by Sophie Genevieve Lowe

Published May 30, 2022

Introducing Early Music: the Americas, an online series from EMA.

To Benjamin Franklin—Marseille, France

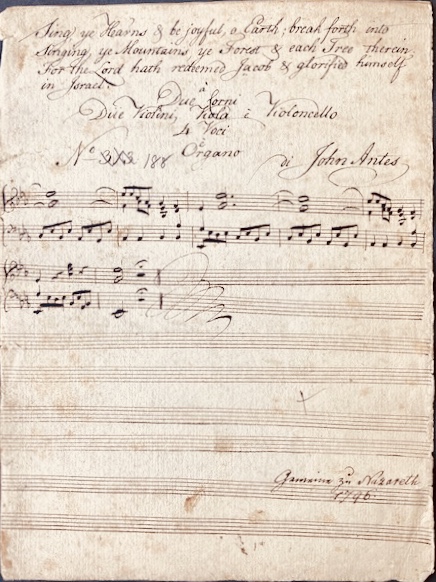

“Sir, You may perhaps still remember a young Man wich in the Year 1763 amused himself with making Musicall Instruments such as Harpsicords Violins etc. whome Curiosity and Desire of Learning once led to your House at Philadelphia, without anything to introduce him but a little American Cordiality. This Man am I… And this is the only Motive wich induce me to send you with the Pressent a Copy of six Quartetetto’s wich I have lately compossed…” – John Antes, Cairo, Egypt. July 10, 1779.

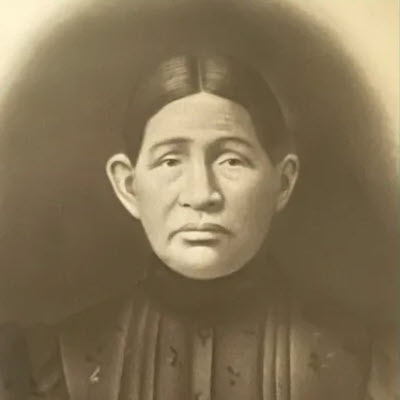

When we consider the vastness of what’s called “early music,” how often do we find ourselves contemplating historical musicians of the Americas such as John Antes (1740–1811)? Does his name conjure visions of music-making in the Pennsylvanian Moravian community or violent run-ins with Egypt’s Mameluk regime? Can we hear his string trios, some of which were sent as far as France and India? John Antes stands in a long line of under-explored musicians born in the Americas between European colonization of the New World and the 19th century.

To shed light on the fascinating characters who populated the early Americas’ broad musical landscapes, EMA’s Emerging Professional Leadership Council (EPLC) is proud to announce the launch of our new digital-essay series, Early Music: the Americas. Beginning in June and ending in August, each essay of Early Music: the Americas will introduce an individual musician and share stories of their life and the music they played.

Collectively, these essays will explore a frontier in our knowledge as researchers and our historical imagination as performers. On this extensive journey through genre, culture, and geography, it is our hope that Early Music: the Americas will illuminate points of connectivity between the land we live on and the musical practices we are dedicated to realizing. We also hope that these essays will help to inspire EMA’s members to pursue their own canon-defying exploration of music from the Americas.

While Spanish, French, and British colonizers competed for military, economic, and cultural dominance of the New World, multitudes of Indigenous peoples and communities of enslaved Africans struggled to retain political and cultural independence. Although the musical traditions practiced by these peoples is not the focus of this series, it is undeniable that their tenacity, resistance, and eventual forced assimilation into European communities has left a lasting impression on the West’s musical heritage.

While Early Music: the Americas will focus geographically on the Western Hemisphere, the subjects of these writings will necessarily reflect aspects of interconnected and competing cultures of the wide Atlantic World. For instance, the aforementioned John Antes was born in Pennsylvania where he began his musical training. He would go on to pursue work as a Moravian minister, first traveling to the German-speaking lands of Europe as a student, and eventually landing in Cairo, Egypt as a missionary. Where, you ask, were his compositions published? London, of course.

On the flipside of this experience are musicians like Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla (c. 1590–1664). Born in Malaga, Spain, Gutiérrez de Padilla settled in Puebla, Mexico (then New Spain) in the early 1620s. Initially working under the supervision of fellow Spanish-born music master Gaspar Fernandez, Gutiérrez de Padilla would distinguish himself as a prolific composer and master of his craft. He was even a luthier, and his shop is known to have sent its instruments as far as Guatemala.

In the middle of these experiences were those born into colonial societies or newly independent nations and who found themselves, in one way or another, responsible for either maintaining European cultural identities or borrowing from those identities in the pursuit of something different.

In the former category we have Francisco López Capillas (1615–1673), the first Novohispanic maestro de capilla of the Mexico City Cathedral, whose musical work was critical in maintaining Catholic hegemony in one of New Spain’s most populous regions.

In the latter group there is Timothy Olmsted (1759–1848), a New Englander whose formative musical experiences took place as a bandsman in the Continental Army during the American War for Independence. In many ways, the only difference between Olmsted and his British counterparts was the uniform he wore. Yet Olmsted and his contemporaries would exploit their similarities to lay one facet of the cultural foundations of the United States’ musical identity.

While we may have first fallen in love with early music through the works of Bach or Corelli, we are excited to share our passion for the rich and, at times, complex and painful stories of American music makers. We invite you to join Early Music: the Americas by looking for these essays in EMA’s weekly E-Notes starting in June, and by keeping up with this project on EMA’s Facebook and Instagram pages.

Articles in this series: