by Alison DeSimone

Published August 6, 2023

New Perspectives on Handel’s Music: Essays in Honour of Donald Burrows. David Vickers, editor. The Boydell Press, 2022. 453 pages.

As far as essay collections go these days, Festschriften are a rare breed. Academic cynics claim that these volumes — a set of essays written around a theme, in honor of a notable scholar in that area — are miscellany repositories for articles and chapters that could not otherwise be published. I, however, study miscellanies, and therefore appreciate the genre precisely because of the multitude of different subjects that can all be found in a single volume. And while academic presses are less and less likely to publish Festschriften in the 21st century, it is significant that The Boydell Press supported the publication of New Perspectives on Handel’s Music: Essays in Honour of Donald Burrows.

Their beautiful volume properly commemorates a scholar who has done so much for Handel scholarship and performance during his long career. Moreover, the 20 contributors to the book — all of whom offer a variety of scholarly perspectives — come together to praise someone who trained many of them, and whose work influenced all of them. As far as exciting new scholarship on Handel goes, this Festschrift is the place to find it.

Their beautiful volume properly commemorates a scholar who has done so much for Handel scholarship and performance during his long career. Moreover, the 20 contributors to the book — all of whom offer a variety of scholarly perspectives — come together to praise someone who trained many of them, and whose work influenced all of them. As far as exciting new scholarship on Handel goes, this Festschrift is the place to find it.

David Vickers, as editor of the collection, had the Herculean task of making sense of miscellany. As he writes in his introduction (or “overture” in his words), the book is organized into three acts, paying tribute to Handel’s opera and oratorio structures.

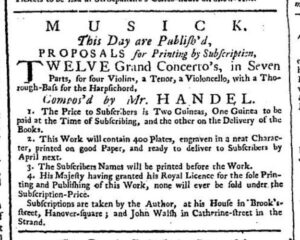

The first six chapters center on “Handel’s Music and Creative Practices,” and the topics run the gamut from early Handelian operas (including Almira, his first), to compositional practices, to Handel’s oratorios. Chapters include “‘Almire regiere’: Some Reflections on the First Aria in Handel’s First Opera” (David Kimbell); “Il pastor fido by Guarini (1585) and Handel (1712): From tragicommedia pastorale to dramma per musica” (Suzana Ograjenšek); “Late or Soon? Cadential Timing in the Continuo Recitatives of Handel and His Contemporaries” (John Roberts); “Handel’s Bilingual Versions of Esther and Deborah, 1734-1737” (David Vickers); “Handel’s Compositional Process in the Creation of the Grand Concertos, Op. 6” (Silas Wollston); and “The London Revisions of Handel’s First Roman Oratorio: Il trionfo del Tempo e della Verità (1737) and The Triumph of Time and Truth (1757)” (Matthew Gardner).

Act II comprises essays on “Sources, Documents, and Attributions,” which draw from the Handel Documents series, an extremely important collection of primary source material relating to Handel (and edited by Burrows). These contributions all use scores and archival documents as a starting place to explore little mysteries surrounding aspects of performance, the history of publication, and Handel’s own life. Chapters include “Handel’s Continuo Cantatas: Problems of Authenticity, Classification and Chronology” (Andrew V. Jones); “When and Why Did Handel Replace his Conducting Scores?” (Hans Dieter Clausen); “Handel, the Duke of Chandos, and Investing in the Royal African Company” (David Hunter); “Handel and Comus at Exton” (Colin Timms); “Wordbooks for Handel’s Oratorios, Especially Joseph and his Brethren and Hercules: Copyright and Production” (Leslie M.M. Robarts); and “New Music by Handel for Horns?” (Anthony Hicks, rev. Colin Timms after Hicks’s death).

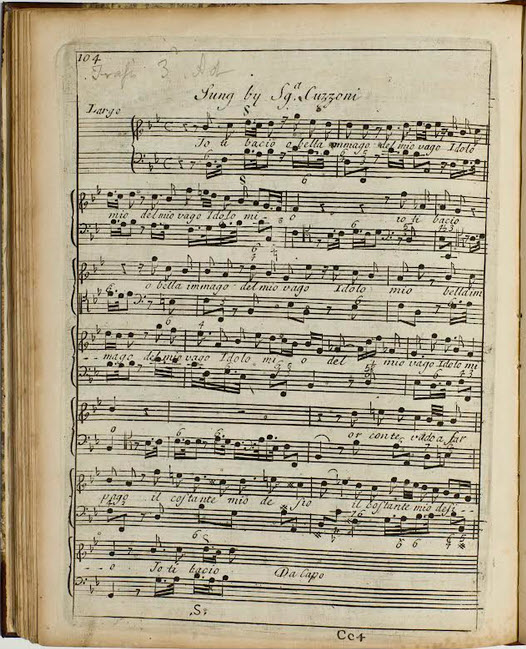

Finally, Act III focuses on “Context and Reception,” with chapters on Bach, Handel’s singers, places of performance, and specific works. The entire book reinforces Handel’s successful diversity as a composer and a musician, as well as the richness and depth of Burrows’s musical interests and scholarly contributions throughout his career. Chapters include “Bach and Handel: Differences within a Common Culture of Musical Invention” (John Butt); “Le rivale regine: Faustin and Cuzzoni in Satirical Engravings, Literature, and Opera in the 1720s and 1730s” (Richard G. King); “Charles Jennens Revisited” (Ruth Smith); “‘O Come, Let us Sing unto the Lord’: Performances of the Cannons Anthems during Handel’s Lifetime” (Graydon Beeks); “Charity Performances of Handel’s Works in Eighteenth-Century Dublin” (Tríona O’Hanlon); “Early Keepers of the Flame: Vanneschi (and Handel) at the Opera” (Michael Burden); “Revamped Handel: the Content and Context of his So-Called ‘Miserere’” (H. Diack Johnstone); and “Handel’s ‘celebrated Largo’: Remarks on the Reception History of ‘Ombra mai fu’” (Annette Landgraf).

I will highlight a few chapters that I find particularly fascinating, although that is by no means a judgment on essays not mentioned. These are simply a few of the essays that I look forward to assigning in classes because of the questions they pose, the documents they interrogate, or the methods they utilize. I’ve selected one from each “act” in order to show the breadth of the volume’s content across its 453 pages.

In Act I, John Roberts offers a concise and useful discussion of cadential timings in Handel’s recitatives (and those of other early 18th-century composers). Roberts provides numerous examples from treatises to reconstruct what continues to be an age-old question: Do we place the continuo’s cadence after the singer cadences the melody, or does it correspond to the singer’s cadence? I have been asked this question many times by colleagues and students, and as Roberts’s chapter shows, there is no one answer in the 18th century. Thankfully, Roberts presents significant evidence that if we follow what Handel wrote in his autographs, we should be fine. The chapter’s depth is impressive (especially for only 14 pages with lots of musical examples), and the performance practice implications benefit performers and scholars alike.

David Hunter offers a chapter based on other types of materials: in his case, documents showing that Handel owned and sold some stock in the Royal African Company twice during his life. Hunter’s chapter appears as part of Act II and contextualizes Handel’s investment within a broader picture of patronage by focusing on James Brydges, Duke of Chandos, for whom Handel worked in the 1710s. Hunter acknowledges that Handel may not have purposefully invested in these shares; rather, they may have been a means of payment for his work at Cannons, the duke’s estate. Ultimately, Hunter’s tantalizing questions and investigation leave room for potential further studies — in the classroom, or in musicology Master’s thesis or Ph.D. dissertations — on the economics of the slave trade in 18th-century Britain and its intersections with music history.

Handel’s name often appears alongside another German composer born in 1685, Johann Sebastian Bach. In Act III, John Butt usefully tackles a comparison between Handel and Bach, focusing on how their early lives and musical training differed and therefore sparked different career paths. However, Butt also acknowledges that the two composers began with the same musical materials: “[Bach and Handel] retained the principles of a surprisingly archaic composing culture, and that their individuality and success as composers lay partly in the reaction between these principles and the newer elements they encountered in musical practice.” Butt investigates nodes of similarity in Bach and Handel’s lives, and then explores how their social, musical, political, and religious circumstances led to vastly different outcomes. Butt’s chapter is especially important in its continued contextualization of musical borrowing, something at issue for both Bach and Handel.

While I wish I could document the book in its entirety, I urge those who read this review to go out and get yourself a copy of New Perspectives on Handel’s Music: Essays in Honour of Donald Burrows. Read separately, each chapter is intriguing, with nuggets of exciting new approaches and assessments of Handel’s music. Taken together, the book is a testament to Donald Burrows’ extraordinary legacy as a scholar, and the networks of performers and academics whose lives he has touched. I do not know a more dedicated Handel enthusiast than Burrows, and I am thrilled that David Vickers and his contributors have paid homage to such a legacy.

Alison DeSimone is Associate Professor of Musicology at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, where she specializes in music of 18th-century Britain. She has published books with Cambridge University Press and Clemson University Press, and her articles can be found in Eighteenth-Century Music, Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture, Journal of Musicological Research, A-R Online Anthology, Händel-Jahrbuch, and Early Modern Women.