by Carol Lieberman

Published April 25, 2022

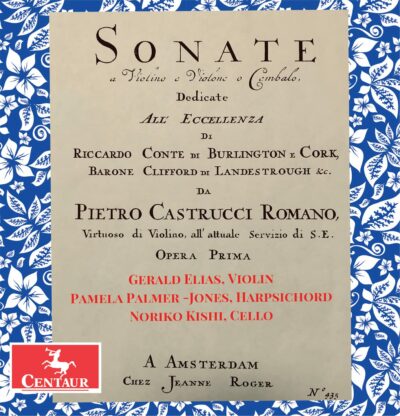

Pietro Castrucci Sonate a Violino e Violone. Violinist Gerald Elias, cellist Noriko Kishi, harpsichordist Pamela Palmer-Jones. Two CDs. Centaur Records, CRC 3932/3933

Violinist Gerald Elias has just released an excellent two-CD set of the Sonate a Violino e Violone o Cembalo Opera Prima by Pietro Castrucci Romano (1679-1752). Billed as the first complete recording of Castrucci’s 12 Sonatas, Op. 1, they comprise a fascinating and welcome addition to the Baroque violin repertoire.

Castrucci is not very well known among violinists—but should be. Born in Rome, he studied violin with Arcangelo Corelli and moved to London in 1715 at the invitation of Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, at whose home he stayed for six years. Castrucci’s virtuosity led to his appointment as leader of the newly founded Royal Academy of Music, the opera company led by Handel, a position he held until 1737. In addition, Castrucci collaborated with another of Corelli’s students living in London, Francesco Geminiani, often performing with his countryman and Handel. Although Castrucci’s compositional output is relatively small, his incredible skill and creativity are much to be admired.

The sonatas themselves, from 1718, are striking in their originality. Rather than the standard sequences that often dominate the music of Corelli and Vivaldi, many of Castrucci’s sonatas are more inventive harmonically, and greatly expand the emotional possibilities of tonalities, modulations, and instrumental combinations. This is especially true in Sonata IV, which features an interesting dialogue between the violin and cello in running sixteenth notes in the Andante, a delightful Allegro e Battute with dotted rhythms, and a lovely Adagio to which Elias introduces some expressive ornamentation.

The sonatas themselves, from 1718, are striking in their originality. Rather than the standard sequences that often dominate the music of Corelli and Vivaldi, many of Castrucci’s sonatas are more inventive harmonically, and greatly expand the emotional possibilities of tonalities, modulations, and instrumental combinations. This is especially true in Sonata IV, which features an interesting dialogue between the violin and cello in running sixteenth notes in the Andante, a delightful Allegro e Battute with dotted rhythms, and a lovely Adagio to which Elias introduces some expressive ornamentation.

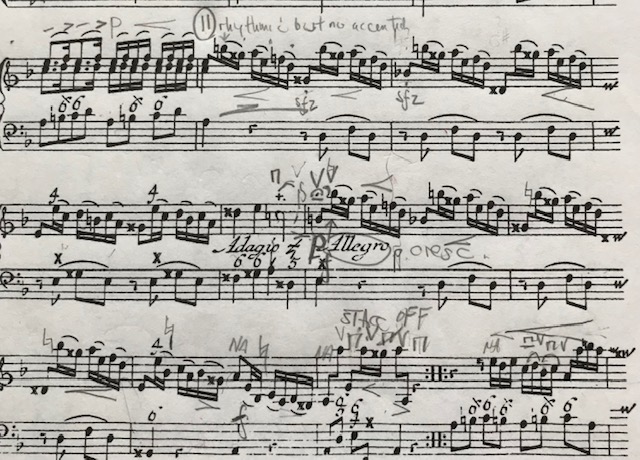

Sonata V has a characteristic movement entitled “Venitiana,” and Sonata VI contains some impressive florid passage work. In Sonata VII in D minor, which seems to be the Castrucci sonata most frequently recorded previously, the composer employs some rather interesting harmonic language, but this could have been better emphasized by the performer, especially in the first movement Adagio, by taking full advantage of the unique characteristics of the Baroque bow. Sonata XII is perhaps the most inventive of the set because of the use of scordatura tuning, which produces different overtones that create a unique sonority. In fact, the entire sonata comes across to the listener as an essay in violin technique and serves as a fitting finale to this Opus 1, his Opera Prima.

A former member of the Boston and Utah symphony orchestras, Elias is a virtuoso violinist with a brilliant technique and perfect intonation. In addition to his impeccable performance, he often adds his own tasteful and stylistic ornaments. Elias collaborates here with cellist Noriko Kishi and harpsichordist Pamela Palmer-Jones. He uses a violin “adapted for Baroque playing,” built by his son, Jacob Elias, with gut strings tuned to A=415, and a French-style Baroque bow. Kishi performs on a cello made by the modern maker Biagio Marsigliese (1885-1957) and a modern-style bow made by Dominique Peccatte (1810-1874). Palmer-Jones performs on a French Double harpsichord built by Morgan and Dunstan, modeled after a 1707 design by Nicolas Dumont.

Despite the compelling performances of Elias and his colleagues, I do have a few quibbles. As mentioned, Elias does not fully exploit the characteristics of his Baroque bow, whose strongest part of the sound occurs in the middle of the stick as opposed to its modern counterpart, with the strongest articulation at the frog. Because of this, the Baroque bow naturally enhances dissonances and other interpretive aspects of the musical line. Another concern is the execution of trills, which in the Baroque style are customarily started slowly and gradually increased in speed in order to emphasize the expressivity; Elias almost always plays his trills fast. There was also a bit too much of a difference between the very strong sound produced by the cellist Noriko Kishi’s modern-style bow articulation that contrasts with the softer sonority of Elias’s Baroque bow.

That said, Gerald Elias is a first-class violinist, with an impeccable modern technique that enables him to perform these sonatas with aplomb and fine musicianship. Bravo to him for producing this superb recording of these 12 sonatas, and introducing the listener to this original and little-known violin music.

Carol Lieberman’s career as performer and teacher on both Baroque and “modern” violin spans a period of more than fifty years. She can be heard on her recent two-volume set of CDs, The Art of Carol Lieberman, Centaur Records CRC 3701 and 3702.