The French-American Lutenist is riding a wave to early-music stardom — on both sides of the Atlantic

In 2012, the still-newish Ensemble Pygmalion released a recording of Bach’s B-minor Mass in its shortened, 1733 Missa brevis version. It’s wonderful, full of sparkling choral sound. But after the first chorus, as the singers take their seats, the continuo team emerges. Their texture is thick with counterpoint, largely thanks to an active and prominent theorbo.

There’s no mistaking the signature stamp: Thomas Dunford was here.

His singular sound is easy to recognize. The lutenist’s continuo realizations are compositions as much as accompaniments, imaginative countermelody sculpting the harmonic shapes. Occasionally, those melodies threaten to grate against the foreground tunes, but Dunford has an expert way of holding dissonance until its absolute breaking point, making his sly resolutions all the sweeter. His chords surge and ebb organically, guiding the energetic flow around him. And when he flourishes with guitar-ish strums, he often does so against the reigning meter, providing a zip of unexpected rhythmic contrast.

Dunford spurns the notion that continuo should have parameters. After all, rules are meant to be broken — or, his word, “explored.”

“There’s no right way to do things, but you realize that this gesture can help people better,” he said. “How can I help the sounds that are happening around me?”

Even with six time zones between us — I’m on Zoom from New York, he’s in Paris — his casual yet contagious intensity made it easy to see why collaborators say they love working with him.

It’s that inviting presence—coupled with an explorer’s spirit — which has launched Dunford’s meteoric rise toward the top of the global early-music scene. In the decade since BBC Music Magazine dubbed him “an Eric Clapton of the lute” in 2013, Dunford has remained a central fixture of the European Baroque scene’s A-list ensembles. His Ensemble Jupiter has become the rock stars of historical performance, regularly selling out concert halls around Europe and North America. And he’s leading the ensemble on forays into experimental territory, championing this countercultural idea that “Baroque” ensembles can extend beyond the 18th century.

And yet Dunford says his career just…happened. “The way that I love playing the lute, it just ended up being my life,” he said. “I just rode the wave.”

Dunford’s parents, the viola da gamba players Jonathan Dunford and Sylvia Abramowicz, say that was the ethos of their household: following fervent passion, just as they had done when choosing their own career paths. Jonathan, a native New Yorker, brought to the household the folk, rock, and jazz that would later influence his son’s style so heavily — the most prominent influence from the American side of his upbringing, said the lutenist. From his French mother’s side: la gastronomie, la philosophie, and, of course, la musique classique.

As an early ’90s child in Paris, the young Thomas gravitated toward plucked instruments — ukulele first, then guitar — but resisted his parents’ nudges toward music lessons, as do many children. Music, he recalled, “was the dorky thing my parents did.” But one morning, at the biennial early-music workshop that his parents teach in the hills of Provence, nine-year-old Thomas picked up the treble lute for the first time. It was only supposed to be an antidote to his boredom, but he showed uncanny talent. That very afternoon, the parents told me, Thomas performed the top part in the workshop’s lute consort performance.

One day, Jonathan came home to his son sitting at the piano — an instrument Thomas ostensibly did not play — plunking all four voices of Bach’s Trauerode from memory. The father had played the piece a year earlier, and it was still note-perfect in the boy’s head.

Dunford thought he’d follow his idol, lutenist Paul O’Dette, to an undergraduate degree at the Eastman School of Music, but his parents convinced him to stay closer to home. He enrolled at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis to study with Hopkinson Smith, the American expat who taught there until 2020. Dunford viewed Smith as something of a guru, a rigorous teacher who demanded high standards with kindness and benevolence. Smith gave a cardinal lesson that enables Dunford’s unrestrained approach: If you want to justify something, you’ll always find it in a treatise.

A cardinal lesson that enables Dunford’s unrestrained approach: If you want to justify something, you’ll always find it in a treatise.

While in Basel, Dunford kept an active gig life, to the chagrin of Schola administration. Instead of pursuing another degree, he returned to Paris at the age of 21 to study at, as Smith termed it in an email, “the School of Life.” In those years, he played on stages, in opera pits, and on a staggering number of albums all around Europe. Whether he’s plucking gossamer harmonics below his parents’ Marin Marais, making wolf noises from the pit of Hervé Niquet’s uproarious reinterpretation of Henry Purcell’s King Arthur, or improvising diminutions over John Dowland songs on his inaugural solo album, you always know it’s him.

All roads lead to Thiré

The Paris gig scene taught Dunford that the music world is as much business as art, especially as he emerged as a leading soloist on his instrument. “You have to learn how to deal with agents, production people, record labels,” he said. “You need to be careful with your time, because the more time goes, the more you know exactly what you want to do.”

Indeed, Dunford has gotten to that enviable point where he can choose his gigs carefully. Between solo recital tours, he still plays and records with Ensemble Pygmalion, enjoying a featured spot on the recent Bach-Handel album headlined by astounding soprano Sabine Devieilhe. Across the English Channel, he’s recently made a new friend in titan conductor John Eliot Gardiner, with whom he’s begun to tour. And he sometimes joins Arcangelo, the ensemble of harpsichordist, conductor, and pal Jonathan Cohen — two glorious volumes of Buxtehude trio sonatas have sprung from that collaboration. (Cohen becomes Boston’s Handel and Haydn Society artistic director in the fall.)

But the ensemble with whom Dunford appears most often — apart from his own — is Les Arts Florissants (or lovingly, Arts Flo), the trailblazing French group that celebrated its 40th anniversary shortly before the pandemic. Cohen, one of the group’s associate conductors, recommended the lutenist to U.S.-born and -trained founder William Christie. Their first major collaboration: a revival of Lully’s Atys, reportedly Louis XIV’s favorite opera, which received its modern premiere, under Christie, around the time Dunford was born.

“I was instantly amazed by Christie’s presence and music making,” said Dunford. “He’s so theatrical, and so emotionally involved in the music. It’s actually magic — he can just stand in front of the orchestra, and his emotion will be so palpable that the entire group will sound golden.”

Christie says that their connection was immediate, despite the four-and-a-half-decade age difference. “It was telepathy,” he said. “We suddenly realized we were doing exactly the same thing in our harmonic progressions and melodic accompaniment. Thomas is one of the best of the young generation — I’d almost be ready to call him a genius.” (Perhaps that label will come with age.)

Dunford is at home in any Arts Flo configuration. He often sits front and center in large choral-orchestral projects: his twiddles livened ensemble favorite “Les sauvages” (from Rameau’s Les indes galantes) at their recent anniversary concert. He’s explored chamber music from all corners of Baroque Europe and toured North America with Christie and mezzo-soprano Lea Desandre — Dunford’s fiancée — as “Les Arts Florissants Trio” in 2022. (The promotional materials for those concerts screamed “family vacation.”)

Dunford and Desandre have Arts Flo to thank for their upcoming nuptials. In Dunford’s world, many roads lead back to the small town of Thiré, in the Vendée region of western France, where Christie transformed his sprawling estate into a miniature Versailles, formal gardens and all. The young couple met there during the summer of 2015, and over eight-concert days and long nights of beers and Beatles, they clicked. Their relationship is as professional as it is romantic. They will marry this September.

‘He never falls into habit’

As a young player in the gig economy, Dunford always thought about how he could lead differently. He wanted to return to his ardent passion for music, shunting business obligations to the extent possible. Above all, he wanted a group that could reach beyond the confines of “early music.”

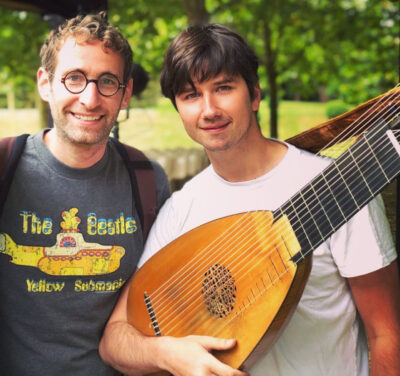

In 2018, Dunford founded Jupiter, the name a tribute to his longtime passion for astronomy and mythology. Arm-waving was not his style, he decided — he’d rather lead from his instrument, let everyone contribute different skills, and assemble a rotating membership from all corners of his musical life. Top Parisian freelancers. Juilliard alumni he had met in Thiré. Fellow it-boy soloists — most notably Jean Rondeau, Dunford’s approximate wild-child counterpart in the harpsichord world. And at the center of it all: his musical soulmate, Desandre.

With their first album (released in 2019 on Alpha Classics), Jupiter sought to rid Vivaldi of his snobby, tie-and-tails baggage. “Vivaldi used to play in front of orchestras that knew his music — and they were rocking out!” Dunford said. And no one rocks Vivaldi harder than Jupiter. Desandre’s agitata arias romp and rollick with pure fire; her slower arias are chillingly, glacially gorgeous. Dunford and a couple of friends take virtuosic turns in the concerto hotseat, roused by the electricity of the ensemble that surrounds them.

On Jupiter’s auspicious March 2022 tour, the ensemble made four U.S. stops, starting in San Francisco and including a Carnegie Hall debut. They reprised the Vivaldi program in another dozen North American venues in March 2023.

Avery Fisher Career Grant winner and Juilliard graduate Rachell Ellen Wong, who played first violin on Jupiter’s inaugural U.S. tour, says Dunford’s mind is constantly percolating with music. “Even after we’ve done multiple concerts, he’ll still be thinking about ways to experiment,” she said with a sense of awe. “He never falls into a habit.”

Wong was one of several Juilliard-to-Thiré connections in the touring ensemble. Dunford says that the school’s youthful vigor is shaping early-music spheres abroad as well as in the U.S. “In Europe, we get some high technical level players,” he said. “But Juilliard has this cool energy, and there’s been an evolution of creativity and openness over the years that’s thrilling.”

‘Juilliard has this cool energy, and there’s been an evolution of creativity and openness that’s thrilling’

In Europe, the Vivaldi album was a launching point. Suddenly, Jupiter appeared all over France’s television and radio waves. Erato Records signed the group in 2020. The next year, Jupiter and Desandre released a second album, dedicated to the mythical Greek warrior women known as Amazons. And at the end of 2022, Jupiter released a Handel album of the composer’s English solos and duets — Dunford’s longtime recital partner, the countertenor Iestyn Davies, joined Desandre in front of the ensemble.

“Suddenly you think hey, wow, that’s a big snowball,” Dunford chuckled. He admits that his ideas are at times outsized. “I’m not the type of guy who’s very realistic. So I dream of projects, and then some amazing realistic people help me with the organization and finances and all that stuff.”

Jupiter’s next major project leaps several centuries to Hollywood’s Golden Age: a Julie Andrews program, staged for opera houses in both Paris and Rouen. It’ll be the ensemble’s first orchestral project, with three string players per part (instruments strung in Baroque-appropriate gut), and a small jazz combo. But Dunford is also ready to branch into the opera pit. He wants to start with John Blow’s Venus and Adonis, which he led for Washington, D.C.’s Opera Lafayette in 2019 — with Desandre, naturally, in the title role.

A Hard Day’s Night

Dunford has a knack for improvisation, even outside of the early-music sphere. In high school, he would tote his lute to play with his friends at jazz festivals around France. (Pat Metheny once approached him to inquire after his “cool guitar.”) After long days of concertizing, the lutenist often finds himself riffing wherever it’s convenient — hotel rooms, bars, William Christie’s Thiré pub shack. It’s one way he forges bonds with the musicians that surround him, and occasionally, those bonds lead to great future projects.

One was bassist, composer, and Juilliard grad-turned-professor Douglas Balliett, whom Dunford met during the inaugural Thiré festival in 2011. According to Balliett, they bonded over a spontaneous bit of Maynard Ferguson’s jazz standard “Chameleon.” The kinship was instant.

“He understands music in very much the same way that I do,” said Balliett, who was also a founding member of Jupiter. “We share this sort of integrated approach — a basic understanding of harmony and structure that gives you the freedom to improvise and create together.”

The two began to jam regularly whenever they found themselves in the same city, as much an American indie-pop duo as a major force on the French early-music scene. Their first song, “Under The Willow Tree” (later repurposed to “Under Bill Christie’s Tree”), originated on a languid afternoon in Central Park. During a month-long European tour of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera with Christie and Arts Flo, they continued to hone their collective voice both onstage and off.

The duo wrote the track that capped Jupiter’s Vivaldi album, “We Are The Ocean,” in the bar of a Berlin hotel, after a performance of Beggar’s Opera. The song is a lowkey digestif to an album full of activity, the tender vocals of the Desandre-Dunford-Balliet trio showing a hint of close-miked rasp. Its center section is a jazz breakdown to rival any club-trotting combo; when the group performs “Ocean” as an encore, Dunford plays meet-the-band over Balliett’s funky bass line, allowing each player in the ensemble to add their own signature flourish.

It’s now tradition to end Jupiter albums with a Dunford-Balliett special. On the recent Handel album, the group finished with “That’s So You,” whose name, Balliett says, was chosen by a Ouija board in Denmark. The song came together in bits — they started the music in Geneva, the lyrics in Versailles. In its finished form, “That’s So You” occupied one of Jupiter’s slots on the TV show Le grand échiquier, a showcase of France’s greatest young talent.

“It’s very funny to me that these songs which were born out of beers and bar trips are now getting played on TV and in concert halls all around the world,” Balliett said. “Touching, but funny.”

Unsurprisingly, Balliett and Dunford bond over their shared love of music — not only Monteverdi and Purcell, but also jazz, Bob Dylan, and most of all, the Beatles. Dunford calls Balliett a leading expert on the British-invasion icons, to the extent that he teaches a Juilliard course on their music. Both profess that their relationship mirrors that of Paul McCartney and John Lennon: Dunford has Paul’s wild creative streak, while Balliett is the cynical realist (and the primary lyricist). They’ll sometimes even address each other by the names of their respective Beatle in the studio.

“It was so satisfying when we met — we just fell into this natural musical friendship,” said Balliett. “I was always looking for the Paul to my John.” He paused, chuckling. “And Thomas is the only person I’ve ever met that can carry a party with a lute!”

‘Thomas is the only person I’ve ever met that can carry a party with a lute!’

It seems that Dunford is inching closer to his Beatles dreams by the day. During the height of lockdown, Apple Music approached him for an album of original pop songs, part of their ongoing series of “Home Sessions” that prominent artists recorded from the confines of their houses. Apple agreed to finance any recording engineer that Dunford wished, so he chose Abbey Road’s Sam Okell, most famous for his recent remasters of the Beatles’ discography. The Apple Music release is scheduled for the spring of 2023.

When I talked to Dunford, he had just returned from back-to-back tours in North America and Europe. During the pandemic, he and Desandre hunkered down at her parents’ home in the Paris suburbs. Now that the scene has come surging back, Dunford admits that his current schedule of a concert every day or two is too much. Yet every time he sits down with his lute, the woes of the world seem to wash away: “Playing the music is the easy part for me. It’s just a joyful moment, and I always love it.”

It’s that pure joy that Dunford aims to convey to his audiences. “Time is precious. We have limited time here on earth,” he said. “And when you play, for example, Bach’s music, it’s universal. The room becomes a better place for everyone — more compassionate, more loving, happier. You get a little bit of your ideal society in a small room, and that’s what makes it worth doing.”

Emery Kerekes is a writer and arts administrator. Winner of the 2022 Rubin Prize in Music Criticism, he is a founding editor and contributor for Which Sinfonia, and his byline has appeared in Musical America, Opera News, and beyond. He works in The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of Live Arts.