A violinist-dancer shares tips to aid instrumentalists and vocalists

Studying how baroque dance and music fit together has given me a much stronger understanding of the dance types: their forms, their phrasing, their general character, and appropriate tempi for them. This helps me when approaching a new piece because I can quickly analyze whether this is a normal example of a dance type or one with unusual characteristics to acknowledge and highlight. Even though I would never consider myself a dancer, I still refer to the basic steps and the way they feel, their sense of weightlessness or gravity, suspension or propulsion. Close study of baroque dance also helps me recognize the dance types in music not specifically labeled as such, giving me an immediate sense of how they should be played. By embodying a cultured person of this period through dance, we gain insight into the baroque mindset and experience.

– Allison Monroe, Case Western Reserve University graduate, baroque violin

It’s as if you told me there is no Santa Claus!

– Reaction from a student after a discussion of the sarabande rhythm in which I revealed

that the second beat in a danced sarabande is not usually the most important one.

By Julie Andrijeski

By Julie Andrijeski

As long as I can remember, I’ve been a violinist who also danced, although until the age of 18 I must admit I really wanted to be a ballerina. I just loved to move to the expansive musical strains of Chopin, Tchaikovsky, and even Shostakovich that my mother chose to play for our dance classes. So when I was introduced decades later to the enticing world of baroque dance at the Baroque Performance Institute in Oberlin, OH, as a budding baroque violinist, I felt I’d come full circle. It was a natural fit. After that, I pursued baroque dance with a vengeance, earning my way to workshops by offering to accompany some of the dance classes in exchange for tuition and studying with as many teachers as I could find.

Since then, I have found many opportunities to teach baroque dance from a musician’s point of view at Case Western Reserve University, The Juilliard School, and elsewhere. Sharing my craft through the eyes of a violinist-dancer has given me not only great pleasure but also an increasing awareness of how illuminating baroque dance can be to musicians in general, and how relevant it is to our understanding of movement, form, phrasing, and gesture in music.

Aspects of baroque dance can also inform our instrumental and vocal techniques. Merely adopting the natural stance as it is described in the dance manuals, for instance, aligns the body in a way that is most beneficial to music making. Step-units-movements that connect the various leg bends, rises, turns, and jumps into a larger gesture-provide much food for thought when shaping sounds with the bow or with air speed. The combination of bends and rises in specific dance steps can correlate to, say, the management of bow and breath maintained throughout a short musical gesture before it is released.

The Simple Step

Baroque dance is merely a stylized version of basic natural movements: walking, running, jumping, hopping, sliding, turning, even falling. Toward the beginning of many dance treatises, there are tables showing codified symbols for all of these movements. At the root of each is the simple step, or pas. It’s amazing how much this ordinary step can heighten our sense of movement in both dance and music.

Baroque dance is merely a stylized version of basic natural movements: walking, running, jumping, hopping, sliding, turning, even falling. Toward the beginning of many dance treatises, there are tables showing codified symbols for all of these movements. At the root of each is the simple step, or pas. It’s amazing how much this ordinary step can heighten our sense of movement in both dance and music.

A simple everyday step is a gesture in and of itself. It begins with a release of the heel as the foot moves forward, an arrival onto the new foot, and a resolution as the body rebalances itself. At every stage in this step, there is an ever-changing velocity of motion, and a sense that movement flows from somewhere to somewhere. Steps are buoyant and fluid, yet there are little impulses in a simple step that relate to beat hierarchy (a light pulse to begin the release followed by a stronger action when the step is taken). Lastly, like virtually all movement, the simple step illustrates the importance of constant fluctuations between tension and release, action and reaction, and ebb and flow (tension builds as the new foot approaches its destination, after which tension dissipates).

All of these elements within a natural step are amplified in baroque dance. The baroque version of the simple step, the demi-coupé, increases the distance between low and high levels of the body by the addition of knee bends and rises onto the toe; and the differences in velocity from bend to rise alternate more dramatically according to the character, tempo, and beat structure of each dance type. The fluctuating velocity, non-linear tension, and release within a prescribed beat hierarchy are all crystal-clear when this step is put into action.

And just as there are myriad ways to play a simple quarter note, the demi-coupé can elicit many moods according to the character of the dance.

Julie’s classes have brought together students in dance, music, and history who normally don’t cross paths or see how their studies relate to each other. Even in just one or two sessions, the musicians who work with her have all enjoyed and benefited from experiencing the movements and gestures of dance.

– Joseph Gascho, University of Michigan, keyboardist

The simple step, both in its natural and stylized forms, can deeply impact our general music making. When sculpting musical notes into gestures, for instance, think about how subtleties in bow (or air) speed and pressure can add variety and shape. When playing even the staunchest march or most fleeting passepied, dance reminds us that there is always tension and release, action and reaction, and ebb and flow-and that movements are curved (buoyant) rather than linear.

Movement

In baroque dance, strong beats are emphasized by a rise on the toe rather than a step into the ground. This is perhaps the most important piece of information, since it gives musicians a sense of the buoyancy, grace, and lightness of movement even in the most raucous gigue or rigaudon.

Taking baroque dance classes adds such a depth to the music I play. The experience of trying out steps and combinations informs the way I direct energy in my music and governs the structure of my phrasing.

– Melanie Williams, Juilliard DMA student, baroque flute

There is always a preparatory impulse-usually a bend-before the main action, which almost always occurs on the downbeat and is the strongest, most linear movement in the measure. The velocity of a preparation increases as it nears the action. This may seem to warrant a crescendo in the music.

Baroque dance teaches us that this is not the case. The preparation for virtually all baroque steps comes from the bend, which is a release. The dancer remains in the bend with the heel of the standing foot on the ground throughout the preparation, and though her body anticipates the action to come, she waits until the last minute to rise on a strong beat. It is, then, the gesture from low bend to high rise, although connected with an increase in velocity and always with a sense of fluidity, that produces a non-accented preparation-much like a singer taking a breath-into an accented action.

Usually, step-units do not cross over the bar line. (One big exception is the basic menuet step, which spans two measures of 3/4.) Paired with the idea of a prepared main action on downbeats, this leads to the need for an articulation, no matter how small, on nearly every bar. This articulation can be quite subtle, almost undetectable, but it is essential to the cadence of the dance, and to its buoyancy.

In baroque dance, even the most static moments have movement. It could be as subtle as a shift of the eyes or a slight adjustment of the head, arms, or body. This shift can be the most powerful moment of a dance. With this in mind, consider the small silences between notes within a musical phrase. Feel movement, no matter how small, between every bow stroke, key strike, or articulation. Play the rests, keeping them alive, whether they add tension or provide release.

It is interesting to note that the dancer sometimes moves quite actively through a long note. This frequently happens on the last held note of the dance. For musicians, this means two things: the last note needs to have a meaningful shape to successfully end the composition, and the music cannot slow down too much into the last note since this would leave the dancers a bit stranded.

Dance is a defining element of Baroque music. It is an unparalleled experience to work with someone who can explain rhythmic figures, phrasing, and tempo. But to take it a step further, gaining a mental picture through demonstration, seeing how music occupies space, and learning how to dance yourself are unforgettable experiences and a bottomless guide in deciphering our music.

– Carrie Krause, Juilliard graduate, Concertmaster of the Bozeman Symphony, violin

Cadence and Rhythmic Interplay

The term “cadence” has many meanings. Here, I will use it in reference to the general movement and character of each dance type or step. Understanding cadence is a crucial element in playing dance music, both with and without dancers.

Each dance has its own cadence. The bourée is simple, light, and fleet, the menuet also simple, yet more stately and refined, while the sarabande and the loure are more quixotic in their movements, playing to deeper and more complex emotions.

Dances also have their typical musical gestures and step-units. The rigaudon, for instance, often begins with two half-notes followed by a dotted-half (stasis, tension) and concluding with a more active passage of quarter and eighth notes (movement, release) that includes a turn figure coinciding with the rather sassy rigaudon step. Gavottes provide a sense of cross-rhythm and jauntiness due to the canon- like use of quarter-, quarter-, half-note movement in the music against half-, quarter-, quarter-note movement in the dance. And the (French) gigue is made up of many dotted (sautillant) rhythms for both dancers and musicians, although the dancers’ pacing of the rhythm is twice as slow as that in the music, again causing a sense of cross rhythm.

like use of quarter-, quarter-, half-note movement in the music against half-, quarter-, quarter-note movement in the dance. And the (French) gigue is made up of many dotted (sautillant) rhythms for both dancers and musicians, although the dancers’ pacing of the rhythm is twice as slow as that in the music, again causing a sense of cross rhythm.

Passepieds provide us with the clearest example of cross rhythms. They include hemiolas within a phrase that are indicated in the music by a change in meter, usually from 6/8 to 6/4. Oddly, the passepied choreography completely ignores this change of meter, and the dancer continues the same step, dancing “against” the hemiola. This can be quite disconcerting, even for the most experienced dancers, but I must admit it is exhilarating to find myself once again on the beat after the hemiola passes!

Phrase Structure

There are certain basic patterns I’ve come to expect in dance music and choreographies. For typical bipartite dances (for instance, bourées, menuets, sarabandes, and gigues), phrases are based on balanced groupings, typically some sort of four-part structure: 1+1+2, or 2+2+4. In the second half of the piece, the phrases are often longer, 4+4, or even 8-bar phrases. The four-part phrase is neat and tidy, symmetrical, balanced, reliable, expected, much like the manicured gardens at Versailles. It has four discernible parts: an action, a reaction, a contrast, and a cadence. Particular dance steps punctuate these phrases: resolute jumps end strong cadences, for example, while softer slides and steps ending up on the toes mid-measure illuminate the imperfect and half-cadences.

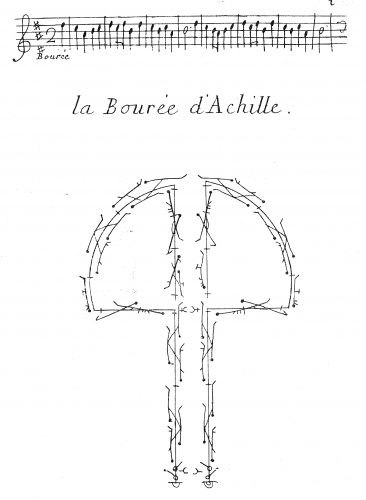

In the case of the popular couple dance Bourée d’Achille, the opening sequence consists of a pas de bourée forward (action), another pas de bourée forward beginning with the opposite foot (reaction), followed by a more energetic step (contretemps de gavotte) that breaks to the side, away from each other, and then ends with a calmer cadential step consisting of a step and a slide (pas coupé) that highlights the end of the A section without closing it off.

Knowing the steps, the structure, the stresses, and releases to dances like sarabande, gavotte, menuet, etc., totally changed my way of playing them. Decisions about tempo or articulation are now taken from the perspective of the dancer. All of a sudden music becomes tangible, physical; I can feel the cadence in my body and relate those feelings to the music’s character and affect.

– Karin Cuellar, Case Western Reserve University graduate, currently studying at the Royal Academy of Music, baroque violin

Perhaps the single most helpful instance of baroque dance in helping violin playing was working with Julie on the Bach loure from his Third Partita for solo violin. The dance steps clarified the rhythmic groupings, tempo, and phrasing. I was shooting in the dark on how to approach this piece, and the answers were all in the choreography.

– Carrie Krause, violin

This is not to say that most dance phrases are strictly divisible by four; in fact, the contrary is true. Yet we’re conditioned to hear phrases this way (just tune in to a popular-music station to get a good dose of the practice). Only based on these expectations can we enjoy the anomalies that arise to disrupt our comfort zone. A five-bar phrase-Wow! How might the savvy choreographer handle the extra bar? Perhaps he uses repetition by repeating a step-unit, employs placement by taking the dancers farther away from each other, or simply inserts an unexpected step or turn.

Form and Structure

It is important, and musically interesting, to play the form. By this I mean the musician should know which part of the formal structure he is playing at all times. Baroque dance, when choreographed well, illuminates this form and structure by providing us with a 3D analysis of the form.

From a bird’s-eye view, the baroque dance notation such as the example shown in the Bourée d’Achille immediately reveals the basic shapes that make up the dance. The steps along these shapes outlined so beautifully on the page show to a great extent where the dancers are in the room at all times. Straight and curved paths often alternate, and active jumps and hops along the way might transition into smooth turns and glides. In the ballroom, only one to two dancers perform at a time, utilizing the entire grand space. They usually perform in mirror image-in opposition to one another-throughout the dance.

Most choreographies are through-composed, even when the music is not. In other words, a choreography set to a bipartite dance air may have a completely different set of steps, with subtly different phrase lengths, for the repeat of the A section. Many dances are played twice through, including all repeats, and most often these steps are newly composed. This provides subtle differences that the musician can reflect in his second rendering of the tune, perhaps linking two formerly distinct phrases into a longer phrase, or changing character using different bow strokes, or adding more or less articulation. I suggest adding ornaments only as a last resort, and with taste, in these situations.

The positioning of the dancers on the dance floor can be extremely informative to musicians as we consider the form of a dance air. If the dancer wants to say something powerfully extroverted, he/she will rush downstage and dance at the very lip of the stage, or near the highest-ranked people in the ballroom. This often coincides with sections of the form that are furthest removed from the tonic key and/or are the most active. If the mood is more simmering and held, the dancer may be mid-stage, turned partially away from the audience. During moments of repose the dancer may back away from the audience, and toward the end, you most often see the dancers recede to the back of the room where they started.

Tension and release can be palpable within the framework of the dance. Two dancers may begin in an easy camaraderie side by side, but then tension arises when they peel away to opposite corners of the room, only to reunite again (release) mid-floor. Many dances play with this flirtatious, and sometimes downright steamy, element, providing an additional level of tension and release that can be reflected in the music.

Julie Andrijeski is a performer, scholar, and teacher of early music and dance. A faculty member in the Music Department at Case Western Reserve University, she teaches early-music performance practices and directs the Baroque Music and Dance Ensemble. She has given baroque dance workshops nationwide, including at The Juilliard School for historical performance music students. As violinist, she appears regularly with Apollo’s Fire and Les Délices in her hometown of Cleveland, Ohio, and travels extensively throughout the States and abroad, performing with the Atlanta Baroque Orchestra (Artistic Director and Concertmaster), Quicksilver (Co-Director), and many other early-music groups.

Julie Andrijeski is a performer, scholar, and teacher of early music and dance. A faculty member in the Music Department at Case Western Reserve University, she teaches early-music performance practices and directs the Baroque Music and Dance Ensemble. She has given baroque dance workshops nationwide, including at The Juilliard School for historical performance music students. As violinist, she appears regularly with Apollo’s Fire and Les Délices in her hometown of Cleveland, Ohio, and travels extensively throughout the States and abroad, performing with the Atlanta Baroque Orchestra (Artistic Director and Concertmaster), Quicksilver (Co-Director), and many other early-music groups.