by Steven Silverman

Published February 7, 2022

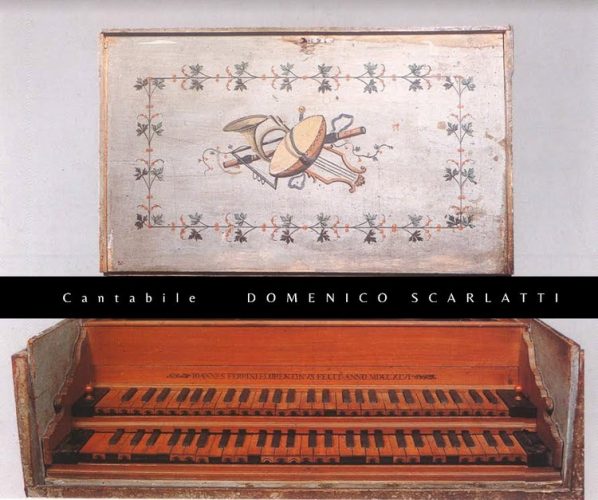

Cantabile: Domenico Scarlatti. Luisa Morales, harpsichord-pianoforte. FIMTE 2021 – 3237816.

The star of Luisa Morales‘ uniformly excellent recording isn’t the performer or the repertoire, it’s the keyboard instrument: a hybrid with a lower manual on which the strings are plucked and an upper manual where the strings are struck by hammers.

Yes, a harpsichord-pianoforte. Described as a “cembalo a penne e martelletti” (harpsichord with quills and hammers), it was made in 1746 by Giovanni Ferrini (a pupil of pianoforte inventor Bartolomeo Cristofori) and is the only such instrument currently known. The instrument somehow reemerged in 1940 in the possession of Corradina Mola, a pioneer of the rebirth of harpsichord playing in Italy, and is now housed in the Museo San Colombano in Bologna. Although presently unique, its workmanship is of such quality and expertise that Ferrini likely made more of them. The instrument has been fully restored, and Morales has used it in concert and for this recording.

The pianoforte sound is exceedingly subtle, a bit like a clavichord, or like a weak buff (lute) stop on a harpsichord. Charmingly, Morales likens it to a cembalo with hammers and feathers. Its lowest register occasionally recalls a ghostly string bass. It is less resonant than even a Stein fortepiano of Mozart’s time, having a dynamic range (to my ear) of piu piano to mezzo piano. The sound is sweet and, once the ear adjusts, there is plenty of expressive nuance, especially in Morales’ hands. The instrument allows her to differentiate, albeit slightly, melody from accompaniment. She also coaxes nice tapered phrase endings from it, and achieves modest crescendos, particularly of repeated chords.

Morales’ 41-minute program contains six Domenico Scarlatti sonatas (K. 132, K. 208, K. 209, K. 213, K. 234, and K. 384), and one by Antonio Soler (R.49 d minor). Her tasteful and effective registration choices include using the pianoforte manual for accompanying harpsichord melodies, for both echo and reverse-echo effects where the soft pianoforte manual precedes the loud harpsichord statement, as contrast in sequences, for variety on repeats, for playing one of two imitative voices, and sometimes — as in the highly expressive g minor sonata K. 234 — for extended solos. Morales is alert to changes of mode, and often makes telling use of the pianoforte manual for changes to minor within predominantly major key sonatas (as in the A Major K. 213 and the C Major K. 132). The manual does seem less nimble than the harpsichord manual — certain faster figures in K. 384 sounded a bit sluggish on the pianoforte but were appropriately sprightly when executed on the harpsichord. Perhaps because of this, the one fast piece presented here, A Major K. 209, makes minimal use of the pianoforte registration.

Luisa Morales clearly knows what she is about with these pieces. An acclaimed performer on both harpsichord and fortepiano and director of the annual International Spanish Keyboard Music Festival in Almeria, Spain, she is to the manner born in this repertoire.

Most of the music on this recording are ceremonial-lyric pieces with stately ostinato chordal accompaniments, overlaid by expressive melodic figures. It’s hard to play legato on either manual due to the absence of a damper pedal, but she executes it nicely and unobtrusively. Examples here include the gorgeous K.213, much of the famous C Major K. 132 and d minor K.208 (a personal favorite).

Morales plays these pieces with plenty of emotion without being cloyingly emotive — rubato is tasteful and preserves the underlying pulse, the more florid figures properly retain their melodic character, trills sound are typically melodically rather than as obtrusive buzzes, although several of the extended trills might have been a little less uniform. Consistent with Ralph Kirkpatrick’s dictum that Scarlatti wrote the notes he wanted played, she avoids ornamentation (even on repeats, all of which she observes). Her well-chosen exception is K.213, where the melodic line invites additions.

She also largely avoids staggering the two hands but still bends melodic lines to avoid rhythmic monotony. Her tempi tend to be slightly on the slow side — Scott Ross’ quicker C Major K. 384, in contrast, is less ceremonial but more dancelike — but are convincing.

A few small caveats. The recording seems closely miked, so there is a lot of audible mechanical clatter, especially noticeable on the pianoforte manual. Also, pitch is A 392, which seems low for Scarlatti but, as Morales says, the instrument is so delicate that keeping the strings under lower tension is a necessary precaution. Finally, the recording is available exclusively online — from Amazon and other streaming services. At present, there’s no plan to release it on CD.

So what might Scarlatti have thought of this instrument? Did he ever play one? His royal patron Maria Barbara’s will and testament lists several pianofortes among her keyboards, but does not list a cembalo a penne e martelletti. And although Ralph Kirkpatrick surmises that Scarlatti wrote a few sonatas for the nascent pianoforte, he cautions that Scarlatti’s writing is so highly idiomatic to the harpsichord as to militate against transfer to either the clavichord or the piano. This recording suggests otherwise — at least for the pianochord/harpsipiano played so well here by Luisa Morales.

Steven Silverman is a pianist and harpsichordist whose performances include concerts at Weill Hall in New York and the Salle Cortot in Paris. He and his wife, the violinist and violist Nina Falk, are co-founders of the Arcovoce Chamber Ensemble, now in its 23nd season, and for many years a resident chamber ensemble at Washington D.C.’s Phillips Collection.