by Patricia García Gil

Published September 11, 2023

Maria Antonia Palacios and Maria Guadalupe Mayner: their private notebooks have become a treasure house of lost music

Early music in Latin America encompasses rich and diverse traditions that reflect the mixing of European, African, and Indigenous musical styles and practices. During the colonial period, from the early conquests of the Americas through the 18th and 19th centuries, the cultural transfer between Iberia and Latin America was typically asymmetrical, influenced by power dynamics. European musical traditions, particularly those of Spain, were brought to Latin America by colonizers and missionaries. Music of the Catholic Church was prominent, including Gregorian chants, polyphonic choral music, and hymns, and many of the most active composers during the 17th and 18th centuries were priests. Sacred music not only served to express religious beliefs but had a greater overall impact, to reinforce the dominance of the conquerors. Not surprisingly, it is mostly Christian religious music of the colonial period that has been preserved and studied.

But this was not the only cultural and political situation in which music was composed or performed. For scholars and performers, the many difficulties finding music created under these circumstances brings up questions about whether race, gender, and class were factors that led to the obscurity (or loss) of secular music produced during this period. Certainly some musicians’ capacities — beyond composition and performance — might have contributed toward the preservation of non-religious music composed and played at the time.

As Enlightenment principles were spreading across Europe and into the Americas, a new power elite arose in service to the monarchy, although not necessarily aristocrats. It was an elite that now included women from privileged families who acted frequently as patronesses and hostesses.

As described in The Routledge Companion to the Hispanic Enlightenment, the movement circulated through academies, universities, private tertulias (salons), and periodical publications that were widely distributed across Iberia and the Americas.

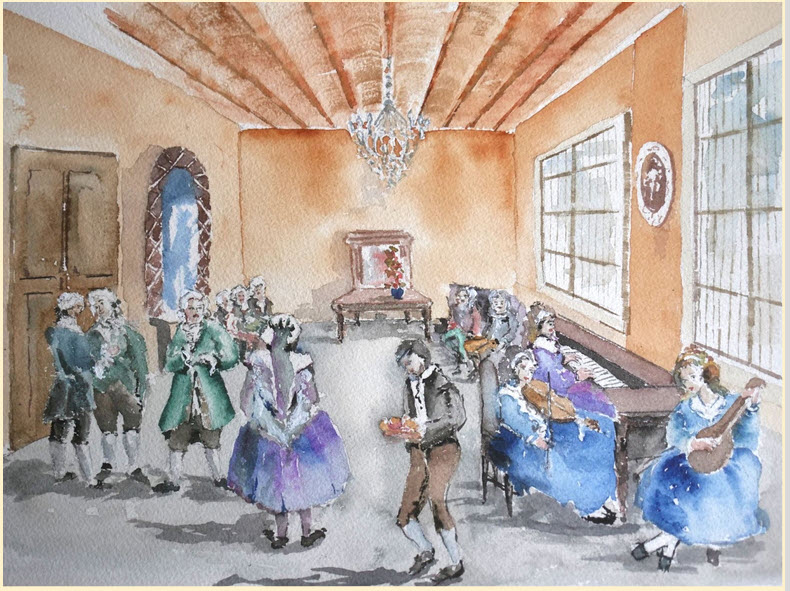

Musical performances, commonly held in private spaces of a courtly, aristocratic, or sacred nature, led toward what we know today as a public concert, although the format was quite different. In addition, the new elites acted as patrons for musicians, hosted concerts, and held great music libraries. Musicians no longer had to be servants of the patrons and were hired with no exclusivity.

As Asunción Lavrin explains in her essay “Women in Spanish American Colonial Society,” for most of the colonial period, women had very limited access to education, and it was based in the principles of Catholicism “with stress on the preservation of honor and feminine patterns of behavior.” Yet some girls who belonged to the socio-economic elite received basic training in reading, writing, and music, at home or in convents, and “the acceptance towards the end of the colonial period, of the idea that it was desirable to educate all women was one of the most significant changes in social attitudes about women.”

Toward the end of the 18th century, public and private schools started to spread, opening their doors to girls of all social classes. Institutions like Mexico’s School of Santa Rosa of Valladolid, the Convent of the Santísima Trinidad de Puebla, and the School of Las Vizcainas, provided musical education to women and preserved the music of Spanish and Latin American composers, unfortunately keeping many of the authors anonymous, perhaps due to their gender.

Both in convents and in schools, researchers have found manuscript anthologies designed for the private use of women such as the “Sonatas del uso de Sor María Juana de Guadalupe,” a nun at Convento de la Santísima Trinidad, or the “Manuscript of Mariana Vasques,” of unknown origin, that includes sonatas and dances. Some of these manuscripts have been described by Javier Marín-López (in “Música, nobleza y vida cotidiana en la Hispanoamérica del siglo XVIII: hacia un replanteamiento,” International Musicological Society: Acta Musicologica.)

Most of these compilations contain non-sacred keyboard music, including pieces specifically written for the fortepiano, reflecting the advancement of domestic music-making in varied social spheres that came along with the Enlightenment. The women for whom these compilations were destined were often very skillful performers, and furthermore, they knew how to write music and were able to preserve it.

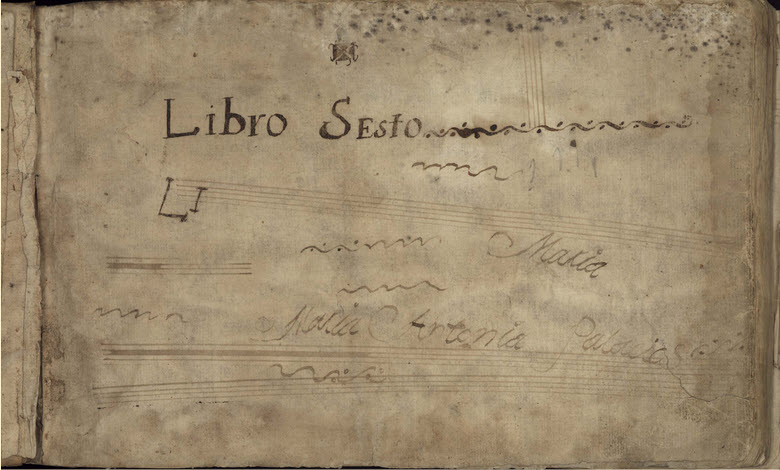

One notable example is the case of Maria Antonia Palacios, whose name appears on the front page of a manuscript titled Libro Sesto de Maria Antonia Palacios. This compilation, from around 1790, was discovered by the musicologist Guillermo Marchant in a religious Chilean institution where it had been unseen until 1970. The ongoing research indicates that its purpose was to be performed by the owner, due to the kind of compositions that it comprises. The label “Sesto” (meaning sixth) could imply the existence of a series of these anthologies, although no others have been found as yet. The hand-copied book is a compilation of compositions attributed to Haydn, Pleyel (very likely Ignaz, the fortepiano builder), some anonymous (perhaps local?) composers, as well as Spanish composers such as Juan Capistrano Coley y Embid, whose name appears often. Intriguingly, according to a 2016 Répertoire International des Sources Musicales (RISM) newsletter, the “first movement of Haydn’s Piano Sonata in C major, Hob.XVI:35, is notated in the manuscript, but this Chilean source is not known in Anthony Hoboken’s thematic catalog.”

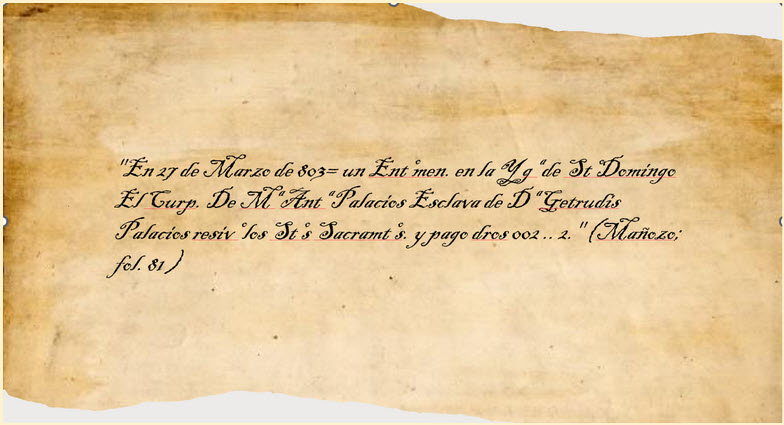

Marchant examined the question of Maria Antonia Palacios’ identity. By contrasting documents from different Chilean archives, including the archiepiscopate and a very plausible death certificate, he pushes aside the idea that she had been Spanish. Instead, he proposes that she had been an enslaved Black woman with musical knowledge and was somehow connected to a church as an organist.

Of the 165 works copied into the manuscript, 108 were clearly written for organ and most likely were intended for liturgical use, while six are specifically composed for the pianoforte, eight for salterio, and the remaining 43 could be performed on any of these keyboard instruments.

A remarkable discovery is the set six minuets and two marches for salterio by Pleyel, which are only found in this manuscript, as well as other Spanish composers’ works that seem to be absent from any archive in Spain. Joaquin Castillon’s Sonatas para Pianoforte o Clavecín, dated 1781, is one source that points to when the fortepiano started to be taught in Spain.

“Virtuosas del teclado”

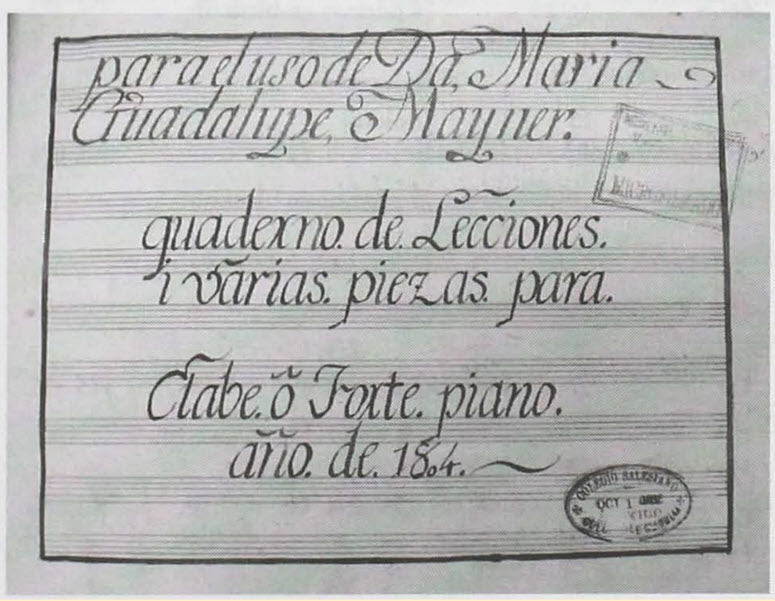

Another curious example is the case of Maria Guadalupe Mayner, whose origin remains unknown. Her name appeared on the front page of the Quaderno de lecciones i varias piezas para clabe o forte piano para el uso de Da. Maria Guadalupe Mayner.

Dated 1804, this “lesson notebook” is preserved in the Library Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada in Mexico City. It is a manuscript compilation of 50 musical works, including sonatas, dances, songs, and exercises. One notable piece is the “Sonata quinta del señor aydem” — once attributed to Haydn, although it is not written in Haydn’s style and does not appear in the composer’s catalog. (In addition, between pages 83-158, there are eight two-movement sonatas and two one-movement sonatas. Haydn’s presumed authorship had been revoked by later musicological studies.)

Also included in Mayner’s notebook is “Las siete palabras, de Joseph Haydn,” a transcription of Haydn’s famous orchestral work Seven Last Words of Our Saviour on the Cross, which had been commissioned for the 1786 Good Friday service in Cadiz, Spain; selections of the Four Sonatas Op. 5 for Violin and Piano by Luigi Boccherini, although his name is not specified; the Minuet for 4 Hands written by Marquesa de Vivanco (also of unknown origin, or perhaps another name for Mrs. Mayner herself?); a set of Manuel Antonio del Corral’s patriotic songs, inspired by the War of Independence against the French invasion in Spain by Napoleon’s brother (“A las armas cored,” “Patriotas Españoles,” and “La patria oprimida”); and the “Minué variado” composed by [Manuel] Aldana (1758-1810), a Mexican violinist, fortepianist, and composer who worked at Mexico City Cathedral and at the Teatro Coliseo. (It is not clear, however, if the composer was Aldana father or son.)

Some of the exercises in Mayner’s lesson notebook seem to teach theory and basic keyboard skills, which is a reason why this book could be considered a teaching method; however, the difficulty of the other pieces and the fact that sonatas outnumber the other genres — as well as the second part of the notebook’s title “…for the use of Mrs. Maria Guadalupe Mayner from Mexico” — suggest a personal collection for the use of this lady, perhaps hand-copied by her between the dates that appear on some of its pages: 1804 and 1814.

On the other hand, as Javier Marin-Lopez points out in the article “Música, nobleza y vida cotidiana en la Hispanoamérica del siglo XVIII: hacia un replanteamiento,” the first part of the notebook’s title “Quaderno de lecciones i varias piezas para clabe o forte piano…” shows how playing the harpsichord and the fortepiano was common and desired for women at the time.

Toward the end of the viceroyalty of Iberian colonialism in the Americas, professional musicians were generally men, although but there are a few notable references to women as “virtuosas del teclado,” such as “Doña N. Terri” (cited in Mexico journal), or “Dorotea Losada” (cited by Elizaga).

It was customary for women to own instruments and organize tertulias (salons), and documents like the compilations associated with Maria Antonia Palacios and Maria Guadalupe Mayner show the kind of repertoire that was performed during these events.

Manuscripts such as these reveal wonderful music and they encourage the realization for musicians and historians of the importance of the role that these women played in the preservation of Spanish and Latin American musical heritage. There are still many research gaps around secular musical life of this period that will hopefully intrigue performers and scholars to continue delving into it. There must be more examples of other women whose role has been overlooked, and whose legacy would enrich and enlarge our knowledge of music history.