by Raymond Erickson

Published January 17, 2022

Tempo and Tactus in the German Baroque. Julia Dokter. Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2021. 523 pages.

This is a book that many of us have been waiting for: one that tackles the frustrating problem of tempo and meter in the Baroque era with scrupulous scholarship, a clear-eyed sense of limits, and the perspective of a practicing musician. It is not an easy read, and the author, Julia Dokter, limits her discussion to the German Baroque, and that mainly in the north; moreover, her discussion of actual music is focused primarily (but not exclusively) on north German organ music. However, this also means that her book is very relevant to interpreting the music of Johann Sebastian Bach.

The weighty tome of over 500 pages is divided into three main parts: Treatise Theory, Score Analysis, and Synthesis. Although she refers to virtually every German theoretical writing of the period, she dwells primarily on two of them: Praetorius’s Syntagma musicum III (1619), which establishes the foundations of German metrical theory, and Kirnberger’s Die Kunst des reinen Satzes in der Musik, Part 2 (1776), which presumably reflects the views of that author’s teacher, J.S. Bach. For Praetorius, tempo is based on the concepts of tactus and proportionality inherited from Renaissance notation (“when the measure of one type of meter lasts the same length of time as the measure in the new meter”), whereas Kirnberger, while still maintaining some elements of proportionality, advocates the concept of a tempo giusto (appropriate tempo), calculated from the meter signature, the dominant note-values, and verbal indications (if any).

The weighty tome of over 500 pages is divided into three main parts: Treatise Theory, Score Analysis, and Synthesis. Although she refers to virtually every German theoretical writing of the period, she dwells primarily on two of them: Praetorius’s Syntagma musicum III (1619), which establishes the foundations of German metrical theory, and Kirnberger’s Die Kunst des reinen Satzes in der Musik, Part 2 (1776), which presumably reflects the views of that author’s teacher, J.S. Bach. For Praetorius, tempo is based on the concepts of tactus and proportionality inherited from Renaissance notation (“when the measure of one type of meter lasts the same length of time as the measure in the new meter”), whereas Kirnberger, while still maintaining some elements of proportionality, advocates the concept of a tempo giusto (appropriate tempo), calculated from the meter signature, the dominant note-values, and verbal indications (if any).

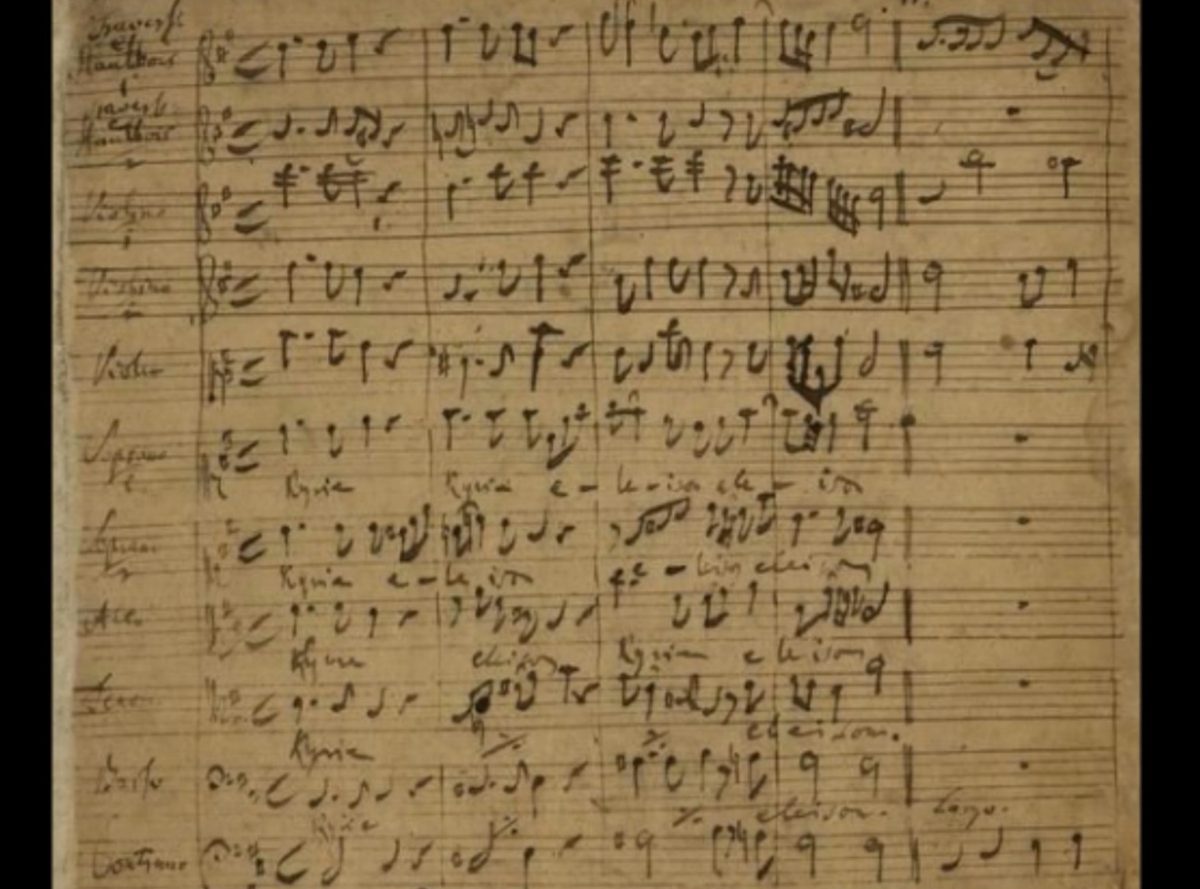

It is impossible here to detail her arguments. But they are supported almost exclusively by historical sources; her analysis of scores is also based primarily on historical prints and manuscripts, rather than modern editions.

To illustrate the practical application of the theoretical findings, Dokter examines works by Weckmann, Buxtehude, and others before turning to J.S. Bach: the Leipzig Chorales, Mass in B Minor, the Musical Offering, and especially the Art of Fugue, arguing that the earlier autograph version of this work shows in its sequence of meter signatures a gradual deceleration of tactus tempo, whereas the revised (published) version does away with this large-scale organization through the reordering and addition of movements. Moreover, she feels that changes of meter Bach made from early to late versions of the Art of Fugue were done to more accurately reflect the desired Affekt, not a change of tempo.

Dokter also proposes an interpretation of the puzzling, old-fashioned meter signature [] of the Gigue of the 6th keyboard Partita. This symbol was a post-Renaissance but, by 1730, archaic sign for the “large alla breve” for measures of two whole-notes, equivalent to 2/1 meter in modern notation; for Dokter it signifies here a weightier Affekt than the symbol for cut-time

[], which is found in the Partita’s early version of 1725, although not necessarily a different tempo. She also suggests — citing Michael Collins (1966) and Natalie Jenne/Meredith Little (2001) — that [] might have alerted performers “to the tradition of resolving duple meter units into triplets,” since there are, unusually, no characteristic triplet figures in this Gigue. (In the Renaissance the circle meant triple division, although of the breve).

Dokter’s very short discussion of dance — which she makes clear is not a central interest of her research — does have a few problems. For example, she fails to distinguish between the solemn French courante and lively Italian corrente: after the early 17th century, only the former can be documented as an actual dance, and their musical styles — and meters — are totally different. She also does not recognize that the ‘Courante” of four of the French Suites are really correntes, a not unique instance of Bach mislabeling compositions.

Throughout the book, Dokter is careful not to claim too much. She emphasizes right at the beginning that she will not propose specific tempos (e.g., metronome values) for any meter or piece of music, believing that tempo is partly the result of particular circumstances; moreover, no German source offers that kind of precise information. Her concern is with relative tempo, which allows a range of reasonable tempi for any given work. This will no doubt frustrate those who want to be told how fast or slow to play something, but it will also frustrate those who think that any tempo at all can be applied to a specific piece. But there is so much information here concerning specific meters and their historical development that anyone who can digest it all will approach the music of the German Baroque with new understanding, conviction, and a sense of freedom.

Raymond Erickson’s “Reassessing Bach’s Violin Ciaccona” has recently been released as Episode 12 on the American Bach Societys “Tiny Bach Concerts” streaming video series: https://americanbachsociety.org/videos/video13-erickson-fang.html