It was hidden for more than a century in the basement of an old house. The instrument’s discovery offers important hints about a forgotten history of New England ensemble string playing.

Last summer, a man living near Detroit contacted me about a mysterious stringed instrument. He had found it wedged between the basement joists of his mid-19th-century house and, remarkably, had noticed the instrument only after having lived there for decades. When he gently brought it down from its perch, he found it covered in dust and grime and that it had likely been untouched since the early 20th century, when renovations by a previous owner concealed it from view.

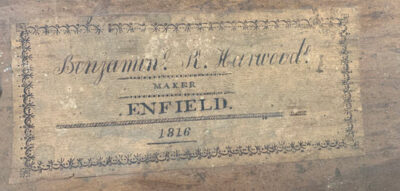

Laid on his kitchen table, where I first saw it, the instrument was about the size of a tenor viola da gamba but closer in shape to a violin or cello. The hand-written label read “Benjamin R. Harwood, maker Enfield 1816.”

I soon discovered that the Enfield on the label referred to one of several flooded towns now at the bottom of the Quabbin Reservoir in western Massachusetts — the area, by coincidence, where I grew up. (How it got to Michigan is unknown.) The weird coincidences continued: My mother now lives just off Enfield Road, a winding country lane that dips down toward the reservoir and disappears beneath the water just a couple of miles away from the inundated town where the instrument had been built.

I soon discovered that the Enfield on the label referred to one of several flooded towns now at the bottom of the Quabbin Reservoir in western Massachusetts — the area, by coincidence, where I grew up. (How it got to Michigan is unknown.) The weird coincidences continued: My mother now lives just off Enfield Road, a winding country lane that dips down toward the reservoir and disappears beneath the water just a couple of miles away from the inundated town where the instrument had been built.

But what was this instrument? It resembled the larger (and more common) New England stringed instruments that appeared around 1800 as, supposedly, accessories to congregational singing, but it was too small to be a so-called church bass. And it was too big to be played on the shoulder, like a violin or fiddle. It was clearly a tenor instrument, and its discovery contributed important hints about a forgotten history of New England ensemble string playing that I had been researching for over a decade.

New England viols were built and played in the decades following American independence. Ensembles of viols (bass, tenor, and alto) — sometimes joined by a flute, clarinet, or fiddle — were used in all manner of New England community music-making, from accompanying dances to intimate domestic gatherings to leading psalmody inside and outside the meetinghouse.

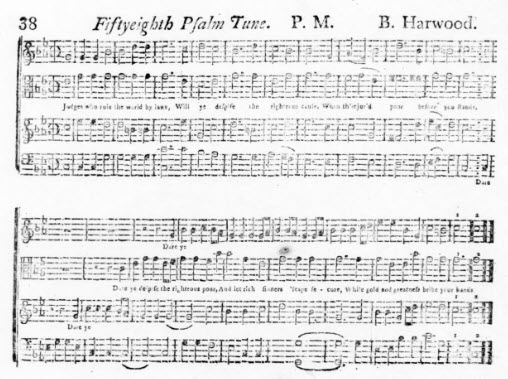

It was the efflorescence of “Yankee” psalmody, in fact, that created the initial demand for New England viols, instruments designed and built by local artisans with little or no access to European models. Following various religious awakenings during the 18th century, New England-born composers and music teachers would publish and print well over seven thousand compositions between about 1770 and 1811. These comprise (mostly) 3- and 4-part hymns and anthems in a rough-and-ready musical language that emphasized singability by congregation members and an open, forthright harmony that resonated in plain, wooden meetinghouses across New England and, eventually, territories to the south and west.

After more than a century of Puritan proscriptions against all but the most simple and austere church music, it would take a couple of generations for New England congregations to re-learn how to sing in parts from notation. And suspicion about the suitability of musical instruments in worship lingered in many places long after communities had accepted this so-called “regular singing.” Often, skirmishes about whether instruments belonged in a sacred service played out around the prospect of acquiring a “bass viol” to support a fledgling group of volunteer congregational singers.

Indispensable tool of the singing master

The proliferation of bass viols — we’ll unpack this term in a moment — in New England congregations seems to have followed on the heels of the emergence of the “singing school” as a widespread cultural phenomenon that reached even the most remote and rural New England communities by the turn of the 19th century. Singing schools typically unfolded over an intensive week or were held weekly for several months. Locals — usually youth old enough to read but not yet married — would gather in the meetinghouse or other public place to be taught by an itinerant singing teacher, who would introduce students to musical notation and the musicianship skills necessary to sing the 3- and 4-part “folk” polyphony that was published in the astonishing quantities described above.

In one of the numerous surviving accounts of the singing school phenomenon, Moses Cheney recounts attending his first singing school in rural New Hampshire in 1788. Cheney writes: “…and it came to pass when I was about twelve years of age, that a singing school was got up about two miles from my father’s house. In much fear and trembling I went with the rest of the boys in our town. I was told on the way to the first school that the master would try every voice alone to see if it was good. The thought of having my voice tried in that way, by a singing master too, brought a heavy damp on my spirits. I said nothing, but traveled on to the place to see what a singing school might be.” (Alas, we never find out what happened when he got there.)

In many cases, itinerant singing school “masters” were also the composers and compilers of the hundreds of oblong tune books that proliferated, starting in the final decades of the 18th century. Masters would often travel with stocks of their printed books to sell to students during singing schools and were famously resourceful for cobbling together a living of which musical activities were only a part. Washington Irving’s character Ichabod Crane (who would be pursued through the foggy woods by the terrifying Headless Horseman), for example, provides an informative caricature of the Yankee singing master. Irving writes “In addition to his other vocations, he was the singing master of the neighborhood, and picked up many bright shillings by instructing the young folks in psalmody.” Such resourcefulness is likely linked to the widespread adoption by the 1790s of rustic, cello-like instruments to support the music-making in singing schools (and soon meetinghouses). As anyone who has worked with inexperienced singers knows, a confident and in-tune bassline can be extremely helpful in keeping an unruly group of singers together and in tune.

The earliest New England bass viols — one dated 1788 by Benjamin Crehore of Milton, Mass. is the earliest extant dated instrument — were probably built by singing masters themselves or by local carpenters or woodworkers contracted by the masters. More certain is that the New England bass viol became an indispensable tool of the singing master, and that its use in the singing-school milieu was likely responsible for its proliferation and widespread use in (and outside) New England meetinghouses a couple of decades later. This close association with psalmody may be the origin, incidentally, of the confusing 20th-century coinage “church bass” to describe New England bass viols. Surviving instrument labels, literary references, and other sources almost invariably use “viol,” often preceded by “bass” or “tenor.”

Thus, by the early decades of the 19th century, the singing-school phenomenon had passed its peak but had left an indelible mark on New England congregational music making, from the thousands of polyphonic tunes in hundreds of published tune books, to choirs of community members possessing some degree of music literacy and deeply committed to singing polyphonic Yankee hymnody, to the ubiquity of locally built stringed instruments to supplement and support the singing.

But it wasn’t just bass viols, it turns out, that these New England artisans made, and it wasn’t just bass viols that were used to accompany the singing of New England psalmody. In fact, instruments referred to variously as “tenor viols,” “alto viols,” and “small viols” appear in many surviving discussions of New England musical culture during the first half of the 19th century.

The diary of William Bentley, pastor of Salem’s East Church, for example, contains numerous entries describing the use of what he refers to as a “tenor viol” in his community. In November 1797, Bentley writes, “In all our societies the Bass viol has been used, having been introduced about two years since. A Violin & Clarionet followed in our worship. The number of these, with the Tenour viol, formed our Band on this solemnity. The order of service was, an air (Hymn 73, the instruments going over the tune, before the vocal music joined) …”

In another example, in the June 3, 1827 edition of the Boston newspaper The Morning Star and City Watchman, Elias Smith disapprovingly writes, “On the first day of the week, the minister says ‘Let us praise God, or worship him by singing an hymn’; which he first reads over. Instead of hearing songs from the redeemed; the first sound which strikes my ear, is from the bass viol in the gallery, with the tenor viol, flute, clarionet, and perhaps bassoon… Once a year, the singers and players on instruments must go to Deer Island to have a Chowder and Dance. The same worshippers, the same instruments, or some of them go, and the instruments, and those who use them, answer in the worship, or dance. Does this look like New Testament worship?”

Could the rediscovered instrument from Enfield be a tenor viol like those mentioned by Bentley and Smith?

‘A rich and diverse musical culture’

During the 18th century, “tenor viol” was the standard term in the English-speaking world for what we now call the viola, in the same way that bass viol was used to identify the instrument we now refer to as the violoncello or cello. To add to the confusion, modern readers associate the word viol with the viola da gamba, which is certainly not what New England writers meant when they used the terms bass viol or tenor viol. If all that survived from early republic New England were these confusing written terms, we might conclude that the passages above simply refer to cellos (“bass viols”) and violas (“tenor viols”), but a wealth of surviving instruments — including the Enfield tenor — tells a very different story.

In his 2002 article “Early Violin Making in New England,” Darcy Kuronen, former curator of the musical instruments at the Boston Museum of Fine Art and the leading expert on New England instruments, writes, “A handful of surviving instruments have bodies much smaller than a bass viol, but considerably longer and thicker than a viola…[T]heir large bodies (between 19 and 21 inches long, with ribs nearly 2 1/2 inches high) dictat[e] that they be held upright between the legs, rather than at the shoulder like violas (which are often closer to 15 inches long with ribs only 1 3/8 inches high).”

Kuronen continues by noting that the production of regular-size violas in New England was “very limited before the second half of the nineteenth century.” Kuronen would know — in the Boston MFA’s instrument collection are several such tenor viols. Frederick Selch, a researcher whose collection of dozens of New England stringed instruments now resides at Oberlin Conservatory, estimated that he had examined more than twenty surviving “small viols.”

And my work collecting, identifying, and restoring New England viols (with help from grants from the Viola da Gamba Society of America) over the last decade has added another five instruments to the list of known surviving New England tenor and alto viols. My collection of instruments includes a tenor from Abraham Prescott’s first shop in Deerfield, NH, the tenor-sized instrument from Enfield, Mass., an unlabeled tenor-sized instrument possibly from the Hudson Valley, and tenor and alto viols from the shop of Myron Kidder (Northampton, Mass.).

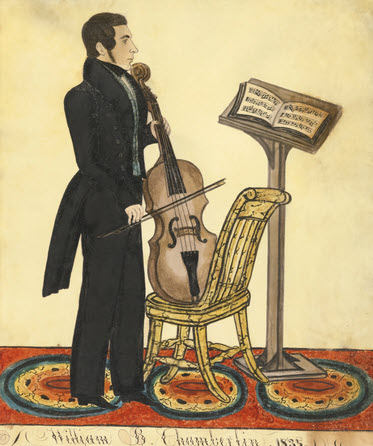

While the majority of surviving small viols are “in captivity” in museum collections and in no condition to be played, three of my instruments have been restored to playing condition and the other two are undergoing restoration. Taken together, these surviving New England viols demonstrate that the term “tenor viol” as it appears in the contemporaneous accounts like those by Bentley and Smith, above, likely does not refer to the standard viola, but to instruments smaller than New England bass viols that are large enough to be only playable “down,” held on the calves like a viola da gamba or on a chair, as is pictured in the 1835 portrait of William Chamberlain by itinerant New England painter Joseph H. Davis (active 1832–1837).

Most surviving New England viols superficially resemble familiar European stringed instruments in their shape and number of strings (typically 4, though numerous 3- and 5-stringed instruments survive), although a closer look reveals that New England viols don’t fit comfortably into either the “braccia” (arm) or “gamba” (leg) categories typically applied to European bowed strings. There is no evidence of standard sizes or string lengths, for example, and the lengths of necks in relation to bodies vary from instrument to instrument.

Some New England viols sport scrolls that look somewhat like their European counterparts, yet there are many surviving instruments with more (or fewer) turns, with radically different proportions, or with scrolls of a different shape altogether. When New England instruments are opened on the restorer’s bench, it becomes clear that very few, if any, makers had access to European-made instruments as models, let alone the specific tools and techniques that had been developed over centuries in Europe.

Rather, New England viols show an incredible diversity of ingenious, idiosyncratic solutions to familiar challenges, like attaching ribs to tops and backs, stabilizing tops against the downward pressure on the bridge, and providing a way for players to tune their open strings. (Prescott’s account book shows that he traded raw brass and bushels of grain to the local clockmaker to cut the mechanical tuners characteristic of his instruments.) Surviving fingerboards reveal a multiplicity of inlays or markings to help orient the player, and the occasional use of tied or inlaid frets cannot be ruled out, though normal practice appears to have been fretless.

New England viols show an incredible diversity of ingenious, idiosyncratic solutions to familiar challenges

Surviving fragments of strings show a similar diversity of solutions, from raw cow gut twisted into thick bass strings to farmer’s twine to overwound strings imported from England or Italy. While we know of several shops that turned out dozens or hundreds of instruments, many New England viols were built by local craftsman using local materials and a general expertise working with wood. Surviving bows, of which there are few, appear to have similarly been constructed as practical tools using local techniques and materials.

One of the instruments mentioned above that I restored, a “Hudson Valley” tenor, resembles nothing more than stylized illustrations of stringed instruments that appear in early 19th-century prints. Is it possible that the distinctive shape of this instrument is due to a rural artisan having relied on such illustration in lieu of more definitive experience with stringed instruments or construction techniques?

To imagine the diversity of music making involving New England viols that occurred in the decades following the American Revolution, it’s worth returning to Bentley’s and Smith’s quotes, above. First, both writers describe consorts composed of two or three stringed instruments (bass viol, tenor viol, and violin) mixed with winds (flute, “clarionet,” and bassoon). These descriptions accord with dozens of surviving prints and manuscripts from New England containing sacred and secular music for small ensembles of viols and winds, such as Samuel Holyoke’s Instrumental Assistant, Vol. I (1800) or Joseph Herrick’s Instrumental Preceptor (1807), or any of the innumerous manuscript collections from the period.

Strikingly, both Bentley and Smith describe viol playing that is independent of singing—Bentley describes how the instruments would “go over the tune, before the vocal music joined” while Smith decries the use of instruments from the meetinghouse being taken to accompany dancing and feasting (“chowder”!).

When the substantial surviving repertoire of fiddle tunes from England, Scotland, and Ireland—many transmitted with basslines and sometimes additional voices—is added to the enormous repertoire of psalmody described above, a rich and diverse musical culture is revealed.

Archival evidence testifies that ensembles (“consorts”?) of New England viols accompanied singing, both in and outside the meetinghouse, played instrumental polyphony based on dance and psalm tunes and sometimes, perhaps, earlier European models. (I recently discovered, for example, unknown settings of variations on “Greensleeves” and “la Folia” in two manuscripts from Connecticut dating to 1798 and 1803.)

New England artisans, like Enfield’s Benjamin Harwood in 1816, crafted viols and other instruments with limited (if any) knowledge of European methods, tools, or models, and residents of rural New England communities cultivated music for worship, dancing, and enjoyment with little concern, evidently, with how closely their homespun musical culture resembled the practices of their ancestors across the ocean.

Loren Ludwig is a viol player and music researcher based in Baltimore. He holds a B.Mus. from Oberlin Conservatory and a PhD in musicology from the University of Virginia. His blog, describing the origin and ongoing restoration of this instrument, is available at https://lorenludwig.com/current-projects/harwood-tenor-viol-restoration/