In 1954, with playable instruments in hand, a collective of Boston musicians started experimenting with early repertoires from a remote musical world

Camerata founder Narcissa Williamson ‘loved to talk about the beauties of music none of us had yet experienced adequately’

American colleagues were skeptical of the Camerata’s fondness for Medieval music just as European colleagues were skeptical of its exploration into Americana

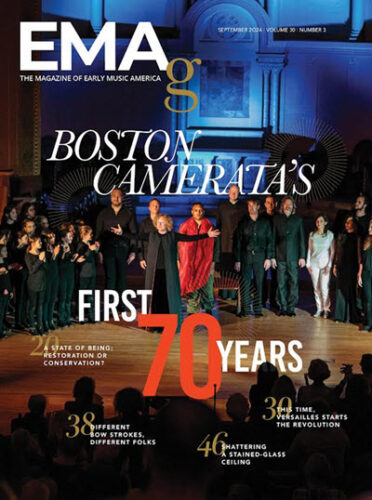

The Boston Camerata, celebrating a remarkable 70th anniversary in 2024-25, continues to push our understanding and acceptance of what constitutes “early music.” Long before it was cool in America, the ensemble made Medieval music central to their repertoire, and this season they’ll highlight that centrality with one of their signature programs, A Medieval Christmas.

The show’s perennial popularity, and a landmark 1974 recording, helped elevate the Camerata to national and international prominence, with hundreds of performances and an LP that sold more than a hundred thousand copies. From a traditional Jewish cantillation (“Isaiah’s Prophecy”) and 10th-century Old Saxon Gospel reading (“On frymðe wӕs Word”) to plainchant and hymns of Provençal, Dutch, and Italian origin, it was a musical feast of reverence and awe, a curated narrative of the Nativity.

Soprano Anne Azéma, who sang in her first A Medieval Christmas in the 1980s while still a “very green” student at New England Conservatory, created her own version, updated from the Camerata’s original 1970s program which was devised by Joel Cohen.

Now 82, Cohen led the Camerata from 1968 to 2008 and is the group’s artistic director emeritus. In a (mostly) seamless transition, Azéma — she and Cohen are married — became artistic director in 2008. Starting with an LP titled Monteverdi: Scherzi Musicali in 1968, the ensemble has cut more than 50 recordings on a variety of labels, including the first Dido and Aeneas on period instruments. Indeed, like their concerts and international tours, many of their award-winning recordings were “firsts” in some significant fashion.

Azéma sees their two iterations of A Medieval Christmas, separated by a half century, as having “everything and nothing” to do with each other. “The idea of the program is still there, some of the major pieces are still included, [but] the performance practices have changed a lot, and the configuration of the ensemble has changed a lot,” she explains.

While Cohen’s original A Medieval Christmas featured four singers and four solo instrumentalists supported by the ensemble, for example, Azéma’s program is performed by just three treble voices, vielle, harp, and winds, with a smattering of hurdy gurdy and percussion.

Today’s performers benefit from what Azéma calls, “to put it bluntly,” a “technical fluidity and efficiency that wasn’t as available to players in the ’70s who did not have the benefit of highly practiced mentors.”

From tragedy to revival

To mark their 70th, Boston Camerata will engage with their history on many levels. In October, they begin the season by returning to the nest with a concert at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), where Cohen was preceded by another visionary, Narcissa Williamson, a staff member in the museum’s education department and an amateur viol player.

In a tribute to Williamson that he wrote for the Boston Globe shortly after her death in 1986, Cohen described the ensemble’s humble origins: Williamson “could have been mistaken for the stereotypical, timid museum employee or archivist. And the dark, unattractive basement space where the Museum of Fine Arts had seemingly dumped both her and the Galpin Collection of Musical Instruments did not seem a likely place from which to shape and influence America’s cultural history.”

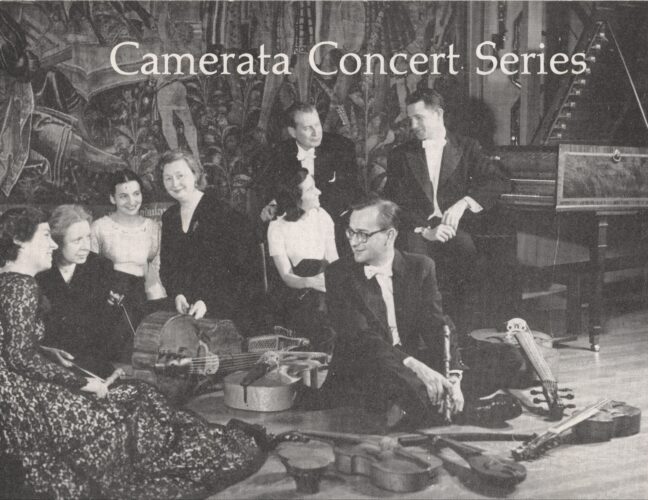

In 1917, Boston businessman and museum trustee William Lindsey donated 560 instruments to the MFA in memory of his daughter, Leslie, who perished in the sinking of the Lusitania. Collected from around the globe by English clergyman and amateur organologist Francis W. Galpin, these cultural artifacts had languished in that “dark, unattractive basement” for decades. Williamson dedicated herself to a seemingly strange idea: What if those instruments were made to speak again?

Williamson persistently nudged the museum higher-ups until they agreed to fund the restoration of instruments in the collection and the creation of reproductions. And “she encouraged a whole generation of young instrument-makers to set up shop around Boston,” Cohen continued. “The Hubbards, Dowds, von Huenes, and Warnocks of that time learned from the Galpin Collection.”

With playable instruments in hand and two singers on board, a collective of local musicians started experimenting with early repertoires from a remote musical world, one that predates celebrated 18th-century figures like J.S. Bach and Antonio Vivaldi. In 1954, that collective became the earliest iteration of the Boston Camerata.

Although impractical to mention all the many luminaries, living and dead, who were involved in the Camerata’s earliest years, many will be recognizable to the historical performance community: Alongside Williamson on the viol were players and scholars including Howard Mayer Brown, Thurston Dart, Judith Davidoff, David Fuller, Anne Gombosi, Daniel Pinkham, Charles Fassett, and others — a long list. They were paid $5 per rehearsal and $25 per concert.

The earliest public presentations were at times ‘more symbolic or ritual than artistic’

Still, in his Globe tribute to Williamson, Cohen described an ensemble that was at times more interested in experimentation than presentation. “That the music we loved and rehearsed in the MFA’s lower depths was to be made public was an essential part of our collective project, but the nature of those public presentations was at times more symbolic or ritual than artistic. For one thing, the instruments we played were as yet imperfectly mapped by their practitioners.” He goes on to describe a 1964 performance during which the group had to re-start Josquin’s “Allegez-moi” at least three times before making it all the way through.

Cohen’s tribute leaves the impression that Williamson’s great gift was the rare ability to devote herself wholeheartedly to something that could only be imagined: She “loved to talk about the beauties of music none of us had yet experienced adequately.”

‘Medieval music doesn’t exist’

In 1968, perhaps the most tumultuous year of a paradigm-shifting decade, Cohen, a budding composer and lute player still in his 20s, returned from studies in Europe, where his teachers included legendary pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. Invited to join by organist Victor Mattfeld, he became the Camerata’s new leader the next year. Five years later, as the ensemble parted ways with the museum, Cohen led the effort to build an independent board and secure funding.

Although reveling in the rebellious, anti-establishment spirit of the times, many of the historically minded musicians in the 1960s and ’70s who joined the nascent early-music revival were reluctant to explore a broad and inclusive repertoire.

In this precarious situation, without institutional backing, Cohen might have played things safe, sticking to music that would signify that the newly independent Boston Camerata was a “serious ensemble” deserving of concert bookings, recording contracts, and financial support. But instead of narrowing his focus to a handful of well-regarded manuscripts from the Western European tradition, Cohen also looked backward and outward, applying his research skills to explore music across dozens of cultures, spanning several centuries and several continents.

This included his own burgeoning interest in Medieval music. “I remember one Camerata business manager saying ‘How can you do this Medieval stuff? It’s never gonna appeal to anyone,’” Cohen recounted with a chuckle.

“In the 1970s,” Azéma told me recently, “Camerata was doing a kind of programming that was absolutely poo-pooed by many Europeans and some Americans.” But as they would do in so many other areas, Cohen, Azéma, and the ensemble found value in music and mindsets that others hadn’t. They had a knack for anticipating, and steering, the trends that later came to seem essential to our understanding of an ever-expanding field. (It’s a pattern repeated elsewhere: In the early ’70s, Cohen spent two years working as a radio producer for France Musique where he had the idea for a national musical celebration, in all genres, on the summer solstice. Now beloved in France as Fête de la Musique every June 21, it’s spreading globally into World Music Day.)

But pushing boundaries is most likely to set a trend when it also captivates the listener. “When I was a young teenager in the mid-’70s, while others were listening to Led Zeppelin, I had a Boston Camerata recording which I listened to often,” recalls early harp and wind player Christa Patton. “There was one track with a crumhorn quartet playing Mainerio’s ‘Tedesca e Saltarello’ that I particularly loved — I played it over and over again. Not too long ago, I found myself playing that same dance with the Boston Camerata. My inspiration turned into my reality.”

One ongoing puzzle concerns concert personnel, which Azéma calls “a wobbly situation.” She says today’s logistical and financial requirements for concerts and recordings “demand certain choices, which are not necessarily representative of the musical context.” When they recorded A Medieval Christmas in 1974, Cohen’s ensemble — four singers, four instrumentalists, plus ripienists — stemmed from the classic madrigal consort formation.

“This configuration question was at the center of Camerata’s growing pains in the early to mid-’80s,” Azéma says, as Cohen had chosen to assemble each roster of musicians to meet the demands of the various repertoires. “For me,” Azéma continues, “it became obvious that this early consort-like configuration would not hold, for many reasons — of repertoire, periods, and mixed consorts, chief among them.”

These questions, she adds, start “to become clarified when one realizes that ‘Medieval music’ does not exist, but that we perform several medieval repertoires, which all need to be served with appropriate knowledge and practices. This wasn’t the case in the ’70s.”

At the frontier

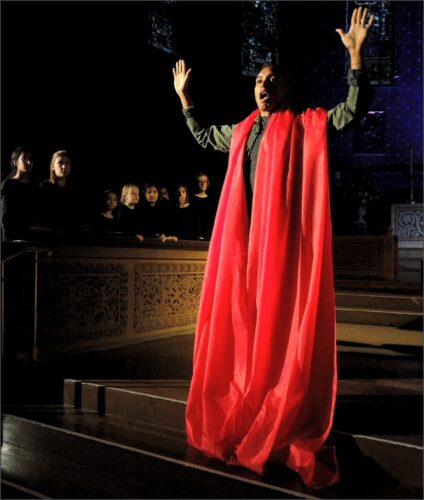

In addition to their A Medieval Christmas, the ensemble’s 70th season includes a revival of another flagship program, The Play of Daniel.

As Azéma puts it, “Daniel is a river that runs through us.” Camerata will perform Azéma’s re-edited and highly staged version updated as Daniel: A Medieval Masterpiece Revisited. Created in 2014, it was conceived in response to Cohen’s 1983 edition and production. The ensemble’s relationship with the piece dates back to the 1960s, when they first performed an edition by Noah Greenberg, who led the influential New York Pro Musica.

For a time, NYPM, with countertenor Russell Oberlin as their star attraction, were the defining early-music ensemble in the U.S., setting the agenda for music that stretched from the oldest known English songs to Handel arias, highlighted by their own Play of Daniel, broadcast for many years as a Christmastime tradition on television. Cohen calls Greenberg, who died in 1966, “my first model for early-music performance.”

But while American colleagues were often skeptical of the ensemble’s fondness for the Medieval, their colleagues in Europe, where the Camerata had begun touring in the 1970s, were skeptical of its exploration into Americana. A concentrated interest in early American music and cultural expression is another instance of the Camerata being among the first to crack open what, today, seems like natural repertoire for a U.S.-based ensemble. And it led to some of their most rewarding collaborations, especially with musicians from non-classical traditions.

In 1995, the Camerata released the album Simple Gifts, which dives into 18th- and 19th-century songs from the American Shaker tradition. Cohen’s interest in early American music dates back to his days as a graduate student in composition at Harvard. He recalls that his mentor, composer Randall Thompson, introduced him to “the vital, atavistic ‘dispersed harmony’ of the Sacred Harp” tradition. Careful to curate a program that would preserve the “basic tenets of Shaker performance practice,” Cohen transcribed a handful of the over 10,000 extant songs preserved in the Shaker Library at the last surviving Shaker community in Poland Spring, Maine. “I was greeted warmly by Sister Frances Carr and the other Shakers,” Cohen reminisces; he now calls the Camerata’s recordings and concert appearances alongside the Shakers “a precious chapter of our ensemble’s story.”

No one could have predicted that, nearly a decade later, Simple Gifts would launch a partnership with, of all things, a contemporary ballet company in Finland. Finnish dancer Tero Saarinen happened upon Simple Gifts in a record shop, and it served as the basis for his ballet Borrowed Light (with a spirit clearly drawn from the Aaron Copland-Martha Graham ballet Appalachian Spring).

In Borrowed Light, the Camerata provides live music while members of the Tero Saarinen Company dance his original choreography. The Boston Globe described it as “drawing freely from the Shakers’ aesthetic of simplicity, severity, and solemnity.” By now, Camerata and the Tero Saarinen Company have performed Borrowed Light over 80 times on three continents, with performances scheduled across Europe during Camerata’s 70th season.

An interest in Shaker music exemplifies the Camerata’s characteristic exploration of music that, as Cohen puts it, is “on the frontier of so-called ‘learned music’ and oral and popular traditions.” By reputation, the ensemble had long been a leader in this performance ethos, and Azéma was keen to take up the banner upon assuming the directorship in 2008: “Camerata has never feared this way of looking at programming.”

She cites a bold and wide-ranging curiosity as one of her reasons for sticking with the ensemble for so many decades. “If the goal is only to reproduce what the generation before has done and what is now an accepted canon,” she says, “I’m not interested.”

Common ground

Boston Camerata’s record of building upon, rather than replicating, the work of their forebears is attributed to Azéma and Cohen’s complementary artistic and intellectual strengths. Frequent collaborator Allison Monroe, a historical string player and director of the Five Colleges Early Music Program, points to “the way [Joel] combined historical research with living traditions and their modern practitioners.”

But even the best research doesn’t guarantee a great concert. One must, as Azéma says, “give [the music] a context then and now.”

This ability, too, has inspired Monroe. To the Camerata’s well-researched foundation, she says, “Anne adds her unique sense of drama, a progression through emotional and musical states, and her own incomparable rhetorical skills.” For Monroe, it becomes something exceptional: “I have seen this ‘special sauce’ result in performances that both connect with audiences where they are and also lead them into other worlds.”

Time and again, Azéma and Cohen have discovered that some of these other worlds are more in parallel with each other than one might assume. For example, as Cohen explained in a 2021 interview with Thomas Forrest Kelly as part of EMA’s online Trailblazers in Historical Performance series, “the process of reconstructing the earliest melodies by Black Americans to survive in partial notation from 1870s has a lot in common with trying to reconstruct troubadour songs.”

In fact, sometimes the melodies themselves, not just the academic methodologies explaining them, share a common ground. Take Camerata’s recent We’ll Be There! American Spirituals Black and White 1800-1900, which the ensemble describes as a project that “examines early American spiritual songbooks, both Black and White, and their related oral traditions, with an enlarged, intercultural perspective.”

One melody, often referred to as “Sybil Song,” traces its origins to Medieval Spain and Provence, where it was sung to the apocalyptic Latin text “Judicii signum.” A variant is recognizable in spiritual songbooks used by Black and white communities in the 19th-century U.S., where echoes of the apocalyptic Latin text are heard in new texts about the Day of Judgment. “Sinner Man” became a common title for this tune in the Black spiritual tradition, perhaps best known as sung by Nina Simone.

The “enlarged, intercultural perspective” that transcends centuries, geographies, and cultures in We’ll Be There was evident to the New York Classical Review, which covered a recent Camerata concert, presented on New York’s Music Before 1800 series. “Which came first?” critic George Grella asked in reference to “Sybil Song” and its many iterations: “That matters not at all, as they both are part of American music, talking to each other and to us through generations.”

The Camerata, with vocalist Jordan Weatherston Pitts and gospel choristers, performed We’ll Be There at the 2023 EMA Summit in Boston and will tour the program in their anniversary season.

Their Boston-area series will also include a performance of Travl’in Home: American Spirituals, 1770-1870, which will “trace migratory currents and flows of early American song” among diverse sacred traditions, including “Puritans, Shakers, Amish, Mennonites, and newly-freed African-American religious communities.”

Travl’in Home is perhaps a microcosm of Camerata’s characteristic weaving together of the common threads that traverse music of different peoples and musical communities. Within a single program, one of many across their 70-year corpus, Camerata offers audiences the opportunity, as Azema puts it, to “touch the beauty and cries of despair, hope, love that run through human experience — to see a constancy through different grammar and context.”

Indeed, the Camerata’s greatest contribution, as much as any individual project, might be their mindset — their ethos — of investigating the whole world in early music, aligning their research skills with deep musicality and a joy in sharing the results with audiences.

Asked what it takes to last seven decades, Azéma doesn’t hesitate. “I recently learned that a Catalan early-music ensemble, Ars Musicae, was created in 1935 in Barcelona — and disappeared in 1979. There were many of these ensembles in Europe. Camerata so far is one of these pioneering groups still vividly alive and making music. Perhaps our programming choices, and curiosity towards several important corners of the repertoire, has something to do with our longevity.”

Ashley Mulcahy is a Boston-based mezzo-soprano and graduate of the Voxtet Program at the Yale School of Music and Institute of Sacred Music. She sings with numerous ensembles and co-directs her own voice and viol ensemble, Lyracle.