by Mike Huebner

Published March 28, 2022

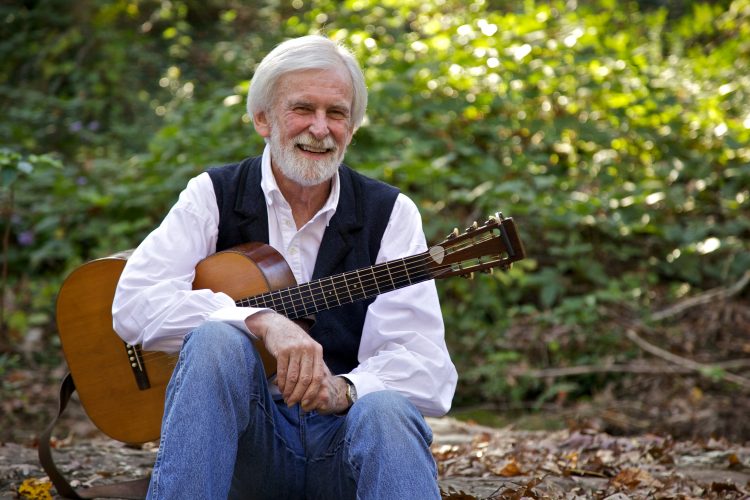

In a second-floor studio in an Alabama suburb, Bobby Horton can be found probing deep into America’s musical past. From tunes of the Civil War to songs by early blues and jazz musicians, the 71-year-old folk musician has been on a historically informed journey ever since his grandfather introduced him to the banjo. Horton has worked closely with the popular documentary filmmaker Ken Burns, whose The Civil War, Baseball, and 14 other PBS programs bear Horton’s mark as a performer, collector, composer, and adviser. His contributions to more than 20 National Park Service films reflect his intense interest in conservation and centuries past, and his approach—unique by necessity—to recreate what long-ago listeners might have encountered.

Horton is on the soundtrack for Ken Burns’ latest project, Benjamin Franklin, which airs on PBS starting April 4th.

At his home studio in Birmingham, scattered among stacks of books and sheet music and shelves lined with recording equipment, computers, tapes, CDs, and microphones, are historic instruments, some dating from the 18th and 19th centuries. A 300-year-old German fiddle, a Dobson five-string banjo, and battle-scarred brass including a cornet, trumpet and valve trombone, are a few of the artifacts that help guide his exploration. Horton seems an artistic embodiment of William Faulkner’s beloved Southern maxim: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

“My grandpa played old-time banjo,” Horton recollects as he fingerpicks the five-stringed instrument. “He learned from his father, who was born in the 1870s, and his father learned banjo from his daddy, who was a Confederate soldier. He told me my great-great-grandpa played this in the Civil War and, at the time, I thought, ‘this was the way it sounded.’”

Horton has explored instruments since he was a child growing up in Birmingham. For the past five decades, he has been a multi-instrumentalist with Three on a String, a mélange act that routinely performs country, classical, bluegrass, and folk music with symphony orchestras and country music stars.

“I majored in economics and accounting,” he says. “I’m not an academic scholar of early music and don’t claim to be. I stumble across things—new scores, instruments. I try to get across to an audience how things might have sounded.”

Horton points out that during the Civil War, 3,000 songs were written in four years in the North, in addition to about 1,000 Southern tunes, all published as sheet music. Many have found their way into Horton’s collections and then into his live stage presentations. He began recording one-man versions of Civil War music in the 1980s, inspired by his grandfather’s collection of 78 rpm records of early string bands. Horton’s broad output includes ten CDs of Confederate and Union army songs—“I have relatives on both sides of this war,” he says—striving for some measure of cultural fidelity from an era when every performer, every home-sick soldier carrying a bugle or a fiddle in his pack, would make a tune his own. The notion of strict “authenticity” was unimaginable.

Yet to his way of thinking, in the Deep South, styles evolved slowly if at all. “With no radio, this is the way people played” for decades, he offers. “I studied my grandpa’s records and the way the instruments were played during the Civil War. I believe this music was largely unchanged by the time these recordings were made.” The combination of studying the old family recordings while recreating these songs on historically accurate instruments gave him a performing-scholar’s insight into how the music might have sounded.

Horton’s father, a World War II veteran who was stationed in North Africa, told stories that further sparked his interest.

“They found a short-wave radio in the desert of Tunisia and it picked up the BBC,” he recalls his father telling him. “The first song they heard was Glenn Miller’s In the Mood.” They were facing the grim, dispiriting reality of war, but suddenly everybody changed their attitude. “The importance of music is right there. Growing up, I could sing every single Glenn Miller arrangement from start to finish. To me, that was old guy music! But I was fascinated with World War II because every adult male in my life was a World War II vet. And they all would mention the music.”

Along the way, Horton’s focus expanded to include music of the 1930s, then a fascination with the late 1920s. Tin Pan Alley and early jazz connected even further back, back to the Civil War. “It started with the Civil War Centennial when I was 10 years old. I found accounts of soldiers talking about a band playing The Bonnie Blue Flag and how they made a stand right there. So music is more than just tunes on the radio. It’s how you get to know the people.”

Battle Hymn of the Republic, he explains, originated with a song called Say Brothers, Will You Meet Us? by South Carolinian William Steffie. Julia Ward Howe took Say Brothers and changed some of the words. Dixie, which was one of President Lincoln’s favorite tunes, was written by Daniel Emmett, from Ohio.

“The irony is that a Southern guy wrote the Yankee anthem, and a Yankee wrote the Rebel anthem.”

Horton’s interest in Sacred Harp is an example of his hands-on approach, having taken turns leading hymns in a rural church in the hills of northern Alabama.

Although the Sacred Harp a cappella tradition originated in New England, it became especially prominent in the South, with an annual national convention held in Birmingham. Horton owns an original copy of the 1835 edition of Southern Harmony, a volume of 335 hymns in shape-note notation. The hymns are performed in a hollow square, with singers facing inward toward a singing leader.

“I got in the square down front, with all these people singing at me. I got goose bumps. I’m thinking, Man, I’m hearing it. This is what it sounded like. That’s what I go for. I try to get as close to that experience as I can.”

Horton’s anecdotes reveal a unique methodology, a combination of historical researcher and time-traveling ethnomusicologist. More important than any such labeling are his acute observational skills, whether traveling in the Appalachians, plucking a banjo along with an old 78, or diving into his home town’s history.

“I found some tunes that were recorded in Birmingham in 1927 that form the basis for some of my stuff. Daddy Stovepipe was one of the guys on the recording.” Alabama-born Daddy Stovepipe and his wife, Mississippi Sarah, (real names: Johnny and Sarah Watson) were multi-instrumentalists, singers, and songwriters, and are credited as among the first Black blues performers to make recordings. They performed in a style that is practically lost to modern ears. “I Heard the Voice of a Pork Chop” is one such ballad, with recondite story telling, clearly operating on several cultural levels at once.

I Heard the Voice of a Pork Chop (partial lyrics):

I ain’t had no use for chicken since way back yonder last spring

For a chicken tried to peck me ‘cause I stepped on his way

Old chicken caused me to go to jail. I don’t let no chicken do that

I would have stole every hen he had but I found that he was fat.

Well I was walking down the street today just as hungry as I could be

And I walked right into a swell cafe and this is what they said to me:

“Hey won’t you have some chicken with me?” “Oh no, I’ll have some beef.”

Anytime a man would chew chicken he had to pay for all of his teeth.

I heard the voice of a pork chop say, “Come up to me and rest”

You talk about liver, stew and beans, but I know what’s the best

There’s pork chop, beef chop, ham and eggs, turkey stuffed and dressed.

I heard the voice of a pork chop say, “Come on to me and rest.”

“I used the instruments that those guys recorded with,” says Horton of his own performances. “Imagine a Black man in downtown Birmingham in 1927, with all the oppression that’s going on around him. But there’s joy in that community, still. I thought about my Dad in World War II. If you want find out about history, you find their music.”

Michael Huebner is a freelance writer based in Birmingham, Ala. He is a former classical music critic and fine arts reporter for the Birmingham News and AL.com. He also has written for the Kansas City Star, Austin American-Statesman and Classical Voice North America.