The admired a cappella ensemble bids the world farewell after three decades of radiant artistry.

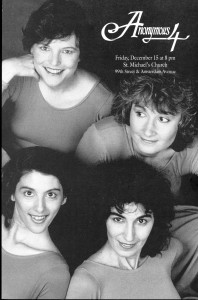

Sunday morning, August 3, 1986. The Upper West Side of Manhattan had been deserted by anyone who could get away, and not many showed up on West 99th Street at St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, where four of us—two choir members and two friends—had agreed to sing the service that day. We loved the medieval music we’d been reading together for a few months. But we wondered what the congregation, hearing the debut of soon-to-be Anonymous 4, would think of the strange old sounds.

Afterward, enough of the few churchgoers were pleased and fascinated (or said they were) to encourage us. But it was not their reaction that fueled our launch: it was our own pleasure in the musical process—finding, voicing, and interpreting songs and plainchant that few others around us bothered with.

Our first concert program—Legends of St. Nicholas—was quickly scheduled for the following December, again at the Tiffany-windowed, acoustically perfect St. Michael’s. We sang in the side chapel so our enthusiastic audience of fifteen friends and family did not seem quite as sparse at it was. If drawing a big crowd to hear our new musical idea had been the criterion for continuing, it would have been over as soon as it began. But it wasn’t, and so it wasn’t.

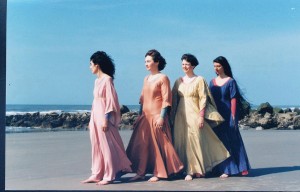

We rehearsed long and often, for few prospects and little money. Within a year, we lost a member to

our grueling-for-nothing schedule, but we were soon four again when Ruth Cunningham joined Marsha Genesky, Johanna Maria Rose, and me.

Beginning in 1987, St. Michael’s offered us a residency and a concert series, and there we steadily built repertoire and refined our own style of programming: compact, thematically unified, appearing quietly out of some distant place, and disappearing back there again. When our listeners reported, over and over, that our concerts had “transported” them, we knew why we were spending so much time in the library and in rehearsal.

The Anonymous 4 style of programming was no accident—or perhaps, in a way, it was: each of us brought along skills and experiences that seemed to interlock and work together in an almost magical way.

Johanna had studied acting before earning a master’s degree in early-music performance from Sarah

Lawrence College, which offered one of the first such programs in the United States. She and Marsha—who had fallen in love with singing early music in Mary Anne Ballard’s Collegium Musicum at the University of Pennsylvania—both had deep experience with literature and languages, as well as music. A storytelling approach to program building was the natural result. It quickly became our method and remained so.

Ruth had been playing and singing early music since age 12 and went to New England Conservatory to study early-music performance. I had sung chant from square notation as a child (before seeing a single round note), studied Latin for several years, and specialized in medieval music history in graduate school.

Shaping Phrases and Programs

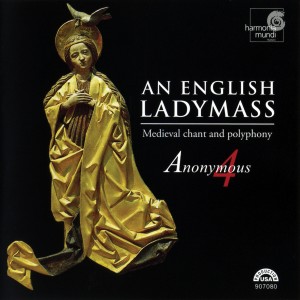

The tools were there, and we used them. Each program had a single focus: a saint (Legends of St. Nicholas, Miracles of Sant’Iago), a liturgy (An English Ladymass), a feast (On Yoolis Night), or a manuscript (The Montpellier Codex for Love’s Illusion). Each was pulled along by a narrative thread, and each was developed, owned, and treasured equally by us all.

From the beginning, we wanted our programs to include plenty of plainchant, without which the polyphony could not sound as miraculous as it had 700 years ago. Plainchant demanded much of our attention, and this work is where our “unity of intent” (sometimes called our “blend”) originates: not from manipulating or matching our sounds, but from all agreeing—not always without a fight—on the shape and purpose of every single phrase.

Our different way of programming and performing began to get some notice. We received our first review in 1987, thanks to Wendy Powers and the New York Recorder Guild. John Schaefer, the new-music guru of WNYC, New York City’s public radio station, heard about our programs—“so old that they’re new,” he said—and began to feature us. Without the constant support of public radio and early believers like John and Robert Aubry Davis of WETA in Washington, D.C. (now of Sirius XM), it would have been much harder for our early career to gain traction.

When the esteemed music critic Andrew Porter wrote a lovely piece in The New Yorker about our 1989 Christmas concert at St. Michael’s, we were stunned: we hadn’t even known he was there. Now that we had a high-visibility rave, the Genensky-Rose booking and publicity agency began working to get us out-of-town concerts. We got as far as South Carolina, Florida, and New Orleans, and have since visited every state—except South Dakota—and several dozen countries.

All of this spurred us on to explore more repertoire and continue our intense research and rehearsal schedule. But now our concert booking efforts were starting to land some bigger prizes.

The prize of fondest memory came in 1990 at Tage Alter Musik Regensburg, the festival in the medieval German city. The presenter had selected the venue—the13th-century Dominikan erkirche—especially to match our English Ladymass program and hoped it would do. We just nodded our heads and tried not to appear unprofessionally giddy at the prospect of singing a medieval concert in an actual medieval church for the first time.

For the Record

After hearing our performance, a fellow artist at the festival said he thought it was time we made a recording. The seed was planted, and our first recording project began.

Our demo cassette reached the desk of harmonia mundi usa vice president and artistic director Robina

G. Young in Los Angeles. She listened to it and called us up. We met for lunch at a Japanese restaurant on Columbus Avenue. And we signed a one-off deal, in 1991, to record An English Ladymass. It sounds so simple now, but we knew many demo cassettes were aimed at that desk (and at others like it). We felt almost too lucky—but then thought about all those rehearsals.

We recorded An English Ladymass at Skywalker Ranch in Marin County, California. The session went well, and we were invited to record a Christmas program. While On Yoolis Night was being edited in early 1994, An English Ladymass began to creep up the classical chart. It rose to the top ten, staying there for many months. Around that time, we signed with Herbert Barrett Management and, in the fall of 1994, started touring full-time.

Although our recordings received good notices from early reviewers, including Jerome F. Weber in

Fanfare, and sold well, one reviewer consistently criticized us for distorting medieval “men’s music.” But we had been championed early on by musicologists like Ernest Sanders (who had edited much of the English Ladymass polyphony) and Alejandro Planchart (who later transcribed the polyphony for our 1000: A Mass for the End of Time), so we enjoyed those diatribes and carried on as usual.

With a busy touring and recording schedule, we now worked twice as hard at developing new programs.

We explored medieval repertoires and ideas as quickly as we could think of them: French, Spanish, and

Hungarian programs, and the music of Hildegard of Bingen (11,000 Virgins). Our audiences continued to tell us that they had been “transported” or, most memorably in a medieval chapel in France, that “the stones remember this music.”

In 1994, New York composer Richard Einhorn asked us to be part of his oratorio Voices of Light, written

to accompany Carl Dreyer’s 1928 silent film, The Passion of Joan of Arc. He said he had hesitated to invite us, thinking that the very medieval Anonymous 4 wouldn’t consider music by a living composer. But after hearing just a few moments of his MIDI demo, we immediately agreed to take part in this modern masterpiece—and are grateful to this day that we did.

In 1998, Corpus Christi Church, near Columbia University, became our new home, where we kept our office, rehearsed, and appeared regularly on the Music Before 1800 concert series, led by our friend and angel, Louise Basbas.

That same year, Ruth, following her longtime passion, left the group to train and work as a sound healer. We held auditions to replace the irreplaceable, and chose Jacqueline Horner-Kwiatek, a new-music specialist from Northern Ireland, who had won a green card and recently moved to New York. She walked right into European and American tours with six different programs, assuming she had to memorize them all. We will always treasure the look on Jacqui’s face when we told her that they did not, in fact, have to be sung from memory.

We soon began to commission more contemporary music, from Peter Maxwell Davies (for Wolcum Yule, with virtuoso harpist Andrew Lawrence-King), Steve Reich (for Know What Is Above You), and John Tavener (for Darkness into Light, with the Chilingirian Quartet).

And we continued to develop medieval programs, touring and recording without a break. On September 11, 2001, we were recording la bele marie—13th-century conductus and chansons (a program inspired by the great musicologist Rebecca Baltzer)—at the Christian Brothers monastery in Napa, California. We wanted desperately to go home to our loved ones in New York, but flights were grounded, so we kept on recording, our heavy hearts comforted a little by our fellowship and the heavenly songs.

En Route to a Finale

By 2002, we began to feel that it was time for a break—and probably time for each of us to pursue other goals. As we contemplated our final moves, we still had two recordings to complete. One seemed inevitable: a second recording of the music of Hildegard of Bingen (The Origin of Fire). And one did not. But a title had recently popped into my head as I listened to some early-American shape-note tunes on the radio—American Angels.

I had taken charge of musical research for the medieval programs and Johanna had done the same for the more eclectic Wolcum Yule. But Americana? Considering Marsha’s advanced degree in folklore and her teen years spent as Santa Monica’s answer to Joan Baez, it was now her turn.

We listened to field recordings, read stacks of shape-note tunes and gospel songs, agonized over musical and linguistic inflections. And that was the easy part. Then we had to sell this concept to our management and recording company, which we did.

American Angels appeared in 2004 as our last recording and touring program.

To everyone’s surprise, it became a No. 1 hit on the classical chart and sat there for a long time. Although we had folded our tent and parted as friends, the gesture of trust harmonia mundi had made in letting us record this program had, by rights, to be repaid. The record company asked for a second Americana program, and we created Gloryland (2006), with new-grass stars Darol Anger on fiddle and Mike Marshall on mandolin.

In 2007, Johanna left the group to follow other pursuits. Just then, Alliance Artist Management (spun off from Barrett Management) passed along an invitation to perform at the Edinburgh International Festival, something we had long hoped to do. Ruth returned, the natural choice to make us four one more time. We created an Anglo-American Christmas program, The Cherry Tree, to tour and record, and agreed to do three more recordings for harmonia mundi.

One more major contemporary project came our way. In 2011, we commissioned a short work from

Bang-on-a-Can composer David Lang for our 25th-anniversary “Anthology” touring program. The result was so mutually pleasing that it grew into the staged, full-length show, love fail, premiered in 2013.

In the spring of 2014, we decided to close up shop at the end of 2015. But there was one more harmonia mundi recording to make. We chose to mark the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War with 1865, an album of popular songs “in the air” that year. We were joined by multi-instrumentalist and singer Bruce Molsky, a traditional music star with a sense of adventure.

The 1865 recording session in June 2014 was our last—the first of many lasts. After that, almost every

concert tour stop was the last time we would visit that place and sing for those people. Presenters and audience members were aware as well and greeted us with memories and stories of concerts long ago. It has been a fabulous run, with so many surprises, and so many gifts. Best of all, we were able to keep re-creating our original vision of making each program together, ourselves. Although the work never stopped, it never really seemed like work.

Maybe that’s why it all went by so fast.

Anonymous 4: The Name

It was the fall of 1986, and we were about to start publicizing our first concert performance, Legends of St. Nicholas. We suddenly realized that we would need an ensemble name to put on the posters and press announcements. We tossed ideas around.

The medievalists I had studied with—Raymond Erickson at Queens College and Ernest Sanders at Columbia University—each spent many hours of their class time (and my library time) on one particular 13th-century treatise. The fourth of the anonymous treatises in Edmond de Coussemaker’s Scriptorum de musica medii aevi (“Anonymous 4” for short) not only detailed the origins of rhythmic notation, but also connected composers’ names with well-known pieces.

Having had two thorough drenchings in this very important document, I naturally suggested, half

seriously, “Hey, how about Anonymous 4?”

Unanimous agreement was not forthcoming, but when it was time to make the poster, neither was a better name. And once we’d paid an artist $150 to create our original logo, it was way too late to turn back.

Sorry, dear professors.

—Susan Hellauer

The Power of Music

Not long after Anonymous 4’s first recording was released, audience members began to tell us about how they used our music.

Some people found that putting on our CDs at the end of the day helped them relax. For others, listening to our recordings became a beloved part of their spiritual life and practice. A number

of people told us moving stories of having played our recordings when a loved one was dying: the music created a beautiful, sacred space that helped both the dying person and those with them. Several women with whom we spoke had even given birth to the sounds of Anonymous 4’s music.

These stories of listeners using our music for spiritual and healing purposes were part of the

inspiration for my leaving Anonymous 4 in 1998 to study music and healing, and to become a sound-healing practitioner.

I was happy to have the opportunity to return to the group in 2007. After concerts, people still come to us with tears in their eyes to tell us how much our music means to them. I am glad and humbled at how the music we have sung with such care and attention over the years has so deeply touched the hearts of so many.

—Ruth Cunningham

Americana

We were sitting in a restaurant somewhere in Germany when Susan announced that the title American Angels had come to her in a vision. She had heard some tunes by the 18th-century American composer William Billings on the radio, and the harmonies sounded kind of medieval to her.

But, Susan said, she didn’t know anything about American music, so she was handing this project over to me.

Unlike the other members of Anonymous 4, I had found my first musical home in Anglo-American roots music. I loved old ballads, shape-note tunes, and the tight, close harmony of bluegrass vocals. It was in Mary Anne Ballard’s Collegium Musicum at the University of Pennsylvania, where I was doing graduate work in folklore, that I had my first singing encounter with a three-part medieval piece. The close voicing and the preference for open fourths and fifths sounded kind of American to me.

Doing the research for American Angels brought me full circle to my first musical love. Best moment: “Angel Band” making the cut for the show. My previous “performances” of this 1860s gospel song had taken place in a closet (with a certain folklorist friend who was too shy to sing with me in an actual room!)

—Marsha Genensky

How do you say that?

One of the joys of singing in dead languages is that no one can really say you’re doing it wrong. Even so, hunting down and comparing the existing research about how to pronounce these ancient languages was a necessity. One of the first we delved into deeply was Middle English. Much of our repertoire was in Latin, but pronounced as influenced by the country and region where it originated. We also sang in Old French, medieval Italian, ancient Coptic, and a number of living languages.

The requirement in diction classes at Manhattan School of Music to become fluent in International Phonetic Alphabet turned out to be a great advantage when dealing with unfamiliar phonemes.

When the book Singing Early Music came along in 1996, we became beta testers. Even before its publication, [editor and scholar] David Klausner had been immensely helpful as one of the medievalists we often consulted about pronunciation.

An important lesson we learned about the confluence of words and music came from a French 13th-century conductus—fast-moving and set syllabically (one syllable per note). Before we applied our French Latin choices, this particular piece felt like trying to sing through mouthfuls of pebbles. The minute we softened the Latin with its French influence, the piece was magically transformed into a flowing brook.

—Johanna Maria Rose

The Force was with us

As Anonymous 4’s new-music girl—my outside activities are almost entirely in the field of new works—it was my pleasure to help facilitate commissions with some of the world’s leading composers, including Peter Maxwell Davies, Steve Reich, John Tavener, and David Lang.

However, I must confess that one of the most memorable experiences I had with Anonymous 4 was the pleasure of recording several of our CDs at Skywalker Ranch, owned by George Lucas of Star Wars fame. I am unashamedly a huge Star Wars fan, so being on the ranch, seeing props from the movies, and, on one momentous occasion, seeing Lucas himself having lunch in the cafeteria, were thrilling. Oh, and we recorded some pretty good CDs in the fantastic Skywalker Sound facility, including American Angels and Gloryland.

It was so much fun for us all to go to the on-site gift shop to buy T-shirts, coffee mugs, and other memorabilia for ourselves and loved ones—a welcome reward after a long recording session and a chance to collect souvenirs of a special time that I treasure to this day.

—Jacqueline Horner-Kwiatek