by

Published March 2, 2018

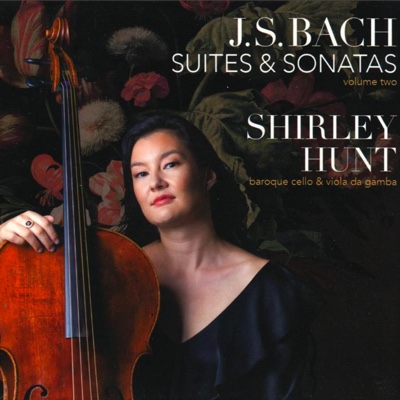

J. S. Bach: Suites & Sonatas, Volume Two

Shirley Hunt, baroque cello, viola da gamba; Ian Pritchard, harpsichord

Letterbox Arts LA 1002

By Benjamin Dunham

CD REVIEW — In general, the strength of Bach the composer imposes itself on all performances of his music. Bach is still Bach whether performed with large forces or one-to-a-part, with modern or historical instruments, whatever the approach of the performer. Bach’s cello suites, however, seem like a tabula rasa on which the personality of performer is “writ large,” and this is so beginning with the recordings of Pablo Casals up to cellists of today, including performances on both modern and period instruments.

The result is that the boat to my desert island might sink with all the wonderful cellists I’d want to bring with me: Casals, Pierre Fournier, Jacqueline du Pré, Anner Bylsma, Yo-Yo Ma, Pieter Wispelwey, Christophe Coin, and now Shirley Hunt. Her series, J. S. Bach Suites and Sonatas, has issued Volume Two with the cello suites Nos. 2 in D minor, BWV 1008, and 5 in C minor, BWV 1011, along with the Sonata for Viola da Gamba and Harpsichord No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1027. These are certainly performances I would want to keep aboard.

The result is that the boat to my desert island might sink with all the wonderful cellists I’d want to bring with me: Casals, Pierre Fournier, Jacqueline du Pré, Anner Bylsma, Yo-Yo Ma, Pieter Wispelwey, Christophe Coin, and now Shirley Hunt. Her series, J. S. Bach Suites and Sonatas, has issued Volume Two with the cello suites Nos. 2 in D minor, BWV 1008, and 5 in C minor, BWV 1011, along with the Sonata for Viola da Gamba and Harpsichord No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1027. These are certainly performances I would want to keep aboard.

The cello suites are thought to have been composed at the end of the second decade of the 18th century during Bach’s time at the court in Cöthen, when he produced so much secular instrumental music. They are associated with his Sonatas and Partitas for Violin, BWV 1001-1006, as glorious examples of sleight-of-hand polyphony achieved on what are, essentially, monophonic instruments.

In the Summer 2014 EMAg, Tom Moore reviewed Volume One of this series as “a fine debut and one with promise for future projects,” a promise this recording helps to fulfill. (Volume Three is scheduled for release later this year with a complete set of program notes for all volumes.)

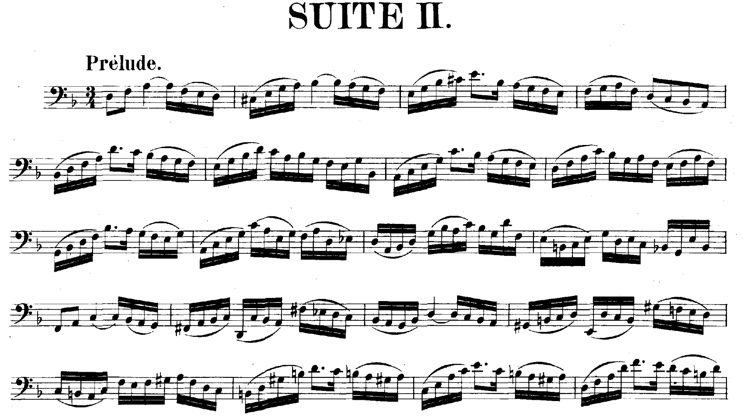

As the opening bars of the Prelude of Suite No. 2 unfold, Hunt savors each high point without rushing, as if she is waiting for Bach to invent a new phrase. The effect is to emphasize the spontaneity of the music, without organizing the notes into a predetermined narrative. And that spontaneity is carried through to the last four chords, which are turned into a quasi-cadenza that feels exactly right.

After a conversational Allemande, Hunt contrasts a breathless Courante with a languid Sarabande, a nostalgic memory of a dance, perhaps, not the dance itself. The minuets have all the needed weighting, and the Gigue has brio galore. Throughout, Hunt’s 1775 William Forster Sr. cello is recorded in a natural, forward acoustic.

BWV 1027 is a later work, from the 1730s, evidently adapted from his Trio Sonata for Two Flutes, BWV 1039, with the first flute part appropriated by the right hand of the keyboard player. The give-away is the harpsichord’s long opening note, which must be trilled to sustain it. This sounds so natural unadorned in the flute version (even on performances of BWV 1027 with organ accompaniment). Hunt’s 1993 John Pringle gamba sounds perfectly luscious, and harpsichordist Ian Pritchard is an able partner on an Earl Russell instrument modeled on the 1734 Henri Hemsch in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. But after enjoying the cadenza at the end of the Suite No. 2 Prelude, I was hoping for a connecting flourish in the awkward pause before the last two chords of the opening Adagio, from either or both instruments.

In the Suite No. 5 in C Minor, the deep resonance of Hunt’s cello is brought out in sympathetic scordatura tuning. Hunt again gives the opening Prelude, described as a French overture, an improvisatory flavor, as if each section had been discovered on the spot. The following fugal movement in 3/8 leads to an Allemande in dotted rhythms that sounds a lot like the return of the French overture in the standard pattern. An agitated Courante leads to the ineffable Sarabande, which is movingly played. (The disc is dedicated to the memory of Hunt’s sister, mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt Lieberson.) After this heartfelt expression of sorrow, the concluding gavottes and gigue have swagger and sass — and serve to restore a welcome sense of optimism.

Former EMAg editor Benjamin Dunham has reviewed recordings and concerts for The Washington Post, Musical America, American Recorder, and GateHouse Media.