by Anne E. Johnson

Published October 2, 2023

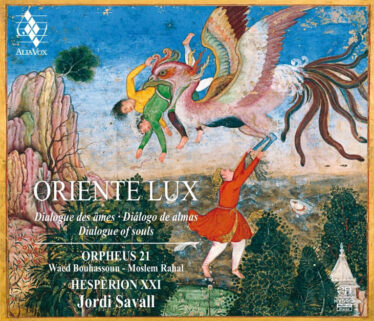

Oriente Lux: Dialogue of Souls. Hespèrion XXI and Orpheus 21, led by Jordi Savall. Two-CD set. Alia Vox AVSA9954

In 2016, star viola da gambist Jordi Savall joined with two Syrian musicians — singer and oud (lute) player Waed Bouhassoun and ney (end-blown flute) player Moslem Rahal — to assemble a group of immigrant musicians for a multicultural ensemble with a far-sighted purpose: Beyond simply giving the musicians work, the idea was to have them teach refugee children, helping to ensure that their own musical traditions were not lost.

The result was the organization Orpheus 21, the world-music sister of Savall’s early-music ensemble Hespèrion XXI. In its ranks are 20 singers and instrumentalists representing Kurdish, Syrian, Bengali, Sudanese, Turkish, Moroccan, Afghan, and Armenian music. Both these ensembles share a fundamental mission: to preserve and revive precious music from human history. Savall paired both groups for performances across the 2017-18 seasons, one of which is captured on the live recording Oriente Lux: Dialogue of Souls.

The title refers to looking East for the light of creativity as well as reaching East to help those in need. Savall believes that “classical music is rooted in folk traditions,” and never has that tenet been more clearly illustrated. Here West is rooted in East, as in their take on Michael Praetorius’ “Canarios” from his 1612 Terpsichore. Savall has couched this German work in sounds of the East; a long-improvised meditation on the oud mesmerizes the listener before the whole band comes in with the brief Praetorius, swirling in 6/8, lit with the bright attack of percussion.

The Praetorius is merely a bridge to the next tune, a religious song — in the same tempo and meter — from the Kurdish Yazidi tradition. Ruşan Filiztek’s vocal line, ornamented with yodel-like flips, lies over a repeating stepwise figure in the instruments.

Since the purpose of the recording is to bridge gaps, more specific information about the instruments playing each track would have been welcome. Not all of us can hear the difference between an oud and a saz, for example. Yet Savall’s theory of the interconnectedness of traditions keeps proving itself. There is much that is recognizable in every track, even when the rhythms, harmonies, and instrumental timbres might be less familiar to some listeners than, say, shawms and rebecs.

Many fans of European Medieval music will know the sounds of the Sephardic tradition, which Savall has spent significant effort mastering over the past three decades. There are two examples of Sephardic music here. Rebal Alkhodari sings the haunting “La rosa enflorece” along with ghostly female backup voices. “El Rey Nimrod,” an Israeli instrumental, begins in the meandering style of a fantasia, glistening with plucked strings, before tightening into a syncopated dance rhythm.

It’s tempting to forget complex and seemingly hopeless political reality when an Iranian piece like “Al-bint el shalabiyya” can share so much, stylistically, with “El Rey Nimrod.” Surely that blurring of borders (geographical, religious, cultural) is the whole point of this project.

There is no end of these sonic treats. Ruşan Filiztek, accompanied only by dense layers of percussion, sings the almost rap-like “Mîrkut,” from his native Kurdish Turkey. Syrian singer Abo Gabi and “tout les musiciens” calm the mind with a classical Arab song type called a muwashshah.

Many of the musicians and pieces are Syrian. Savall dedicated these concerts to refugees of the war in Syria. As grim as that situation may be, it is impossible not to feel a glimmer of hope when listening to the album’s finale. Everyone comes together to sing and play the rousing “‘Al maya, ‘Al maya,” with the audience clapping along.

Savall has performed and recorded with such quality for so long that one almost takes for granted the skill behind these arrangements, perfectly balancing technical precision with a sense of vibrant tradition. Much of the credit goes to Waed Bouhassoun and Moslem Rahal, who helped hold the Eastern end of this great bridge up to Savall’s high standards.

Anne E. Johnson is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn. Her arts journalism has appeared in the New York Times, Classical Voice North America, Chicago On the Aisle, and Copper: The Journal of Music and Audio. For many years she taught music history and theory in the Extension Division of Mannes School of Music.