by Aaron Keebaugh

Published September 4, 2023

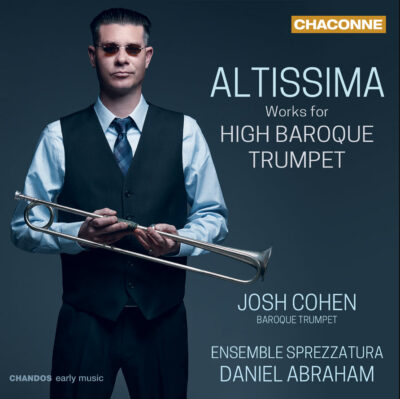

Altissima: Works for High Baroque Trumpet. Josh Cohen, trumpet, with Ensemble Sprezzatura. Chandos CHAN 0828

For all of its ebullience, the Baroque trumpet can often be limited in expressive range. Trills and mordents may deliver zest to the melody. But the usual repertoire rarely calls for the trumpeter to languish in the moment or relay much delicacy beyond pomp and ceremony.

Fortunately, Ensemble Sprezzatura and trumpeter Josh Cohen bring together regal flair and expressive grace with Altissima, a recent disc that explores the varied colors and dimensions of the high Baroque trumpet. At once playful, lyrical, and technically brilliant, these performances make an ideal introduction to myriad trumpeting styles through mostly little-heard repertoire.

Much of the program calls for Cohen to perform musical acrobatics in the extreme upper register. He handles each challenge fluently. Lip trills are immaculate, articulations crisp as spring water. Yet in Georg Philipp Telemann’s Concerto TWV 43:D7, these figures always serve the larger picture. Strict tempos in the final movement allow for the syncopations to come off with force. Throughout, the ensemble blankets him in sounds that range from warmth to customary grandeur.

That stylistic sweep is evident in Christoph Graupner’s Concerto GWV 308. Completed in 1744, this work leans towards stile galant elegance. Cohen channels that sensitivity through embellishments that are so pristine they could match that of a modern piccolo trumpet.

Cohen also makes the simplest gestures of Romanus Weichlein’s Sonata à 8, Op. 1, No. 1, sound resplendent. He brings palpable weight to every phrase, with arpeggios that wax and wane, coalesce in long-breathed lyricism, and build urgently to resolution. Even the fanfares of the second carry the momentum forward. Meanwhile, Ensemble Sprezzatura, directed by Daniel Abraham, avoids the traps suggested by the marked “Con discretione” — indeed, nothing about this performance feels timid or tentative.

That’s especially true in the works that pit the trumpet as an accompanying voice. In Gottfried Finger’s Sonata in C major, Cohen and oboists Margaret Owens and Geoffrey Burgess generate as much mystery as verve. Yet they also work well in tandem: Cohen’s bold declamation naturally gives way to the oboes’ aching sweetness, like a mighty oak casting shade over a weeping willow. Johann Samuel Endler’s Sinfonia à 7 brims with terpsichorean zeal. While it may lack the textural nuances of Bach’s orchestral suites, this score from 1749 is put across with enough elan to make it lilt. Cohen and the musicians do the same with Capel Bond’s Concerto No. 1, where stately opening figures scatter into a finely woven fugue. Cohen provides splashes of vibrant color.

Beyond poise and polish, the rest of the performances are simply fun to experience. Philipp Jakob Rittler’s Ciaccona à 7 is as much a play on rhythm as varied textures. Cohen and company land heavily on every down beat for a toe-tapping groove. And the familiar strains of Gottfried Reicha’s fanfare Abblasen bring to the fore everything the Baroque trumpet can be — powerful, dexterous, and, most of all, a sound of sheer joy.

Aaron Keebaugh has written for The Musical Times, Corymbus, The Classical Review, and The Arts Fuse, for which he serves as regular classical critic. A musicologist, he teaches at North Shore Community College in Danvers, Mass.