by Karen Cook

Published January 6, 2020

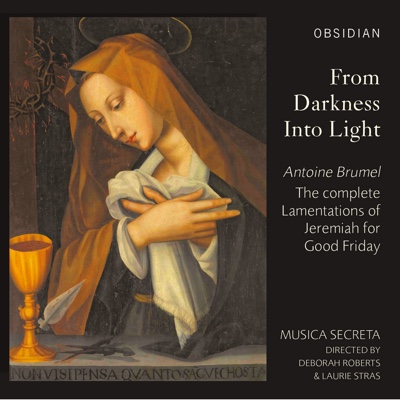

From Darkness Into Light: The Complete Lamentations for Good Friday of Antoine Brumel. Musica Secreta. Obsidian CD719

For internationally acclaimed musicologist Laurie Stras, it was just another day in Florence — until it wasn’t. Leafing through a large, well-preserved music manuscript (called P.M.), she took pictures of any interesting musical and artistic details. When she revisited her images, what she found was astonishing. In one section of the manuscript, she recognized the refrain “Ierusalem, convertere” of the two known verses of the Lamentations of Jeremiah attributed to Antoine Brumel. But the same refrain was copied again, some 35 pages later. Moreover, the material on these additional pages shares with Brumel’s known verses not just this refrain but also a number of recurring musical motives. Stras thus realized that this manuscript quite plausibly held the entirety of Brumel’s Lamentations. (The Musica Secreta website contains a brilliant analytical guide of the work and further information on its discovery.)

Stras notes that Brumel based his setting on the common Roman Lamentations tone used during services. However, since his setting has five refrains instead of the typical three, this work could not have been used liturgically, but was perhaps intended instead for private devotion. In fact, Stras suggests an origin in the flagellant confraternity of the Buca di San Paolo, which held elaborate feasts and theatrical performances for Maundy Thursday.

Stras notes that Brumel based his setting on the common Roman Lamentations tone used during services. However, since his setting has five refrains instead of the typical three, this work could not have been used liturgically, but was perhaps intended instead for private devotion. In fact, Stras suggests an origin in the flagellant confraternity of the Buca di San Paolo, which held elaborate feasts and theatrical performances for Maundy Thursday.

While so many of the works in the P.M. manuscript are anonymous, its copyist is not: Antonio Moro also compiled the Biffoli-Sostegni manuscript for a Florentine convent, and the two manuscripts share certain features, such as the predominance of equal voices. Therefore, given that nun musicians in convents routinely transposed existing works to suit their particular vocal ranges, and/or access to bass-range instruments such as the organ, sackbut, or viol, the Lamentations have also been transposed to suit this ensemble. Accompanying the premiere of the complete Brumel Lamentations here are several works from the Biffoli-Sostegni manuscript: Moro’s own Sancta Maria succurre miseris, and motets by Josquin, Loyset Compère, and other unnamed composers.

For anyone unfamiliar with earlier recordings by Musica Secreta, hearing such polyphony performed by an all-upper-voice ensemble (plus organ and viol) may be striking at first; however, the music soon sounds as though it were written with this kind of group in mind. Their balance, shaping of individual lines, attention to form and structure, and sensitivity to the text and its meanings all permeate the recording. The Lamentations, in particular, are offered with what might best be described as awe, an awareness of the momentousness of being the first modern ensemble to perform the work in its entirety. Their sheer love for this music is palpable, and it cannot help but stir something deep within the listener.

If just for the importance of the premiere of Brumel’s complete Lamentations, this recording would be practically an imperative. But it is so much more than that — a window into a world of musical practice, not just by nuns but also by the myriad members of a society in which convents played such a pivotal role, and it is performed beautifully.

Karen Cook specializes in the music, theory, and notation of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. She is assistant professor of music at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.