By Brett Kostrzewski

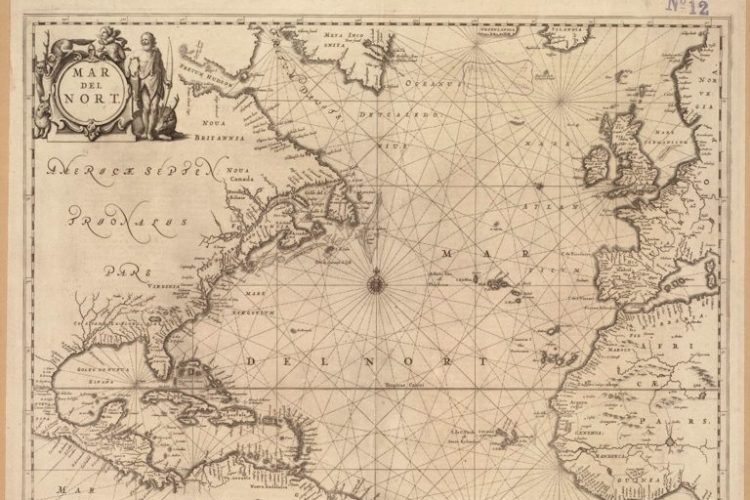

Few events in global history have been more consequential than Christopher Columbus’s 1492 voyage across the Atlantic. And yet, musicology and performance are only recently recognizing the importance of the subsequent cultural exchange for musical developments both in Europe and what would become the Americas.

Boston University’s Center for Early Music Studies (CEMS) seeks to make a sizable step forward in this area with a conference, “Atlantic Crossings: Music from 1492 through the Long Eighteenth Century,” which will be held June 7 and 8 at the Rajen Kilachand Center for Integrated Life Sciences & Engineering. As stated in the call for papers, the conference aims to correct what has been a lack of adequate exploration of the “repercussions for music and musical practices on both sides of the Atlantic.” Scholars from the United States, United Kingdom, Colombia, Chile, Portugal, and Spain will present research on topics that address the exchange of music, culture, and performance that accompanied Europe’s arrival in the New World. The conference is being organized and directed by Victor Coelho, CEMS director and chair of BU’s Department of Musicology and Ethnomusicology.

Benjamín Juárez, professor of musicology at Boston University as well as the recently appointed director of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México – Boston (housed at University of Massachusetts Boston), sees 2019 as the ideal time to hold such a conference. Despite the undeniable importance of Spain in the early modern period, the so-called Black Legend — the result of anti-Hispanic histories propagated largely by English and German scholars beginning in the 16th century — has dampened scholarly research of Spain across academic disciplines.

“Neutral musicology,” Juárez says, “has focused on Italy and other parts of Europe, while only a few have taken on Spain and Latin America, risking their careers.” He notes that Robert Stevenson (1916-2012), an early advocate of musicological study of Spain and the New World, was at one time forbidden by his dean to teach the music of Mexico because it was “only mariachi music.”

The climate has improved drastically since then, but the “Atlantic Crossings” conference identifies many themes that remain underserved by scholars. Slavery is a particular focus, both in the call for papers and the resulting program. Scholars will address the musical experience of slaves and the degree to which the slave trade — a triangle between Europe, Africa, and the Americas — created an unprecedented circulation and integration of musical styles from the peoples of each continent.

“Music is a two-way street,” says Juárez.

Too often, scholars in the Western academy have identified the transmission streams from Europe to the New World and ignored the movement in other directions — not just from the New World to Europe, but also between Africa and both continents. The musical traditions that continued within these communities after this exchange began also merit further study. As Juárez points out, “The last place a cornetto was played was in Puebla Cathedral, long after its extinction in the Old World.”

The success of the call for papers for the conference and the resulting program reveal the interest in this complex and fraught area, even as its acceptance in the academy has only recently increased. Papers at the conference will address such topics as the brutal forms of musical torture carried out on slave ships; musical expression of the indigenous peoples of the Canary Islands; and the transatlantic timber trade’s impact on instrument construction.

The conference also encourages renewed interest in the breadth of original source material that can be found in Latin America’s cathedrals and archives. A rare set of microfilms containing the musical sources preserved at the cathedrals of Mexico City and Puebla is on long-term loan to Boston University, thanks largely to the efforts of Juárez. Scholars from other parts of the United States have already made use of this important collection, and it will figure prominently in a panel at the conference.

The importance of the conference extends beyond matters of musicology and underrepresented histories. “This conference puts the spotlight on a new generation of young musicologists researching the music, traditions, performance, and archives of Mexico and Latin America with fresh eyes, on the same level as young musicologists studying the standard repertoire,” says Juárez.

One such scholar presenting at the conference is Brian Barone, a Ph.D. candidate at Boston University also serving as an organizer. “Because my dissertation is an attempt to theorize the musical consequences or facets of what scholars in other disciplines have described as the ‘Atlantic world,’ I’m especially glad that so many researchers have shown an interest in thinking together about this period of intense importance to world history — one whose consequences we’re still living today,” he says.

Barone is also excited about the mix of what could be described as “old” and “new” questions within the conference: “We’ll be vigorously taking up issues often sidelined in historical studies of music — slavery, imperialism, race, and indigeneity, for example — while also seeking new perspectives on perennial interests — polyphony, opera, reception studies, and more.” He points out that papers address understudied topics with rich source material, such as the cathedral repertoire of colonial Latin America, as well as topics difficult to study because of a lack of sources, such as the oral musics of the African diaspora.

In so doing, the conference seeks to break down the institutional and historiographical barriers that have discouraged mainstream scholarship from encountering the tough questions posed by these topics. “Atlantic Crossings” also challenges the rise of a new nationalist politics that delineates history and culture by the anachronistic borders of the 21st-century West.

The conference marks an important milestone for the Center for Early Music Studies, which seeks to foster constant dialogue between early music scholarship and performance. While the center has typically focused on the “standard” early music repertoire — ranging from medieval polyphony to Heinrich Schütz — “Atlantic Crossings” makes a strong statement in placing these underrepresented musics and musicians alongside their better-represented contemporaries. As Barone puts it, “to rethink the priorities, methods, and geographies that come to mind when we think about this thing called ‘early music.’”

Musicology has long recognized the importance of networks and the flow of music and culture as facilitated by itinerant musicians. But only recently have the narratives of transatlantic networks gained significant currency in the musicological academy. “Atlantic Crossings” exemplifies the first fruits of institutional support to investigate these narratives.

For more information about “Atlantic Crossings” and the Center for Early Music Studies, visit www.bu.edu/earlymusic.

Brett Kostrzewski is a Ph.D. candidate in historical musicology at Boston University.