by Andrew J. Sammut

Published November 2, 2020

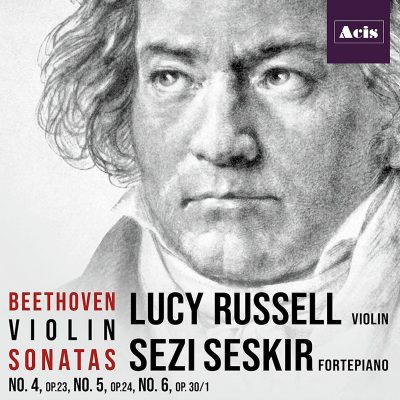

Beethoven: Violin Sonatas Nos. 4, 5, and 6. Lucy Russell, violin; Sezi Seskir, fortepiano. Acis APL29582

Violinist Lucy Russell has amassed an extensive discography as a soloist and as leader of the Fitzwilliam String Quartet. Fortepianist Sezi Seskir performs regularly and is an active scholar and speaker, but this seems to be her first recording. Both musicians describe themselves as “at home” with modern and historical instruments in a wide range of repertoire. Their collaborations go back at least to 2016. For Russell and Seskir’s recorded premiere as a duo, they have selected three works from the mere 10 that Beethoven created for this instrumental combination.

Beethoven assigned the music “to fortepiano and a violin.” Note that order. At the time, sonatas for solo violin with accompaniment were passé. Sonatas for keyboard with an accompanying instrument were the big sellers, but Beethoven goes a step further and often makes both instruments true partners. The intense Sonata No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 23, and the calmer Sonata No. 5 in F major, Op. 24, were meant to be published as a complementary set if not for the vagaries of the printing business at the time. The Sonata No. 6 in A major, Op. 30/1, may be the most experimental of the set, but all three pieces show Beethoven expanding the formal and expressive possibilities of this instrumental pairing. They’re filled with stormy episodes, long-breathed melodies, unexpected thematic variations, and novel contrapuntal developments.

Beethoven assigned the music “to fortepiano and a violin.” Note that order. At the time, sonatas for solo violin with accompaniment were passé. Sonatas for keyboard with an accompanying instrument were the big sellers, but Beethoven goes a step further and often makes both instruments true partners. The intense Sonata No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 23, and the calmer Sonata No. 5 in F major, Op. 24, were meant to be published as a complementary set if not for the vagaries of the printing business at the time. The Sonata No. 6 in A major, Op. 30/1, may be the most experimental of the set, but all three pieces show Beethoven expanding the formal and expressive possibilities of this instrumental pairing. They’re filled with stormy episodes, long-breathed melodies, unexpected thematic variations, and novel contrapuntal developments.

Beethoven was already an established keyboard virtuoso in Vienna and would complete his first symphony roughly a year after composing these sonatas in 1801/1802. They are sometimes smoothed back into Galant prettiness or mannered right into Romanticism. With Russell and Seskir, shapely but uncluttered phrasing and well-set tempos make for a refreshingly gutsy approach. Take the short, mercurial Scherzo of Sonata 5. Elsewhere, it can sometimes just coast on a steady pulse and glib but overly refined statements. This duo still displays plenty of humor, but their attack and tense pacing create an invigorating sense of discombobulation.

Russell and Seskir also craft well-defined rhythmic profiles. They choreograph the tarantella in the opening Presto of Sonata 4 into an addictive and slightly ominous swagger. The succeeding Andante is slower and more inquisitive, but crisp articulation leads to assertive questions. Some listeners may be used to much more vibrato and rubato, but Russell and Seskir offer a welcome reprieve from sentimentalism. It’s easy to speak of them in concert: They obviously know this music and each other well and always come across as a united front.

Coupled with their immediacy of energy and emotion, the two players also highlight the earthy beauty of their instruments. Russell’s Ferdinand Gagliano violin reveals a range of timbres, from a patina coating the piano in Sonata 6’s opening Allegro to spindly accents spurring it along in Sonata 4’s closing Allegro Molto. The disc’s notes point out that Russell plays on open D, A, and E strings to “bring out the contrasted vulnerability and robustness of Beethoven’s sound world.” Sonata 5’s “Spring” first movement is a great place to hear what she means: Each turn in the gentle theme reveals a new color.

Seskir’s playing in that movement’s second subject is also a welcome opportunity to appreciate the transparent depth and bright lines of the Johann Schanz fortepiano built by Thomas and Barbara Wolf. Its big, stalking bass notes create a unique texture next to the violin and piano right-hand ascents. Seskir’s rolling trills and tremolos come across especially warm and even on this instrument.

The acoustical balance places both voices side by side, fitting the music and this partnership. Extensive liner notes by Nicholas Mathew guide the listener through each movement. Unsurprisingly, there are far more recordings of these works on modern instruments than period instruments, but this is an engaging account regardless of such tallies.

Andrew J. Sammut has written about Baroque music and hot jazz for All About Jazz, Boston Classical Review, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, Early Music America, the IAJRC Journal, and his own blog. He also works as a freelance copy editor and writer and lives in Cambridge, MA, with his wife and dog.