by Aaron Keebaugh

Published October 19, 2020

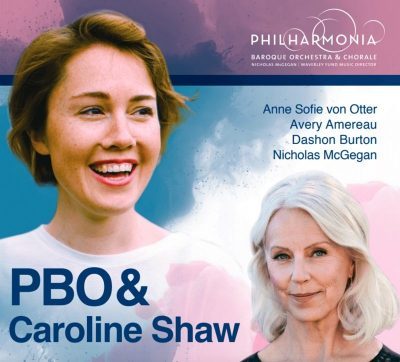

Caroline Shaw: Is A Rose; The Listeners. Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra and Chorale; Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Avery Amereau, contralto; Dashon Burton, bass-baritone; Nicholas McGegan, conductor. PBP-12

Viewed from deep space, the Earth appears as a pale blue dot, a place where human experiences fade into the vastness of the universe. Yet composer Caroline Shaw and Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra paint a portrait of hope in the midst of such immensity.

Composed for PBO, The Listeners is the young composer’s first large-scale composition. The oratorio recalls Handel’s works in the genre scored for soloists, chorus, and period-instrument orchestra. Shaw may be the ideal living composer to write for such forces. Her music — particularly her Pulitzer Prize-winning Partita for 8 Voices — draws upon Baroque forms. She then fills these well-known structures with unusual sonic and vocal choices that often make for daring modernist experiments.

The Listeners may lack the adventurous sounds of the Partita, yet Shaw still makes this 30-minute score an enriching musical experience. She conceived of the work while thinking about the Golden Record, a kind of cosmic LP launched into space aboard the Voyager craft in 1977. It records pictures of animals and humans, greetings in 55 languages, and musical examples ranging from Bach to Chuck Berry. But the heart of The Listeners is Carl Sagan’s 1994 lecture that shows our world as a small and seemingly insignificant place.

The Listeners may lack the adventurous sounds of the Partita, yet Shaw still makes this 30-minute score an enriching musical experience. She conceived of the work while thinking about the Golden Record, a kind of cosmic LP launched into space aboard the Voyager craft in 1977. It records pictures of animals and humans, greetings in 55 languages, and musical examples ranging from Bach to Chuck Berry. But the heart of The Listeners is Carl Sagan’s 1994 lecture that shows our world as a small and seemingly insignificant place.

This live recording, conducted by music director laureate Nicholas McGegan, makes palpable Shaw’s senses of awe, futility, and ultimate optimism. The work brings together poems by such diverse voices as Walt Whitman, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Yesenia Montilla, Lucille Clifton, and William Drummond of Hawthornden. Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra and Chorale bring vitality to the outer movements, which are built upon a single word, “Brillas.” Bass-baritone Dashon Burton’s resonant voice expresses the wonder within Whitman’s verse in “Let your soul stand cool.”

“Greeting” features a snippet from the Golden Record as the orchestra supports each recorded welcome with the warm, supple sounds that could easily fit a film score. Avery Amereau’s rich contralto captures the troubling emotions that emerge when staring into the void. The feeling fades in “Of a million million,” a haunting recitative sung by Burton that ponders the meaning of human experience.

“Maps,” set to Montilla’s text, takes on political overtones, and Shaw’s radiant harmonies convey a utopian dream of borderless societies less concerned with material acquisition. “Sail through this to that,” featuring the smooth-toned chorus, offers another moment of calm but little resolution.

“Pulsar,” scored for orchestra alone, injects energy through driving ostinatos and wild, metrical shifts that recall Philip Glass. But in essence Shaw’s music is a sort of abstracted romanticism, where harmonic progressions, stripped of melody, still capture poignant emotions.

The disc opens with three orchestral songs Shaw wrote for mezzo-soprano Anne Sofie von Otter. Is A Rose muses upon fleeting beauty and loss; von Otter’s dark voice casts each with the inviting joy of a love song. Shaw’s declamatory vocal writing allows for lyrical moments, with “And So” unfolding like an aria. The orchestra supports von Otter with lush tones in “Red, Red Rose,” a setting of Robert Burns’s familiar poem. “The Edge,” based on a text by Jacob Polley, showcases von Otter in arching melodies.

Throughout, McGegan leads vibrant readings that allow the details of these works to flower. The musicians of Philharmonia Baroque find a grace and elegance familiar from their recordings of Baroque repertoire. Shaw’s music, as revealed here, is a deft mix of old sounds and new styles.

Aaron Keebaugh has written for The Musical Times, Corymbus, and The Classical Review, for which he serves as Boston critic. He teaches courses in music and history at North Shore Community College in Danvers, MA.