, Gramophone, Bachtrack, Strings, Audiophile Audition, and the Southern California Early Music Society.