Remembrance by Wendy Gillespie.

Remembrance by Wendy Gillespie.

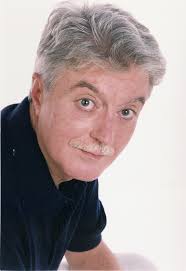

Michael McCraw died on May 30, 2020, six years to the day after being hit by a car and sustaining a traumatic brain injury that forced him into assisted living. He was, on that day, two days away from his retirement from IU, and Michael had lots of exciting plans for the immediate future – recordings, master classes, travel – that were eradicated in the blink of an eye. The driver has not been found.

Michael enjoyed an intimate relationship with music for more than sixty years, sharing that relationship with students at the Jacobs School of Music for seventeen of those years. Internationally known as a virtuoso on the baroque bassoon, with some 140 recordings in his discography, Michael is mentioned in the standard reference work on classical music as a notable performer and teacher of our time. However, his impressive professional credentials do not even begin to capture the essence of Michael McCraw. For that, one must also take into account the outgoing, larger than life personality and convivial life style that render him unforgettable to musicians everywhere, not to mention publicans, servers, and restaurateurs from Bloomington to Barcelona, Charleston to Cologne, and Toronto to Turin.

Reginald Michael McCraw was born on October 19,1948 to a fiddler and banjo picker in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Michael learned to read music at the age of five singing shape note hymns in a rural church. In his childhood, he had piano lessons, then took up the clarinet and in his senior year of high school, Michael began to play the bassoon. After starting a music education degree in college, Michael realized that he wanted to pursue performance seriously, so he transferred to the recently opened North Carolina School of the Arts. He went to New York City after he graduated to pursue further studies and quickly became an active freelance musician. It was there, in the heady days of the early 1970s, that Michael and I became friends, undertaking exploits that would be completely inappropriate to recount on this occasion.

By 1973, Michael had become interested in early repertory and taken up the baroque bassoon. There were no teachers for that instrument at the time, so he taught himself to play and make reeds for it, reading treatises and letting the instrument teach him how it wanted to be played. He went to Cologne in 1979 as an experiment and ended up staying in Europe until 1991, building a busy career performing and recording with most of the leading early music ensembles of the time.

Michael’s next move was to Toronto to become principal bassoonist with the very successful period instrument ensemble Tafelmusik, where he remained until 2001, when the visiting lecturer position he had held at the Jacobs School of Music since 1998 evolved into a full time, tenured position. Many of his students have achieved notable success in performing and teaching careers, and Michael’s move to Bloomington brought him back into the lives of many musicians whom he had known and worked with in Europe and earlier in New York City.

In addition to being a singular musician and teacher, Michael McCraw was also a singular human being. He remained a country boy despite his international career, and he loved sitting on the porch of his house drinking and smoking with friends. Michael the bon vivant and raconteur extraordinaire really knew how to throw both a dinner for two and a reception for 50. An avid and creative cook, his interest in food inspired him to undertake a recipe book whose working title was White Trash Visits Italy, by Termey-Sue Bassano. He was well known as a patron of all the finer eating and drinking establishments in Bloomington. Michael had an avid interest in the visual arts, some of which also interest the Kinsey Institute. (But he didn’t like Andy Warhol, because Andy once spiked his drink behind his back at a party, leaving Michael feeling terrible the next day.) His penchant for delighting the eye extended to a sartorial splendor that turned heads, even at a school replete with opera divas. Michael chose not to drive, and his was a very familiar face to Bloomington bus drivers, but he was also known to walk up to complete strangers in cars and very politely, always the Southern gentleman, ask them for a ride. Nobody ever refused.