By Anne E. Johnson

Jeremy Rhizor, founder of the Academy of Sacred Drama, is a man with a mission. Okay, several missions. The violinist-conductor wants to save forgotten early-music pieces from obscurity, enhance the social and intellectual aspects of early performance, encourage independent scholarship, and make early-music research available freely and publicly.

In trying to reach those goals, Rhizor finds unknown repertoire — much of it has never been performed in the modern day — and gives the music and text new editions and translations as well as live performances. It’s a team effort. “The Academy,” Rhizor was quick to point out in a phone interview, “is not a performance ensemble of freelance early-music people, but a membership organization. Most of what we perform is put together by a roster of our professional members: musicians, translators, academics, and independent scholars.” There are also paid memberships open to the general public.

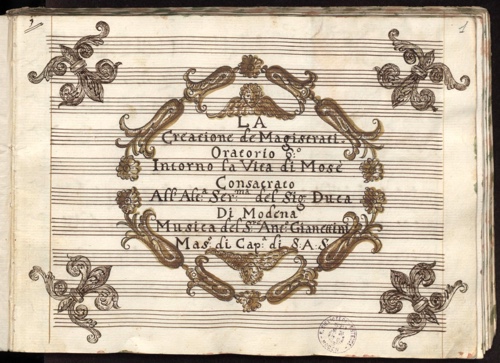

Now in its second year of performances, the ASD focuses on a theme each season. Last year the theme was Judith (of the Old Testament). The 2018-19 season has been styled “The Year of Moses.” To that end, Rhizor has found three oratorios and an evening’s worth of cantatas celebrating the man who parted the Red Sea. One of those oratorios, Giovanni Antonio Gianettini’s La creatione de’ magistrate, will be performed Jan. 13 at Corpus Christi Church in Manhattan.

Never heard of Gianettini? You’re not alone. “I had to Google him,” admitted Louise Basbas, founder and executive director of the concert series Music Before 1800, which is presenting the program. “But I trust Jeremy’s judgment. He’s been digging up some really interesting stuff.”

For the record, Gianettini (1648-1721, and sometimes spelled Giannettini or Zanettini) was trained in Venice and worked at San Marco and Santi Giovanni e Paolo as a composer, singer, and organist until 1686. Then he was named maestro di cappella to the Duke of Modena, where (the article in Grove points out) he received an unusually high salary for his work composing and performing secular and sacred music. As Rhizor put it, “Modena was an extremely well-funded court.”

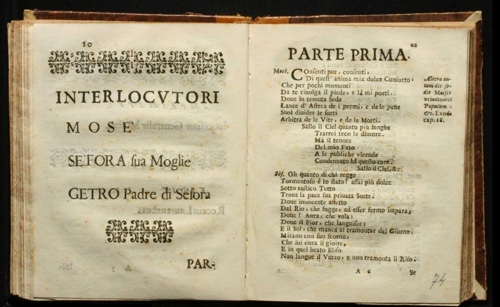

It wasn’t specifically Gianettini that drew Rhizor to the piece, however, but the fact that this is part of a cycle of Moses oratorios with librettos by Giovanni Battista Giardini (b. 1650), who also worked for the Duke of Modena. “Giardini wrote eight of these oratorios in all,” Rhizor said, “each exploring different aspects of Moses’ character.” Six composers collaborated with Giardini on this project, the ones best known today being Vincenzo De Grandis (whose Giardini-penned Il Nascimento di Mosè the ASD performed in September), Giovanni Paolo Colonna, and Bernardo Pasquini (whose I Fatti di Mosè nel deserto is on tap for April).

For La Creatione de’ magistrate, Giardini invented scenes in Moses’ life, taking inspiration from a passage in Exodus. “He imagines dialogue between Moses and his wife,” said Rhizor, “as well as advice from Moses’ father-in-law.” Much of the text is political in nature, and “more reflective of the current government of Modena than the time of Exodus.” More importantly for Rhizor, the political commentary is also relevant to the present day. “Giardini is giving general advice on what is good governance. I have the desire to be able not just to produce concerts, but also to have engagement to make our own lives in society better.”

As for the music itself, Gianettini requires very few participants. The performance at Corpus Christi will use only three singers (countertenor Daniel Moody as Mosè, soprano Sara MacKimmie Tomlin as his wife, Sephora, and bass-baritone Peter Walker as the father-in-law, Getro). There is no separate chorus. “Unlike in French oratorios of the time, Italian oratorios usually just use the soloists as the chorus,” said Rhizor. “But here there are really too few soloists to call it a chorus. It’s just arias, duets, and trios.”

The performance will include seven instrumentalists in a configuration Rhizor characterizes as basically trio sonata with viola, as is typical of many of the oratorios in Giardini’s cycle.

Besides the small cast, Rhizor pointed out another feature in Gianettini’s score that he found especially intriguing. “There is a common practice in performing late 17th-century oratorios where the performers elided the different sections to keep the music flowing.” The technique of moving directly from one section to another was not notated, but was a performance convention, and one that is commonly in use today among HIP practitioners. “But in the case of the Gianettini, he’s done something very unusual: He has meticulously composed the elisions instead of just assuming they will be done.”

This is not just some fanciful theory of Rhizor’s. In fact, he says, Gianettini uses two different notational methods to force players to connect the sections seamlessly. The first is a symbol. “At the end of an aria, you’ll find a funny squiggly sign in the bass. That indicates that that music will overlap with the following section.” Gianettini also takes advantage of score alignment for this purpose. “Sometimes he will write it out literally, so that the new instrumental line starts directly underneath the last measure of the aria’s vocal line.”

Of course, this is the kind of detail that early-music scholars drool over, and Rhizor is determined to go out of his way to share such gems with anyone who is interested. For one thing, the ASD plans to produce new editions and translations of the works they perform. These will be published online under an open Creative Commons license that, according to the ASD website, “enables interested parties to share and modify the work of Academy transcribers and translators when the transcribers, translators, and the Academy are appropriately credited.” The edition of the Gianettini, as yet unpublished, is by Rhizor and Leili Zhang, based on a 1688 manuscript.

There is also an Academy Journal — freely available on the website in the form of a blog — where academic and independent scholars can offer articles about music related to a particular season. During “The Year of Judith,” for example, religion and philosophy expert Mary Elliot wrote about how that character embodies the concepts of beauty and understanding.

Producing the journal is labor-intensive, and Rhizor admits it has not yet garnered the response he was envisioning. “Our hope is to be able to create a world people can read about. Audiences don’t know the stories of the oratorios anymore. It used to be that they would have known and had an opinion on whatever variation of the story they were seeing in an oratorio. These were stories they knew intimately and well.”

The shared experience and opportunity for analysis are also important elements of Rhizor’s performances. “The oratorio was never meant to be a concert piece that you just listened to. You would expect a sermon in the middle, or a reception afterward, or both. It gives you another aspect of the experience. It’s not something that’s extra, but part of the original structure. In today’s world it seems like innovation, but the 17th-century audience would have expected an oratorio to be not only a musical experience but also an intellectual and social one.”

To fulfill the intellectual obligation, Rhizor has invited independent scholar Alice Jarrard to give a lecture halfway through the 90 minutes of music on Jan. 13. She is the author of the book Architecture as Performance in Seventeenth-Century Europe: Court Ritual in Modena, Rome, and Paris. As for reconstructing an authentic social experience? There will be dessert served after the performance at a reception for the audience and performers.

It’s a fascinating endeavor in every respect, but admittedly esoteric and perhaps a lot to ask of concertgoers. “We’ve been at this for less than two years, and we are just trying out these things,” said Rhizor. “But we have to try and, in some ways, fail in order to reach our goals.”

Fortunately for the ASD, Rhizor has a stalwart backer in Basbas, and she’s willing to let Music Before 1800 take risks on his behalf. “The Academy of Sacred Drama is a special and unusual institution,” she said. “Jeremy is so generous in wanting to involve people in his projects. I know what it’s like to try to keep an early-music organization going, so I want to do more for him than just cheer from the sidelines if I can help in some way.”

Anne E. Johnson is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn. Her arts journalism has appeared in The New York Times, Classical Voice North America, Chicago On the Aisle, and Copper: The Journal of Music and Audio. For many years she taught music history and theory in the Extension Division of Mannes School of Music.