by Paul Corneilson

Published February 12, 2024

Women and Musical Salons in the Enlightenment by Rebecca Cypess. University of Chicago Press, 2023. 365 pages.

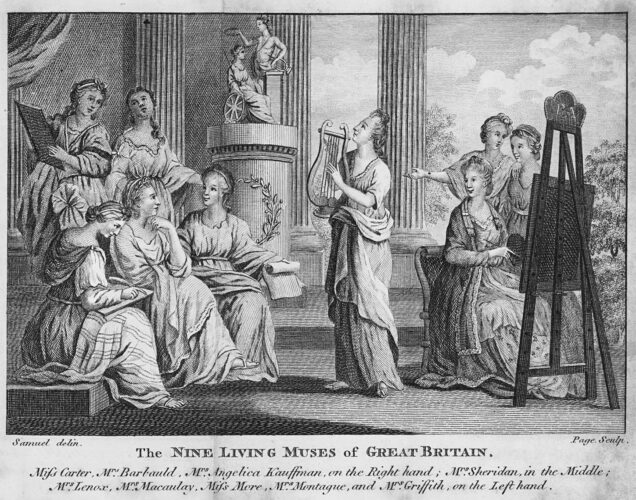

Musical salons in the late 18th century, which were mostly held in private homes and hosted by accomplished women, have often been treated as “fringe events” in music histories. Rebecca Cypess, however, has put them front and center in her engaging new book, Women and Musical Salons in the Enlightenment. She focuses on five women who not only promoted a variety of composers, writers, and painters, but who were often creative artists themselves: Anne-Louise Boyvin d’Hardancourt Brillon de Jouy in Paris; Marianna Martines in Vienna; Sara Levy in Berlin; Angelica Kaufmann in Rome; and Elizabeth Graeme in Philadelphia.

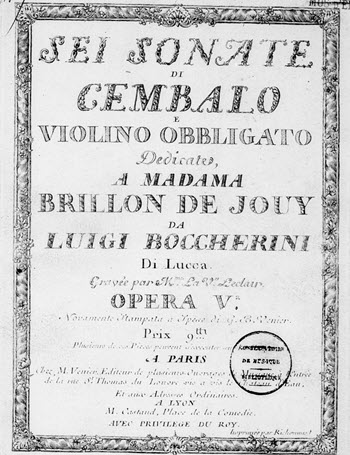

Rather than simply telling the life stories of these salonnières, Cypess takes us into their salons and discusses the music they wrote and performed, as well as some of the instruments they played. Madame Brillon, for instance, used an English square piano that she purchased through Johann Christian Bach to perform some of her own music. Apparently, her playing inspired Luigi Boccherini to write a set of accompanied sonatas, his Opus 5, which he dedicated to her. I’m not sure this rises to the level of “multiple authorship” (a term introduced by Emily Green in her book, Dedicating Music, 1785–1850), but Cypess makes a good case that Madame Brillon collaborated with, or influenced, Boccherini in how he wrote for the keyboard. Cypess argues that Madame Brillon’s primary aesthetic was “ephemera” and that her own music reflects the harp-like sound of the square piano.(Many of the musical examples are performed by Cypess herself, taken from recordings by the Raritan Players.)

Charles Burney wrote about some of the women whom he met on his travels in Europe while collecting data for his History of Music. Cypess echoes Matthew Head (in Sovereign Feminine: Music and Gender in Eighteenth-Century Germany) in pointing out that Burney tends to praise the women he discusses a little too fulsomely — perhaps because he had so many talented daughters? — but these women often attracted other famous men who served as mentors or friends. Marianna Martines was a pupil of Metastasio, the imperial court poet, and shared living accommodations with Joseph Haydn as well. Burney makes it clear that Martines and Metastasio were often together, and that Martines was an excellent interpreter of Metastasio’s poetry. Cypess discusses a few of the arias and cantatas that Martines set, and comes to the conclusion that these were above average works.

Sara Levy belongs to the generation between Moses Mendelssohn and Felix Mendelssohn. The Jewish community in Berlin had a proud but troubled history. Levy was also an accomplished keyboard player and, more importantly, a collector of music by J.S. Bach and earlier generations of German composers. Some of her music eventually was donated to Carl Friedrich Zelter and the Sing-Akademie in Berlin. She also commissioned works by C.P.E. Bach, including his late flute quartets (Wq 93–95), and the Concerto for Harpsichord and Fortepiano, Wq 47. (Cypess might have mentioned that autograph scores of these works have been published in facsimile in my own project, as supplements to Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: The Complete Works.)

In spite of the rampant anti-Judaism of Levy’s time, Cypess writes: “Sara Levy navigated this complex social and religious terrain by modestly but seriously staking out her claim in German musical history.”

Perhaps the most enlightening chapter was on Angelica Kauffman, who was born in Switzerland but spent most of her life in Italy. Before settling in Rome, she spent almost 15 years in London, where she was an associate of painter Joshua Reynolds and a founding member of the Royal Academy of Art. In 1794, Kauffman depicted herself as “the Artist Hesitating between the Arts of Music and Painting,” which not only echoes the Choice of Hercules, but also Reynolds’ painting of David Garrick between Tragedy and Comedy, from 1761.

Cypess focuses on two improvvisatrici, Fortunata Sulgher Fantastici and Teresa Bandettini Landucci, both of whom Kauffman painted in Rome. Hester Thrale Piozzi heard one of them at Kauffman’s salons, and wrote in her Observations and Reflections Made in the Course of a Journey through France, Italy, and Germany that the improvised poetry is “sung extemporaneously to some well-known tune, generally one which admits of and requires very long lines; that so alternate rhymes may not be improper, as they give more time to think forward, and gain a moment for composition.” Isn’t this how rappers improvise their lyrics?

Last but not least is Elizabeth Graeme of colonial Philadelphia. In the 1760s and early 1770s, Graeme hosted a mainly literary salon which included two signers of the Declaration of Independence, Benjamin Rush and Francis Hopkinson, the latter a composer in his own right. (Cypess quotes from Benjamin Franklin’s letters, and it is possible Graeme met him in London when she visited in 1764/65, but he was otherwise abroad while her salons took place). Though Graeme’s salons were not focused on music, she was interested in it, collected and wrote her own psalm paraphrases, and featured musical imagery in her poetry.

As Cypess says in her conclusions: “By highlighting the institution of the musical salon, I have shown connections among figures in musical history that might otherwise go unnoticed.” The five case studies in the book provide a fascinating cross-section of the musical salon in the late 18th century, and I highly recommend it for anyone interested in exploring the topic. Perhaps it will even encourage performers to delve further into the musical repertory and make new connections.

Paul Corneilson is managing editor of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: The Complete Works (published by the Packard Humanities Institute, 2005–24), and is now embarking on a critical edition of the operas and dramatic works by Johann Christian Bach.