by Ashley Mulcahy

Published February 16, 2024

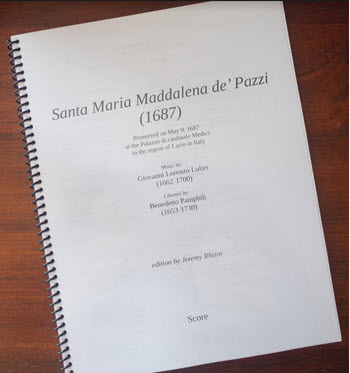

Giovanni Lorenzo Lulier’s 1687 oratorio ‘Santa Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi’ receives its Western Hemisphere premiere

Working for a community ‘that actually cares about religious themes and early music’

Attend a performance by New York’s Academy of Sacred Drama and you’re guaranteed to experience something that you have never heard before. “The Academy is a project dedicated to reviving a forgotten art form,” says Artistic Director Jeremy Rhizor, “something that’s important about what humanity has done.”

While a few beloved Bach and Handel oratorios occupy a prominent position in today’s early-music landscape, the bulk of the genre remains virtually unknown to modern audiences. Rhizor and the Academy of Sacred Drama are systematically trying to change that, one forgotten oratorio at a time.

On February 24 and 25, the Academy performs Santa Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi, from 1687, by the never-famous composer Giovanni Lorenzo Lulier, on the life of a teenage Florentine mystic, Saint Mary Magdalene of Pazzi. In this musical drama, the austere young mystic is called to monastic life but must first overcome every teenager’s greatest obstacle: obtaining permission from reluctant parents. The oratorio has only been performed once in modern times, in 2012 in Oxford, England. These February shows are billed as the “Western Hemisphere premiere.”

The Academy team starts with a blank slate. Most of their oratorios haven’t been performed in hundreds of years, while others are receiving a North American premiere. In either case, the creative team works without a reference point. “This sense of a rich, untapped frontier creates a really exciting atmosphere both for the Academy members and for the performers, almost like discovering something from the past that was thought to be lost to history,” says Kate Bresee, the Academy’s journal editor and box office manager.

But for a small organization with limited resources, giving a 400-year-old oratorio its modern premiere is also a Herculean feat that has required a lot of lifting from a dedicated group of musicians and community members.

Combining his interests in Baroque music and religion, Rhizor, a violinist, organized the Academy’s first performance in May 2013 while still in graduate school. The instrumentalists were a group of fellow students in Juilliard’s Historical Performance program, and the singers were student colleagues from Yale’s Voxtet program. They presented Charpentier’s Mors Saülis et Jonathae at Manhattan’s Corpus Christi Catholic Church (home to the Music Before 1800 series), where Rhizor was also a parishioner.

The Academy still holds an important place in the musical lives of many of these original musicians, like viola da gamba player Arnie Tanimoto. “My ongoing commitment to these projects is driven by two elements: the music itself and the connections I get to make with fellow musicians,” Tanimoto says. “The repertoire is exceptional, providing a thrilling experience for me as a continuo player, especially when contributing to the narrative through accompanying vocal recitative.”

Tanimoto continues, “My collaboration with Jeremy has also played a pivotal role in my commitment to the Academy. Our musical journey and friendship spans well over a decade. This shared history, transitioning from students at Eastman and Juilliard to professional freelancers in New York, has been a constant in both our lives.

“The rapport and shared values we’ve cultivated over the years has made each Academy performance meaningful,” says Tanimoto.

Yet even with a dedicated group of talented musicians, Rhizor’s second oratorio effort failed. As a recent graduate, still couch-surfing in New York City, his circumstances were just too precarious to support a large-scale project. However, the support he received from his Corpus Christi community presented another path forward.

Louise Basbas, former director of music at Corpus Christi and founding director of Music Before 1800, gave Rhizor some of her old scores from the days when MB1800 performed in-house oratorios. Over the next four years, the Academy put on frequent readings of these works at the home of philanthropist Jillian Samant, an early-music enthusiast, in her Manhattan loft. In a day, the young musicians would rehearse just two or three hours for a 90-minute work. Then they’d read through the oratorio for a small invited audience, and wrap up the evening with a potluck. Organizing several of these reading sessions each year proved to be the perfect way for Rhizor to explore a musical corpus that was largely unfamiliar to him.

All the while, Rhizor, who stuck around for coffee hour at Corpus Christi after mass every week, had also been verbally “workshopping” his vision with anyone who would lend him an ear. “I was able to refine the idea over time by talking to my mostly retired friends at Corpus Christi and being able to imagine what this would look like, and what this would look like for them,” Rhizor recalls. In 2017, the project received the financial backing it needed to grow.

“I had been working through in an active way with people who actually cared about religious themes and early music. I created something for them that finally took on some life,” he says.

Oratorio as literary narrative

These days, Rhizor’s horizon is limitless when deciding which oratorio the Academy should present next. With possibilities, however, come challenges. When choosing from a vast body of unknown works, as Rhizor says, “you’re always taking a risk.” When there’s no way to hear a work start to finish, how do you know it will be any good? How do you know if the manuscript will contain errors or other oddities that make pages unplayable?

Over time, Rhizor refined the process of assessing which of the hundreds of neglected oratorios might be worth resurrecting. If a composer is forgotten today, how well were they known in their own time and region? What can we learn about their career (and salary)? Who were the colleagues and patrons? While even the most brilliant composer can write a flop, questions like these guide Rhizor as he clicks through digitized manuscripts.

After he’s decided to revive an oratorio, Rhizor creates an easy-to-read edition and parts for each musician. The tedium and meticulousness of this kind of work cannot be overstated, but Rhizor has his reasons for choosing the long road: “When it comes to learning the music, making the editions has been one of the best parts for me. When you go line by line in excruciatingly slow real time, you get an idea of the piece as a whole that you wouldn’t have otherwise. Every part of it has to be imagined from the ground up. It’s something that has trained me in the way that no other project would have.”

As a violinist who spends hundreds of hours grappling with what’s primarily a vocal genre, Rhizor is certainly an outlier. While the Biblical and religious themes that are central to the oratorio genre play a central role in Rhizor’s own life and identity, Academy founding board member Fred Negem is adamant that, as ticket revenues for Handel’s Messiah and Bach’s St. John Passion demonstrate, one doesn’t have to ascribe to the religiosity that a work might endorse in order to appreciate or even be moved by its artistic and emotional content.

“There are lessons in every story that are immediately applicable to our secular lives,” says Negem. “There are lessons of honor, courage, valor, sacrifice, and every other attribute for which we should strive in our day-to-day lives, but are all too often forgotten. The oratorios exist as literary narratives as well as stories of Biblical histories and lessons.”

Take, for example, the Academy’s 2020 performance of Antonio Gianettini’s La vittima d’amore, which is a poetic telling of the Passion story. As Rhizor tells it, “people who were atheist, Jewish, and Christian, came up to me after the performance with comments like ‘I never understood the emotional story of the Passion.’ These stories are theoretical for most people, but in this experience, you get to see emotionally what’s going on for the characters and to imagine the story in real life.

“Being able to see a story in a performance changes people’s relationship to the story, and that’s what sacred drama can do,” says Rhizor. “It can make that story part of your own story.”

Ashley Mulcahy is a Boston-based mezzo-soprano and graduate of Voxtet Program at the Yale School of Music and Institute of Sacred Music. She sings with numerous ensembles and co-directs her own voice and viol ensemble, Lyracle. For EMA, she recently wrote about the Lisette Project, exploring a Creole song that connects the music, poetry, and turbulent history of Haiti.