If you’ve ever sung or played a madrigal from an edition on IMSLP, you’ve probably engaged with the work of Allen Garvin, whose International Music Score Library Project corpus surpassed two thousand uploads last year.

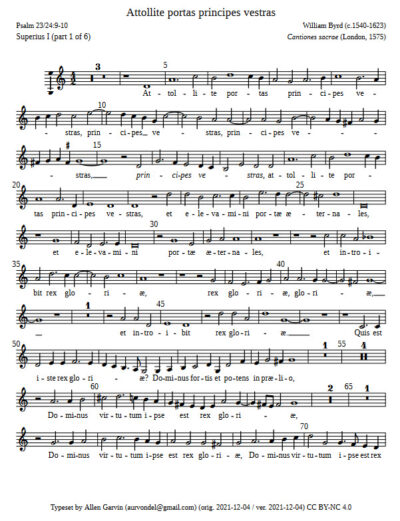

A computer programmer and mobility systems engineer by profession, Garvin is undaunted by the technical aspect of typesetting editions. He uses software called LilyPond, which turns specially formatted text input (which computer programmers are likely to be comfortable with) into musical notation. This process enables Garvin to typeset editions with incredible speed. Although Garvin began to dabble in typesetting as a college student in the 1990s, his project of typesetting whole editions, particularly editions of 16th-century vocal music, gained momentum when he took up the viol nearly two decades ago.

After playing the recorder for several years, Garvin came to the viol when the local Dallas-Fort Worth area viol community needed someone to replace a treble viol player who had moved away. “Susan Scheib, who is our local cat-herder, got me to play viols. It is my instrument for life now,” says Garvin with a smile.

Garvin began creating typeset editions of 16th century vocal music to play with his newfound viol consort. They still play together every week. “Sixteenth-century vocal music is what really calls me,” Garvin explains, and he credits a Hilliard Ensemble recording of Josquin, heard as a college student, as his introduction to early music: “I fell in love with it.”

He began uploading the editions he created for his consort online about a decade ago, for the enjoyment of others. Now these editions, with hyper-local roots, are played and sung world-wide.

Garvin partially attributes the expansion of his project to the global expansion of library digitization. “In college in the ’90s, the only facsimiles we had were things on microfilm, and that didn’t provide many opportunities,” he says. “Possibilities have really opened up since libraries around the world have started uploading scans of their holdings. It’s just provided a wonderful resource for me.” Garvin points to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the Bavarian State Library, the Biblioteca della musica di Bologna, and the Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music as particularly key resources.

Even as the number of facsimiles available to Garvin increases, his selection process remains guided by interest and curiosity alone. “I typeset what I enjoy listening to, or I investigate what’s available and choose what looks interesting,” he explains.

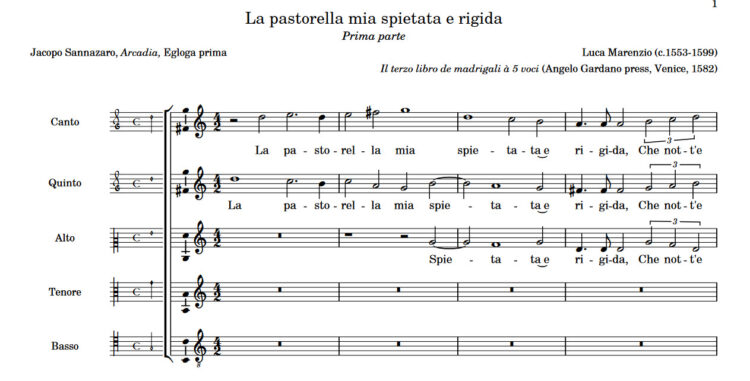

“The music I really love is the madrigal repertoire from about 1550-1590. I return to those over and over again.” This means that Garvin spends a lot of time with facsimiles by Girolamo Scotto or Antonio Gardano, whose Venetian printing houses dominated the 16th-century Italian music publishing industry. Garvin particularly enjoys working from Scotto and Gardano facsimiles, describing them as “easy to read, elegant, and relatively error-free.”

As far as Garvin’s own style is concerned, he takes a very “light touch” approach to editing, striving to create editions that maximize the players’ musical decision-making power. “I try to emulate editions that I like to play from,” he explains, naming editions by the Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae and A-R Editions as among his sources of inspiration.

While Garvin is happy to know that his editions are regularly used by vocal ensembles, he is partially motivated by a desire to make vocal music available to instrumentalists who like to play from parts.

Ironically, Garvin himself is one such instrumentalist. “I love playing from facsimile. The shape of the music is not always available when you look at a piece with bar lines and proportional spacing. It becomes more apparent. It’s also more challenging because you really have to listen to everyone around you. That especially is very rewarding, to carefully listen,” he explains.

It may seem surprising that someone who prefers to play from facsimile would dedicate so many hours to creating modern editions, but Garvin’s project isn’t about him, it’s about the music he loves. He acknowledges that “playing from facsimile is not for everyone. I’d like everyone to enjoy access to this [music]”—regardless of their part-reading preference.

Garvin isn’t paid for any of his editions. In the truest sense of the word “amateur,” with its roots in the word “amor,” Allen’s work is an excellent example of the invaluable contributions to the early-music community of countless unsung labors of love.