The American violin scene is set for renewal as a versatile younger generation replaces their distinguished teachers

In 1966, American countercultural icon Timothy Leary famously advised us to “Turn on, tune in, and drop out.” By then, Stanley Ritchie was associate concertmaster at the Metropolitan Opera, and Marilyn McDonald was working on her doctorate at the University of Michigan — both operating within the realm of the modern violin. Within a few years, however, they would both become pioneers in a very different kind of counterculture, and with a very different credo: take off (your chinrest), tune down (your strings), and drop into the burgeoning world of historically informed performance.

Almost a half-century later, after illustrious careers as teachers and performers, Ritchie and McDonald have both officially retired, marking a change in the guard for the world of Baroque violin. At Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music, Ingrid Matthews took over for Ritchie as of Fall 2021. At Oberlin, Edwin Huizinga succeeded Marilyn McDonald in January this year.

The phrase “end of an era” seems a little out of place in a field whose musical territory spans a thousand years. But it is impossible to overstate the impact Ritchie and McDonald have made on generations of string players. They leave a vast trail of students, performances, recordings, and writings that have permanently changed the face of early music. It would be fair for former colleagues and students — me included, as Stanley was briefly my Baroque fiddle teacher — to wonder how their programs will be the same without them.

They won’t be, and that’s ok. The violin world is in good hands.

Toil, toil, trial and error

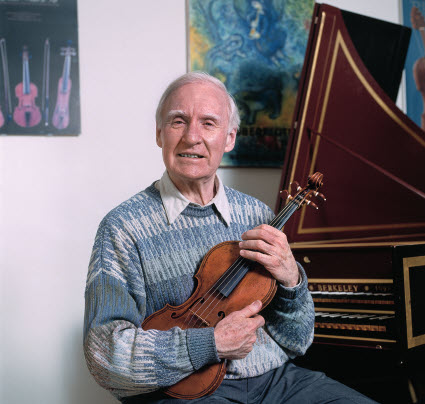

Growing up on a farm in rural Australia, Stanley Ritchie’s first music teachers were nuns at a nearby convent who possessed little knowledge about the violin, but who could read music and play piano. He eventually made his way to the Sydney Conservatorium, then to Paris, and finally to the United States, where he ended up in a graduate program at Yale. He soon ended his studies, finding them unproductive with one notable exception: “I did sign up for one course — performance practice. I didn’t even know what it meant.”

Ritchie had always been interested in the question of musical style and reveled in first encounters with composers like Biber. “When I finally escaped from the Met,” Ritchie explained, “I was playing in a chamber group — New York Chamber Soloists. One of the members was harpsichordist Albert Fuller.” One day, Ritchie suggested that they get together and read some Corelli. “Albert just about jumped in the air.”

Fuller wasted little time in evangelizing: “You know what they are doing in Europe? They are tuning down their violins, putting on gut strings, and playing with old bows.” Ritchie wondered, “Why would anyone do that?”

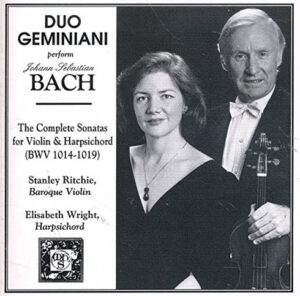

In the early 1970s, Ritchie formed Duo Geminiani with keyboardist Elisabeth Wright and, after years of successful performances and recordings, the pair was invited to join the faculty at Indiana University. (Wright, whose legacy as a performer and pedagogue is no less groundbreaking, retired from IU alongside Ritchie and was replaced by Jonathan Oddie — also a former student and IU alum.)

In the early 1970s, Ritchie formed Duo Geminiani with keyboardist Elisabeth Wright and, after years of successful performances and recordings, the pair was invited to join the faculty at Indiana University. (Wright, whose legacy as a performer and pedagogue is no less groundbreaking, retired from IU alongside Ritchie and was replaced by Jonathan Oddie — also a former student and IU alum.)

“I started out here as some kind of weirdo,” Ritchie recalls. “People thought, ‘He can’t play the violin very well, so he plays Baroque violin.’ Gradually, they began to understand. By the time I retired, no teacher would prevent their students from studying with me.”

‘People thought, He can’t play the violin very well, so he plays Baroque violin. Gradually, they began to understand.’

Like Ritchie, McDonald had been established in the modern violin world before her foray into historical performance, and she is the only pedagogue of her generation to perform and teach both for the entirety of her career. She first came to the Baroque violin by way of a brief encounter with the tenor viola da gamba. At Oberlin, where McDonald started teaching in 1976, gambist and cellist Catharina Meints Caldwell and oboist James Caldwell had purchased a set of viols to play consort music. Avid instrument collectors, the pair also lent McDonald a Baroque violin — all she had to do was to figure out how to play it.

“There will never be another moment like I had,” McDonald remembers. “We had a gift in that we had to figure everything out on our own. We had so many fights in the Smithsonian Chamber Players about the length of a quarter note! I’m an enthusiastic listener of all sorts of music, but nothing could top that in terms of the high it gave you.”

But there were also the lows. Luthiers were rarely well-versed in historical setups, bows were not particularly sophisticated, and strings were unreliable. In her first performance on Baroque violin, and therefore without a chinrest, McDonald recalls having to sit down for fear of dropping her instrument. In another concert, a string broke seconds before taking the stage, bringing her to tears. Ritchie tells a similar story, a performance where he was forced to abandon a repeat due to a rapidly sinking E string.

Students today might feel jealous when they imagine the seemingly endless swaths of long-forgotten music available in the early days of the historical performance movement. But there is more to the designation of “pioneer” or “trailblazer” than being the first to procure a dusty manuscript and stick it onto vinyl.

For all the excitement, their work was just as likely to be painstaking, tedious, or even downright annoying. Learning technique solely from written sources — no matter how descriptive — is hardly a straightforward task, and few reference recordings were available. If musicians today dislike the 15-second wait on an IMSLP download, imagine spending countless hours hand-copying manuscripts from the Biblothèque Nationale de France and shlepping them across the Atlantic, only to find that a smudge or slip of the pen has rendered a rhythm or pitch illegible. While trial-and-error is universal for all musicians, those of McDonald’s and Ritchie’s generation had more than their share of error.

‘Seed pouch for creativity’

It was once commonplace, maybe the norm, for a teacher to be replaced by a talented former student. And while there is much to be gained by continuing a pedagogical line, without a fresh perspective, it can easily result in a cycle of diminishing returns — a theme and variations in which each new variation is less inventive, less original, than the next.

But it takes only seconds of hearing Matthews or Huizinga perform to know that they are far from carbon copies of their teachers — or anyone else, for that matter. They are their own musicians whose reputations have been built on bold, forward-looking, and unique performances. Both embody the wonderful paradox at the heart of early music — the vibrant dynamism that miraculously gels with an obsession for really old music.

As a student, McDonald remembers Huizinga as a “Free spirit, in true Oberlin fashion. Edwin was a lot of fun, quite noisy! He has a trait that we should all appreciate, in that he is the most enthusiastic person about life in general. His enthusiasm is portrayed through his music.” And much more: He’s “well-equipped in all ways and well-schooled in all styles.”

All styles? Hyperbole, of course, but a glance at Huizinga’s discography and performance schedule makes the assertion not so far-fetched. In addition to playing with celebrated period groups like Tafelmusik and ACRONYM, an ensemble he founded with violinists he met in McDonald’s studio, Huizinga delves frequently into contemporary music, bluegrass, Celtic, rock, and jazz — often all in the same concert. He has toured extensively as part of the folk and Baroque duo Fire & Grace, alongside guitar player William Coulter, and he is also a member of indie rock group The Wooden Sky. He’s a noted composer, too, with commissions from organizations such as Opera Atelier and Canada’s National Arts Center Orchestra.

Weeks after beginning his professorship at Oberlin, Huizinga still seems incredulous, even giddy, about his new role. At the same time, he recognizes the enormity of the responsibility: “I have huge shoes to fill, I know that. Marilyn opened up the world of the Baroque violin for me. She taught me about exploring the sound world of Baroque music and also modern music. She was often playing contemporary pieces on the Baroque violin.

“She gave me the foundation to feel secure about the technique, and just being a huge advocate of the sound qualities that I could experiment with and just live in.”

While Huizinga says that “The Orange Blossom Special” was a far cry from anything in McDonald’s list of assigned repertoire, “even the folk collaborations came out of my experiences with Baroque music, because that’s how I started improvising, how I started ornamenting.”

‘If someone really is interested in folk music and wants to learn about the fiddle, I can show them composers who share boundaries with Baroque composers.’

As a teacher, Huizinga is interested in cultivating a variety of artistic avenues for his students. “I like to think of early music as a seed pouch for creativity. I am already asking students where their interests lie and seeing where I can support them. If someone really is interested in folk music and wants to learn about the fiddle, I can show them composers who share boundaries with Baroque composers.”

“The most important thing that I can do as a teacher,” Huizinga continues, “is to use the Baroque violin as a catalyst for them to find out who they really are in music.”

‘No wrong notes, only improvisation’

Upon learning of Matthews’ appointment to IU’s Historical Performance Institute, Ritchie says he was delighted. “She has always been an extremely warm, musical player. We have disagreements, but that’s how it is. You have to find your own way. Whatever I did at IU, I did not make clones.”

As for Matthews, it might be said that her trajectory toward the Baroque violin began well before she met Ritchie, although she may not have known it yet. As a child, she insisted on playing without a chinrest, finding it both awkward and uncomfortable. “Eventually,” she recalls, “I made peace with it. I forgot about that feeling until I first held the Baroque violin in Stanley’s office. I suddenly remembered how it was supposed to feel.”

At the time, around 1986, Matthews was primarily studying modern violin with the famed teacher Josef Gingold but was struck by Ritchie’s “really cerebral approach.” She had grown accustomed to an almost athletic treatment of the violin, but “with Stanley, the goal isn’t the violin playing. The goal is its application to different music.”

“We had whole lessons devoted to small amounts of music, spending an hour on just a few lines.” (At this, we both had to laugh — it’s one aspect of Ritchie’s teaching that has not changed in the 30 or so years separating our studies with him.) “I assume he taught me everything I know.”

That’s generous praise, but Matthews has forged her own path in the performance world. A full list of her exploits would take a lot of ink, but suffice it to say that she has performed with, directed, or been a soloist with just about every major period ensemble in North America and plenty more overseas. In 1994, she founded the Seattle Baroque Orchestra with keyboardist Byron Shenkman, serving as its artistic director until 2013. She continues to perform actively with revered ensembles like Musica Pacifica. Her recordings of Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas are, in my completely biased opinion, paralleled only by Stanley Ritchie’s.

Matthews is additionally a jazz and swing violinist as well as a talented visual artist. One of her paintings rests on Ritchie’s living room wall, where it can be admired while sipping on one of his world-class “Stan-hattans.”

As a teacher, Matthews spends a lot of time thinking about rhythm, arguing that melody instruments are susceptible to certain lapses in that department. She spends time focusing on the art of improvisation, a very personal area of exploration.

When teaching, “I try to balance detail-oriented work with the flow of the music,” she says. “There are no wrong notes, only improvisation.”

‘Historically curious performance’

What’s next in early music? Huizinga’s memorable reply: “Whoa! Dude!”

He continues, “There is so much music left to be cataloged and brought to life,” he continues. “None of this music is ever going to die — if it has survived 400 years, it’s going to survive some more. The beautiful thing about the cycle of life is that everyone gets to discover this music for themselves.”

Huizinga also spoke of the possibilities of bringing concepts from performance practice to newer repertories — Brahms and beyond. He hopes that every student at Oberlin, no matter their area of focus, might graduate with at least some exposure to historically informed performance or, as he calls it, “historically curious performance.”

Echoing his point, Ritchie argues, “First of all, ‘early music’ is a silly term. As far as I am concerned, historical performance takes us right up until yesterday, playing any music in the style with which the composer would be familiar. It’s about the ability to learn and not to impose yourself on a piece, keep your options open, keep your mind open to suggestions from the music. That way you become your own musician.”

‘A focus on being inclusive, not exclusive. That’s tricky in a field largely about dead white men.’

So, are designations like “early music” and “historical performance” losing their meaning? Not quite, but they may need re-defining. While historical performance is unlikely to be the musical mainstream any time soon, it has nonetheless gained tremendous cultural and artistic capital since its early years. Just look at music schools like IU and Oberlin, where a large proportion of Baroque violin studios are composed of modern performers curious about the world of HP. Such a dynamic might even extend to performance spaces — McDonald says she would “love to see a concert at Oberlin of half contemporary and half early music.”

But early music also has much to accomplish in advocating for itself within the world at large. Matthews observes, “We never know what artists of the future are going to bring forth. And we need to continually convince the wider world that this is something worth doing. That, and focus on being inclusive, not exclusive. That’s tricky in a field largely about dead white men.”

On that frontier, we have a long way to go, but the conversations have already started. Old music brings old problems, but historical performance is still a young field. And as Leary wrote, “You’re only as young as the last time you changed your mind.”

Jacob Jahiel is a writer, editor, and viola da gambist currently living in Montréal. He was a 2022 Rubin Institute for Music Criticism Fellow and is a recent graduate of the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University, where he received an M.A. in musicology with an outside field in historical performance.