by

Published September 29, 2017

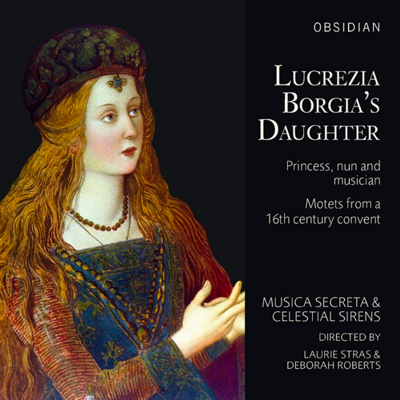

Lucrezia Borgia’s Daughter. Princess, nun and musician: Motets from a 16th century convent

Musica Secreta & Celestial Sirens

Obsidian CD717

By Karen Cook

CD REVIEW — In a typical Renaissance city, the average person might not have had much access to music, at least not high “art” music, as many might conceive of it today. Without sufficient funds or status, people were limited in what they could regularly hear. But what every (Christian) person had access to was the church, and where there were churches, there was music. Especially in a city like Ferrara, churches were everywhere, as were monasteries and convents, which also had their fair share of music. It might be a surprise to some, but nuns were active singers, even composers, of Renaissance polyphony. And yet, due to the nuns’ religious position and also their gender, at least some of this music goes uncredited.

Enter Laurie Stras. In a sort of musicological Indiana Jones moment, Stras came across a book of motets published by Girolamo Scotto in 1543. The motets are anonymous and, moreover, written for equal voices (i.e., within a two-octave range). As Stras worked on a performing edition, she began to realize how well written they were, full of dissonant clashes reminiscent of Tallis or Gombert, exploring free imitation in a time when to do so for five voices was fairly novel. But the publisher did not name any composer. Stras’s study of the motets revealed textual clues that led to a likely point of origin: the monastery of Corpus Domini in Ferrara. Furthermore, other musical and textual references suggested to Stras a possible composer: Eleonora d’Este (1515-75).

Enter Laurie Stras. In a sort of musicological Indiana Jones moment, Stras came across a book of motets published by Girolamo Scotto in 1543. The motets are anonymous and, moreover, written for equal voices (i.e., within a two-octave range). As Stras worked on a performing edition, she began to realize how well written they were, full of dissonant clashes reminiscent of Tallis or Gombert, exploring free imitation in a time when to do so for five voices was fairly novel. But the publisher did not name any composer. Stras’s study of the motets revealed textual clues that led to a likely point of origin: the monastery of Corpus Domini in Ferrara. Furthermore, other musical and textual references suggested to Stras a possible composer: Eleonora d’Este (1515-75).

Eleonora spent almost her entire life in that monastery; after her mother, the infamous Lucrezia Borgia, died when she was 4, she was sent there, and at 8 she proclaimed that she wished to become a nun. By 18, she was the abbess. The entire Este family comprised music lovers, many also virtuoso performers and composers; Leonora was her mother’s daughter in that regard. As not only a nun and a woman, but also a noble to boot, it is possible that she composed the works but wanted to keep her identity hidden. Such is Stras’s hunch, and a convincing one at that.

Sixteen of the motets are recorded on this album. Musica Secreta and Celestial Sirens use a variety of voice combinations, along with organ and gamba, which a convent would have employed to reinforce or provide lines lower than the range of the voices they had at hand. Of particular note is the choice to feature women of different ages to better reflect a convent’s typical personnel.

The album is, in a word, compelling. Despite the contrasts in range and texture, moving from full group to soloists, instruments or no, the recording feels not timeless but out of time, mesmerizing in the constant wash of imitative lines and the gentle rise and fall of each individual voice. The little dissonances Stras mentioned surprise as well as uplift. “Sicut lilium inter spinas” is a tiny, perfect gem, whereas the lengthier pieces, like “Angelus Domini descendit,” seem to reinvent themselves every minute or so — here imitating bells, there borrowing a chant or even a singing exercise. It’s an album as beautifully performed as it is researched, and one can only hope that more “anonymous” works get such attention.

Karen Cook specializes in the music, theory, and notation of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. She is assistant professor of music at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.