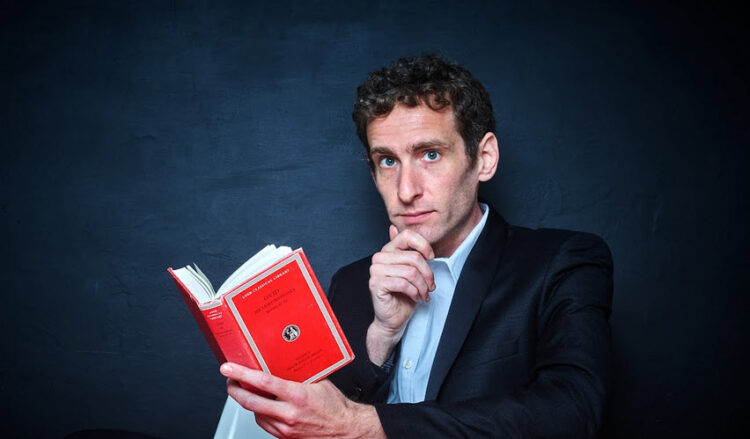

As a composer, teacher, and America’s leading Baroque bassist, Doug Balliett is devoted to radically authentic music-making

Balliett ‘approaches a bass line with maximum funk’

On Trinity Sunday this past June, the musicians at Manhattan’s St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church spread themselves strategically throughout the sanctuary. A soprano stood in the musicians’ usual corner, next to the organ console. On the opposite side of the room, a mezzo-soprano sat beside a single-manual harpsichord. And at the sanctuary’s rear balcony, a baritone stationed himself by a charmingly janky upright piano. The three voice-keyboard duos, along with the central altar table, formed a tenuous cross shape

Presiding from the organ was Doug Balliett, the composer who has been in residence at St. Mary’s since the fall of 2020. Each week, Balliett writes new liturgical settings for his house band, Theotokos (“Mother of God,” in Greek), a rotating array of New York City’s freelance vocalists and early-music specialists. For Trinity Sunday, I served as the ensemble’s guest baritone. (Call it journalistic privilege.)

That service was my first time hearing Balliett play the organ; he’s best known as America’s most in-demand Baroque bassist. He’s an essential fixture of ensembles that make the New York Baroque scene a hotbed of exploration and experimentation — rather than a stentorian monument to the past. As Juilliard’s professor of Baroque bass, he’s galvanizing the next generation of historical performers with that same forward-thinking energy.

But Balliett is a composer in equal measure, and his works blur lines among a dizzying number of genres. His singular voice has attracted praise not only from his local circles of fellow adventurers, but from organizations farther afield.

For the last few years, Balliett has largely laid his busy gig schedule aside for the life of a modern-day Kapellmeister — a Bach of the Bowery. At St. Mary’s, he leads four Masses a week in three languages. Like many musical directors past and present, Balliett is a comprehensive talent: In any given service, he’ll float from bass to organ, viol to guitar, often stopping to sing a line or two in his gravelly, folksy baritone. And whether it’s in his own compositions, Gregorian chant, or Spanish-language praise songs, when someone hits a money note, his grin is wide and toothy.

The St. Mary’s gig was Balliett’s first plunge into ecclesiastical life. He grew up an occasional churchgoer, he told me over coffee in an airy St. Mary’s loft, but for his debut season on the job, he was flying solely from what he’d gleaned through music history courses and church-adjacent freelancing.

After three years, he’s mastered the peculiar ins and outs of Catholic procedure. How to match Old Testament passages with gospel readings. What texts to set and when. How the never-ending cycle of saints makes every day a holiday. For the latest year of his residency, he’s even moved into the two-room apartment at the top of St. Mary’s tower, awaking with the churchyard roosters’ crowing and joining the clergy to chant psalms through bleary eyes at 7:15 a.m. morning prayer.

When Balliett started at St. Mary’s, his compositional career already had many conventional marks of success — major premieres, raves from The New York Times, and a two-hour opera on an Arthurian tale, Gawain and the Green Knight, that the composer says changed his life. “It was the first piece of that size that I really completed,” Balliett recalls with humility. “When I finished it, I had this insane feeling: If I can do that, there’s so much I can do.”

Completing his opera, in fits and starts over two years, gave Balliett an electrifying rush of ambition. But his post at St. Mary’s has fundamentally transformed his creative process: The newfound pressure of weekly deadlines stripped him of the luxury of time, to which he’d grown accustomed.

“You can’t wait for inspiration. Ever,” Balliett says of the Kapellmeister’s schedule. “You just have to go.”

He rarely begins composing until the previous week’s services are over, and after three years of six-day sprints — Theotokos rehearses on Saturday evenings — Balliett is never lost for a starting point. “I don’t feel that tyranny of the blank page anymore,” he says. “It’s like diving into cold water. If you never leave the water, you’re never cold.”

With his residency, Balliett almost feels as if he’s stepping into the shoes of Bach or Telemann. He likens his strict compositional regimen to LARPing, or live-action role-playing, a favorite pastime of fantasy-obsessed teenagers the world over. For Balliett, the routine both clarifies and mystifies the accomplishments of those prolific Kapellmeisters that came before him. “You realize it is possible to produce a certain volume of music each week,” says Balliett.

Hip-hop Baroque

Balliett’s composer life started around fifth grade. As a young bassist in Boston, he and his identical twin brother, Brad (a bassoonist), both viewed composition as a natural part of learning their instruments — a very Baroque approach. But Balliett claims it was only in 2001, once he landed at Harvard for his undergraduate degree, that he began to compose pieces which, as he puts it, “didn’t suck” — mostly incidental music for campus Shakespeare productions.

Balliett spent much of his musical time at Harvard in the practice room, drilling orchestral excerpts with hopes of securing a tenured symphony job. Those four grueling hours of daily practice paid dividends. After junior year, he left Harvard to assume the assistant principal bass seat with the San Antonio Symphony.

“I discovered very quickly that orchestra life is great, but it’s just not for me,” Balliett says. He wasn’t finding his fulfillment onstage, but rather at the pop-up house concerts he would mount with his friends. “And meanwhile, my twin brother had moved to New York City — he was meeting Meryl Streep backstage after concerts!”

Eventually, the fear of missing out became too much to bear. When Balliett returned to San Antonio after finally completing his bachelor’s in 2007, he schemed to get to New York by any funded means necessary. The golden opportunity: Juilliard’s nascent Historical Performance program, often shortened to Juilliard415. During college, Balliett had dabbled in Baroque bass with the Harvard Baroque Orchestra, whose director, Robert Mealy, had recently left Boston to teach Baroque violin at Juilliard. (Mealy would later ascend to direct the program, a post he has now held for more than a decade.)

Balliett landed in New York City in the fall of 2010. At the time, Juilliard415 hadn’t yet become today’s high-octane, all-consuming baptism by fire. The program afforded Balliett plenty of leeway to also maintain his modern-bass chops, and he was often tapped for the cerebral, hard-to-crack avant-garde music that many conservatory students won’t touch.

Balliett graduated from Juilliard in 2012, immediately assuming another coveted (and funded) position as a fellow in Carnegie Hall’s Ensemble ACJW (Academy of Carnegie, Juilliard, and Weill), known since 2016 as Ensemble Connect. The program’s intensive curriculum of chamber music, arts entrepreneurship training, and teaching in New York City’s public schools kept him plenty busy, but he still found time to gig on gut.

By 2014, he had become New York City’s first-call Baroque bassist. Sure, he was playing with the city’s few established early-music organizations, but Balliett and his Juilliard cohort were founding new ensembles that refreshed a tired scene with verve and edge: New Vintage Baroque devised thematic, scripted programs around myth and literature; the ACRONYM ensemble infused fantastical chamber music of Italy and northern Europe with chrome, brazen luster.

“Doug approaches a bass line with maximum funk,” says ACRONYM violinist Edwin Huizinga, who teaches at Oberlin. “He understands a continuo player’s deep responsibility to play rhythmically, and he’ll catch anything you throw at him — that’s why we can have so much fun with ideas and improvisations.” Indeed, even with an all-star group like ACRONYM, it’s easy for a listener to tune everything else out and just listen to Balliett’s spirited bass lines.

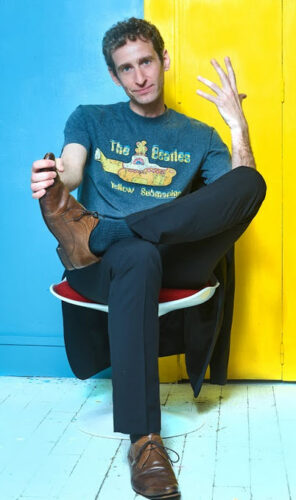

European ensembles soon took note of New York’s early-music revolution. Les Arts Florissants conductor William Christie began inviting Balliett and his collaborators to share their vitality during the annual summer festival at his Versailles-ish estate. Balliett still makes the trek to the French village of Thiré every summer to jam with some of his best friends, among them lutenist Thomas Dunford, the soulful McCartney to Balliett’s brainy Lennon — as they each professed their Beatlemania in separate interviews. (For more about the unstoppable pair, check out the May 2023 issue of EMAg, with Dunford on the cover.)

Most of all, Balliett and his cadre questioned the notion that “historically informed” ensembles should only perform historical music. Balliett had begun to experiment with works that fused lighter, Baroque-style voices and period instruments with elements of hip-hop and rap using his own poetry. He narrates each myth with the animation of a veteran fabulist, where his lax yet precise rhythmic lilt highlights a keen sense for rhyme and poetic meter. The vocalists occasionally interrupt with tender, crunchy ariettas of passion and woe, but they double as wordless, pop-style backup singers. Instrumentalists provide an inexorable groove and drama-heightening interjections, and just as Balliett’s vocals float above, he anchors from below — he multitasks his intricate libretti with his cantatas’ bass parts.

Balliett composed five rap cantatas during his season as composer-in-residence, 2013-14, with New Vintage Baroque. The first, a modernized take on Ovid’s myth of Diana and Actaeon, garnered praise from The New York Times for its “emotive precision” and “contemporary twists.” Ovid-based rap cantatas have become refrains in Balliett’s musical life, so much so that he’s now lost count of how many he’s written. They formed a pillar of his composer residency at South Carolina’s Spoleto Festival in 2018 and appeared in cheeky installments that he made with his brother while in upstate New York quarantine, circa April 2020. And when Les Arts Florissants began to experiment with pandemic-era streaming, they brought Balliett across the pond to record six of the mythological works. You’ll never see William Christie bob his head more vigorously. (Playing the harpsichord, Christie made his St. Mary’s debut with Theotokos at a Sunday Mass this past November.)

Rap cantatas on Ovid, a refrain in Balliett’s musical life

Even as he was taking the Baroque world by storm, Balliett never gave up modern bass. After his work with Carnegie’s ACJW, he was a regular on the top tier of New York’s avant-garde circuit. He’s largely left that sphere now, though he still maintains strong ties to the American Modern Opera Company (AMOC or “Amuck”), the acclaimed collective where, as the Boston Globe puts it, “the boundaries between disciplines go to die.” (AMOC gave the workshop premiere of Balliett’s second opera, Rome is Falling, at the Ojai Festival in 2022.)

“When we founded AMOC, there was no other bassist under consideration. I mean, Doug is so much more than a bassist,” says composer Matthew Aucoin. “Today, we often refer to artists as the 21st-century version of a historical composer or performer. With Doug, it’s the reverse — he’s like if Bob Dylan were actually a medieval troubadour.”

That Balliett channels the great rockers of the ’60s is no coincidence. Several sources call him a rock-n-roll encyclopedia, knowledge he brings to the stage and also the classroom. Doug and brother Brad are currently teaching a Beach Boys survey for Juilliard Extension evening classes, following on an exhaustive three-year course which examined every recorded Beatles song. Together, the twins are also collaborative composers. They are two pieces of the “part band, part book club” Oracle Hysterical. They partner for Carnegie Hall lectures and as hosts at New York’s classical WQXR.

“It’s great to be able to share so much,” says Brad, now co-artistic director of Decoda, an Ensemble Connect alumni group. “We can anticipate each others’ moods, our strengths, the things that complement each other so well. We got into a rhythm with teaching.”

Perhaps no one was keeping closer tabs on Balliett’s ascent than Juilliard. In 2017, the school’s inaugural Baroque bass professor, Rob Nairn — Balliett’s teacher — returned to his native Australia for a university post in Melbourne. The search committee agreed that Balliett was made of the same stuff.

“It was an obvious choice,” says Benjamin Sosland, provost and dean at New England Conservatory, who previously served as Juilliard415’s founding administrative director. “Balliett exemplifies the kind of musician that’s a model for the future. He’s a brilliant thinker, an incredible player, a composer, a convener. He became our consensus choice after not very much deliberation.”

The Juilliard professorship is easy to balance with the post at St. Mary’s, but the two regular jobs have eaten into his gig life. It’s all for the best, Balliett says — he can prioritize being at church each weekend. He hasn’t had to completely sacrifice his social life, but the church residency has turned him into a person who forgoes parties to stay home and read. Balliett is a self-professed history nut, currently crawling through his own primary-source world history curriculum.

“It’s all so incredibly nerdy,” he says, acknowledging the dorkiness that makes him so tangibly cool. “But it makes me a better teacher of Baroque music.”

‘It’s all so incredibly nerdy,’ he says, acknowledging the dorkiness that makes him so tangibly cool

‘Not the end of the world’

Seated at the organ last June, Balliett played the first notes of the Trinity Sunday service. In his left hand, he held a C-major drone. In the right, he notated an intricate, almost medieval melody, full of ornaments. The tune had clearly started as an improvisation, and though he had meticulously committed it to the page — as he does with all his church music — he had left himself room for an extra flourish.

Balliett’s church services each show a cross-section of his musical influences. One moment, they ripple along with soft indie flow; the next, they drive forward with energy of Beatles or Stones. He’ll pilfer an Amen from Sibelius, quote Telemann in a serene flute accompaniment. And it’s all so much fun to sing, even if Balliett’s labyrinthine harmonies occasionally challenged basic ear-training skills.

About eight bars into Balliett’s Trinity Kyrie, the accompaniment stopped. I sang a simple bit of chant, and the parishioners rustled with recognition. The mighty crowd responded to my call, repeating the melody. Balliett later told me that this was a chant from the dark green prayer books that lay on every pew. There was some trepidation among the congregation when he first arrived at St. Mary’s — the previous organist had played the same green-book tunes every week. But as Balliett began to weave the familiar into his own compositions, the parishioners warmed up.

“Doug is brave, and so comprehensive,” says Father Andrew O’Connor, St. Mary’s principal pastor and the catalyst for Balliett’s on-going residency. Back in 2019, he’d invited Balliett and ACRONYM to produce the premiere of Gawain in the sanctuary’s brick-lined undercroft. (The opera remains a New Year’s Eve tradition: show at 8 p.m., followed by a raucous party fit for King Arthur himself.) Soon after places of worship reopened in June 2020, O’Connor and Balliett hatched the current residency; the church’s sprawling balcony made an ideal space for socially distanced music.

For those first services in the fall of 2020, Balliett wove Biber’s fiendish Rosary Sonatas in with his own music. In fact, his job is as curatory as it is compositional. Around his new compositions, Balliett programs a motley array of whatever he pleases. For Trinity Sunday, he pulled out his modern bass and sight-transcribed verses of cryptic Messiaen méditations alongside organist Elliott Figg, an incredible feat of sightreading and intuition. Another week, Theotokos closed the service with a movement of Bach’s G-minor Sonata for viola da gamba. One of the players had just received a massive tenor viola from a luthier in Spain, and Balliett was eager to help break it in. “Bach was just the same way!” he exclaims. “There’s a great corno da caccia player in town this week? Come on down to the Thomaskirche!”

Most of all, collaborators say that Balliett has made St. Mary’s a safe space. His Saturday evening rehearsals aren’t the strict, perfection-driven stress inducers so common in the classical world. Instead, they’re a chance to tinker over a beer or two, to explore new ideas with an open-hearted group dedicated to radically authentic music-making.

Violinist Manami Mizumoto, a frequent concertmaster with the Bay Area’s Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, has been playing at St. Mary’s since the very first Rosary days. “Doug has this low-key way of building community — it’s very organic,” she says. “And it creates space for me to show up as just myself.”

“Those St. Mary’s rehearsals are like music therapy for his band of friends,” says Clay Zeller-Townson, artistic director of the continuo band Ruckus (of which Balliett is a founding member). “Last time I was there, the day had totally depleted me, and it was like settling into a warm bubble bath.”

“I want my musicians to know that these are the lowest stakes,” says Balliett. A couple of the anthems we sang on Trinity Sunday did careen a touch out of control, but Balliett rollicked through them all the same, his joy never waning. “We want it to be good,” he says, “but if we crash and burn, it’s not the end of the world.”

Along with St. Mary’s, Balliett has big projects lined up for the coming season. Gawain will get its first recording, and Balliett’s second opera, Rome is Falling, goes into workshop productions with AMOC this summer. He has more commissions each year for Les Arts Florissants, most recently a Medea cantata for Arts Flo vocalists Emmanuelle de Negri and Marc Mauillon. And Theotokos is starting to break out of St. Mary’s walls — they’ll give several performances around New York City this year, including one on Gotham Early Music Scene’s stalwart series of Midtown Concerts.

As his residency has progressed, Balliett has realized that his activities at St. Mary’s are acts of service. “My job here is to deepen the parishioners’ experience,” he says. “It’s not about me, and it’s certainly not about some crazy project. It’s about trying to make their Sunday as awesome as possible. And that’s liberating.”

Emery Kerekes is a writer and arts administrator based in New York. Winner of the 2022 Rubin Prize in Music Criticism, he works in The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of Live Arts.