by

Published February 16, 2018

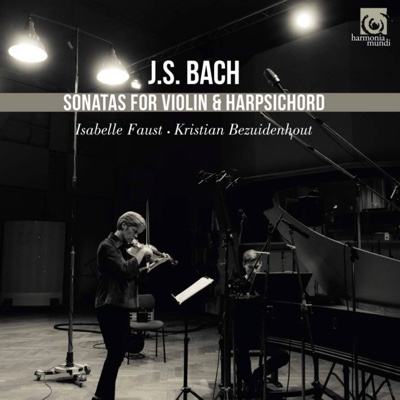

J. S. Bach Sonatas for Violin & Harpsichord

Isabelle Faust, violin; Kristian Bezuidenhout, harpsichord

harmonia mundi 90225657

By Daniel Hathaway

CD REVIEW — This extraordinary album presents all six of Johann Sebastian Bach’s sonatas for violin and obbligato harpsichord in compelling performances by Isabelle Faust and Kristian Bezuidenhout.

Like Bach’s flute sonatas (BWV 1030-1032), viola da gamba sonatas (BWV 1027-1029), and organ sonatas (BWV 525-530), the six violin sonatas (BWV 1014-1019) are written as trios for two performers (or three, if you decide to double the left hand with a cello or gamba). As Peter Wollny writes in his liner notes, “During the first half of the eighteenth century, the trio texture was elevated to the status of a compositional ideal, since it appeared to achieve a perfect synthesis of linear counterpoint, full-sounding harmony and cantabile melody.”

Like Bach’s flute sonatas (BWV 1030-1032), viola da gamba sonatas (BWV 1027-1029), and organ sonatas (BWV 525-530), the six violin sonatas (BWV 1014-1019) are written as trios for two performers (or three, if you decide to double the left hand with a cello or gamba). As Peter Wollny writes in his liner notes, “During the first half of the eighteenth century, the trio texture was elevated to the status of a compositional ideal, since it appeared to achieve a perfect synthesis of linear counterpoint, full-sounding harmony and cantabile melody.”

That technique, so highly perfected by Bach, made for durable music that survived the great stylistic changes of the later eighteenth century. Referring to these six sonatas in 1774, C. P. E. Bach wrote, “They still sound very good now…even though they are over fifty years old.”

They continued to sound very good to later ears. One way to debunk the persistent notion that J. S. Bach’s music passed into oblivion soon after his death is to follow the continuing history of the violin sonatas. Handwritten copies made their way to Berlin, then via Austrian ambassador Baron van Swieten to Vienna, then on to Paris. The first printed score came off the presses in Zurich in the early 1800s along with the B Minor Mass, and Ferdinand David and Felix Mendelssohn performed at least one of the sonatas at the Gewandhaus in 1840. Samuel Wesley championed them during the “English Bach Awakening,” and Franz Liszt arranged a movement of BWV 1017 for organ in 1866.

Most probably written during Bach’s tenure as Capellmeister to prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen from 1717-1723, but fussed over from time to time until the end of the composer’s life, the six violin and obbligato harpsichord sonatas vary considerably in layout and musical style.

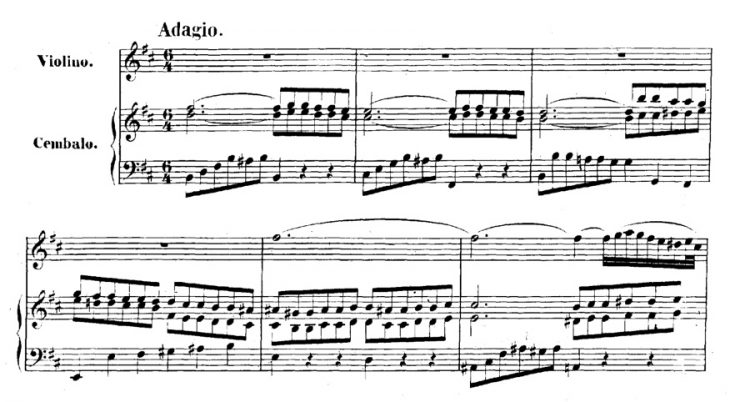

The opening Adagio of the B Minor Sonata, BWV 1014, catches Bach, Faust, and Bezuidenhout in one of their finest moments. Bach writes sighing motives for the harpsichord in thirds and sixths, and after the violin sneaks in almost imperceptibly on a long note, composer and performers collude to create malleable, expressive music that stops just short of rhythmic distortion.

While Faust and Bezuidenhout play with easy virtuosity even at daredevil tempos, it is their penetrating interpretations of slow movements that really stand out. Writing about his father’s Adagios, C. P. E. Bach had to admit that “one could not compose in a more melodious fashion today.” As an example, the Siciliano of the C Minor Sonata is a close cousin to “Erbarme dich” in St. Matthew Passion, and Faust and Bezuidenhout make it tug at the heart-strings, even without benefit of the human voice.

Recorded over the period of a week in August 2016 at Teldex Studio Berlin, the disc makes use of a John Phillips harpsichord after a 1722 instrument by Johann Heinrich Gräbner, a large, German-style instrument borrowed from Trevor Pinnock that speaks with warm, colorful clarity and stands up handsomely to the violin.

Anyone who has performed Bach’s trio-textured works will attest to the high level of technical ability and mental concentration they require. That Faust and Bezuidenhout can make them sound so effortlessly musical is a remarkable accomplishment. This album is a must for every Bach lover’s collection.

Daniel Hathaway founded ClevelandClassical.com after three decades as music director at Cleveland’s Trinity Cathedral. He studied historical musicology at Harvard College and Princeton University, and orchestral conducting at Tanglewood, and team-teaches Music Criticism at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music.