Newly discovered flute music by Marin Marais

An old château in the Champagne countryside, a 600-page collection, and a Paris auction lead to a significant find for Baroque flutists

‘The biggest discovery in the flute repertoire since the Telemann duets were found some 30 years ago’

In February 2023, I saw a notice about a large volume of early French flute music to be sold at auction in Paris. Reading through Drouot’s auction description, I could hardly believe my eyes: over 600 pages of music from the court of Louis XIV, printed between 1707 and 1711. The auction included books, paintings, furniture, art objects, all listed as “Provenent d’un Château Champenois,” from the Champagne region of France.

The volume, as advertised, included both published materials and music in manuscript. It was said to contain six different published opuses of Michel de La Barre, including his first and second books of suites (in their second printing) as well as four books of flute duos. There was also the first flute book of Jacques-Martin Hotteterre and symphonies of Pierre Gautier de Gaultier. In addition to the printed works, the volume held an unknown Duo by an unknown composer, a Monsieur Folio (or Foliot).

But what really caught my eye was this: Marin Marais, various pieces taken in particular from the 2nd book of pieces for viols (1701) including Voix Humaines, a Muzette, La Gratieuse. Drouot’s auction description said the Marais pieces for flute and bass were probably arrangements of pieces from his second book of music for viola da gamba — listing the three aforementioned movements in particular as being from the gamba works.

This was a stunning find. There is no known music for flute and continuo by Marais, and even if these flute pieces were merely contemporary arrangements of Marais’s existing viol music, it would be an important discovery. So I decided I must make a serious effort to acquire this volume of music. (Taken together, the collection appeared to cover most of the earliest music for Baroque flute, missing only the trio sonatas from Marais, La Barre, and additional works of Hotteterre.)

Amazingly, this was the only music-related book in a collection of hundreds of rare volumes. I got up at 6 a.m. — midday in Paris — the day of the auction to bid live online. I have often bought historical flutes at French auctions online, so the process was not new to me.

Auctions are a good way to obtain music, books, or instruments that would otherwise be out of reach. There are a number of auction houses which have special auctions for instruments. One I frequent is Vichy Enchères in France. It’s worth noting that prices can initially seem good but the end costs include a large surcharge, often as much as 30 percent, plus high packing and shipping fees.

I was very lucky that there were not more musical materials in this particular book auction. As a result, I suspect none of the usual music dealers were in attendance, which would have driven up prices considerably. Indeed, I seemed to be bidding against just one other person and, after a tense minute, I had won the hefty book without permanently ruining my bank account!

What’s a ‘flute?’

Then as now, Marin Marais (1656-1728) was known primarily for his music for the viola da gamba. As a performer and composer at Louis XIV’s Versailles, Marais wrote five books of music for viol that are masterworks of the early Baroque in France. And although you are unlikely to see them anytime soon at the Metropolitan Opera, his four tragédies en musique were important works when they were premiered, of mythology and monsters and a lot of fantastic music.

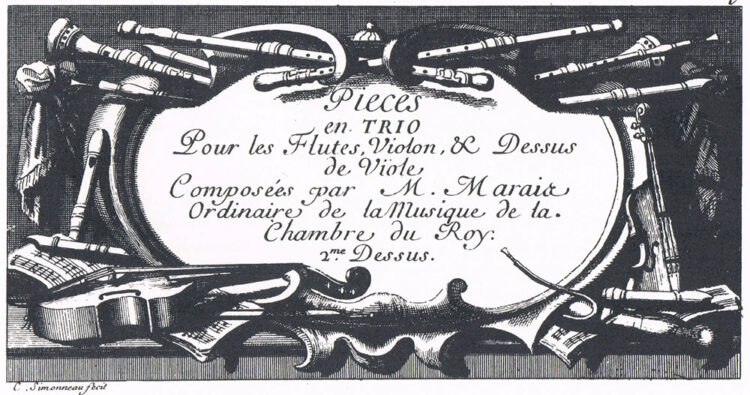

Marais was also essential in the development of chamber music, although here terminology can get confusing. His Pièces en Trio (1692) was the first chamber music published anywhere to include the transverse flute — although its title page gives “pour Flutes, Violon, & Dessus de Viole” as instrumentation.

Note that the simple term “flute” is complicated by the fact that it would, at the time, have been used for the recorder not the transverse flute, which was then referred to as the German flute or flûte traversière or, in our modern usage, a Baroque flute or traverso or transverse flute. To help unpack these definitions, if we examine the parts of the Pièces en Trio, we can see that the flute part was written to fit the range of what we’d call the alto recorder, with F as the bottom note (rather than D, the bottom note of the flûte traversière).

Yet looking at the title-page illustration of his Pièce en Trio — a work used only as an example, since it’s not part of this auctioned book — we see evidence that Marais had in mind the recorder, traverso, oboe, violin, gamba, and bassoon. These instruments do, in fact, work very well with this music. In fact, Marais is writing in a style meant to accommodate many different instruments and, indeed, I would argue that these pieces do not contain a part specifically for transverse flute.

But the Marais music in the book I’d just purchased is specifically for transverse flute. That would make it the only such music of its kind.

Same Title, Different Music

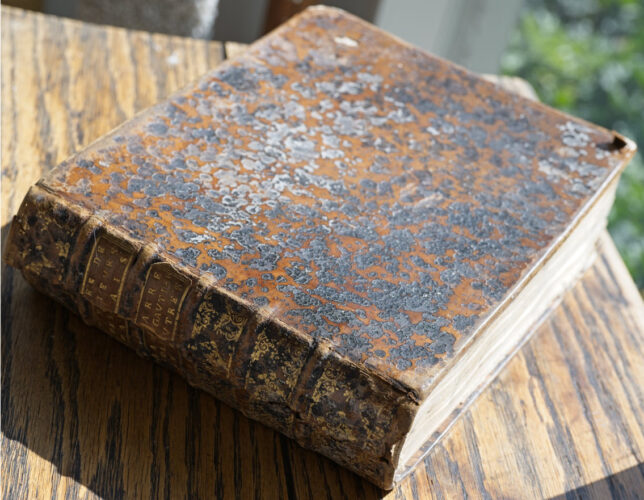

About a month later, the auction book arrived in the mail. It was a fantastic moment for me. I was surprised how thick the book is — not something you’re going to put on the music stand! Most of the paper is in excellent condition. One can easily guess what music came fresh from the publisher, such as the LaBarre pieces, and what music was previously used before being bound into the collection — the Gaultier, for example. The manuscript sections are in especially fine condition, written in a skilled and beautiful hand on fine heavy paper. Given its age, the binding is in good condition, although the spine is split.

‘I felt like I was in a dream going through the pages for the first time’

I knew and already had copies in facsimile of all of the printed works in the volume, most of which are available on IMSLP and elsewhere. Still, having the real thing in my hands was incredible — I felt like I was in a dream going through the pages for the first time! I noticed the name “La Barre” written on the cover of one set of pieces, and it has been confirmed by a French archivist that this is his actual signature. The printing of the La Barre books is exceptionally clear and readable, and I suspect these were printed when the plates were quite new.

Following the published material is a 120-page section, written in an elegant hand, which I would title “Marais Pièces pour Flûte Traversière et Basse.” Unfortunately, the actual title page that probably had similar words, as well as the first page of the first piece, had been removed from the book. This is very disappointing because it would have likely contained essential information.

My first question about this Marais music: Is it arranged from other pieces by the composer, or are these works really new (to us)?

The auction house had said it was arranged from the second viol book. I proceeded to compare virtually every piece and found only one that was common to both sources, a lovely Muzette. The flute manuscript contains two pieces, “Voix humaines” and “La gratieuse,” whose titles appear in both this flute book and also his famous works for gamba, but the music is totally different.

I spent several days playing through all 70 of these Marais movements. At first, I was disappointed that the pieces were not as complex as Marais’s works for viol. But it’s an unfair wish: His extravagant viol music takes advantage of being able to write many lines at once and can include chordal material — all but impossible for the flute. These discovered pieces are simpler, although they are extremely beautiful with amazing sarabandes and preludes. The written-out ornamentation is very expressive and skillfully crafted, often weaving together individual bits into an entirely ornamented phrase.

Interestingly, in the Preface to his well-known Viol Book 2, Marais says:

These pieces are written in a different way than those of my first book. I took care to compose them in such a manner that they can be played by all kinds of instruments, such as organ, harpsichord, theorbo, lute, violin, and German flute, and I dare to flatter myself that this has succeeded, by having tested it on the latter two instruments.

Indeed, the pieces from this collection certainly seem like they were written by someone who really played the German (aka traverso) flute. Just as Marais’s viol music is known for its beautiful melodies, these traverso works are just as excellent in that regard. Each movement has a wonderfully crafted bass line with the range of the seven-string bass viol. It is worth noting that the bass line is unfigured. That certainly doesn’t imply that these pieces are meant to be played without a chordal instrument like harpsichord or theorbo, but it could simply mean the owner of the volume didn’t need figures for how they planned to use the music — or didn’t want to pay to have them put in!

My second question was more fundamental: Where are these pieces from, and did Marais really write them?

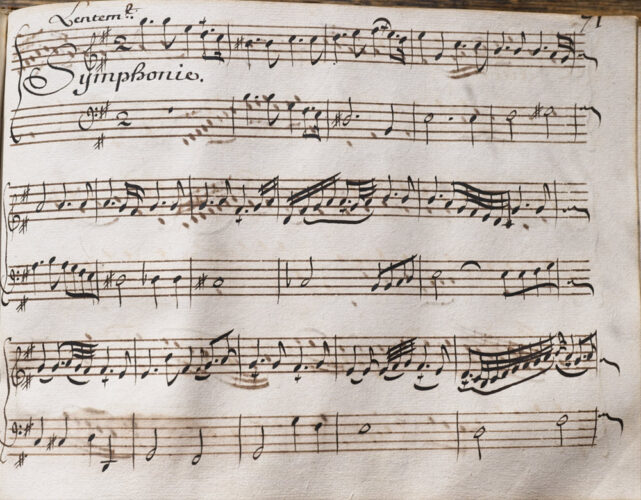

We can only make educated guesses. The movements include: Prelude, Allemande, Sarabande, Gavotta, “Voix humaines,” Muzette, Gigue, Air, Menuet (16 of them!), Bransle, “Contrefaiseurs en Echo,” Symphonie, Courante, Passepied, and Rondeau. There are many fine pieces and, as mentioned, the sarabandes are particularly sublime.

The missing title page is very unfortunate, but a number of specific pieces have Marais’s name on them. I suspect that the copyist just copied the text directly from the sources they were using. The pages of the Marais section have their own numbering, from 1-120. On page 42 of the Marais there is suddenly a title, “Pièces de Mr. Marais,” and the movement is a Prelude. Is it possible that pages 2-41 were copied from a different source, and this was the beginning of a new source?

I have compared the style of writing to all the French flute music 1701-1715, and the music here attributed to Marais is in a unique style. Perhaps it comes closest to La Barre, a flutist Marais worked with on a regular basis. (But I am certain the music is not by La Barre.)

A large chunk of evidence of Marais’s authorship is that the spine of the book lists Marais at the very top, over the more famous flute composer La Barre and the lesser names of “Folio, Gautier, and others.”

The incredible painting by André Bouys (1656–1740) pictures the main contributors to my flute volume. Seated on the left, with the gamba, we see Marin Marais. On the right, with the ivory flute, is Jacques-Martin Hotteterre. Next to him, standing, is Michel de La Barre opening a book of his own trio sonatas. In the middle is thought to be one of the Philidors, either François or Pierre. The standing figure at the far left is unknown, although some have speculated that it is Jean-Baptiste Lully (in spirit) looking over his musical followers. It is estimated that this painting was created in 1710 which, not incidentally, is also the year I would estimate for the Marais flute pieces.

I think it’s fair to call these previously unknown Marais pieces the biggest discovery in the flute repertoire since the Telemann duets (TWV40: 141-149) that were found in 1999 in Ukraine and returned to the Berliner Sing-Akademie collection, where they had been housed until being looted during the Second World War.

Scrounging for material

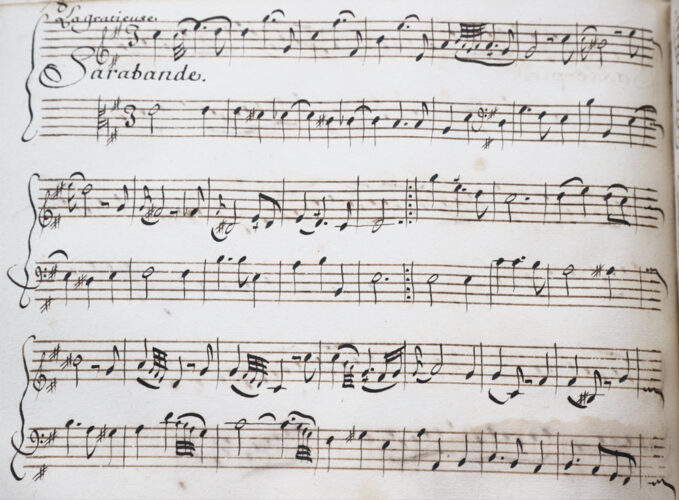

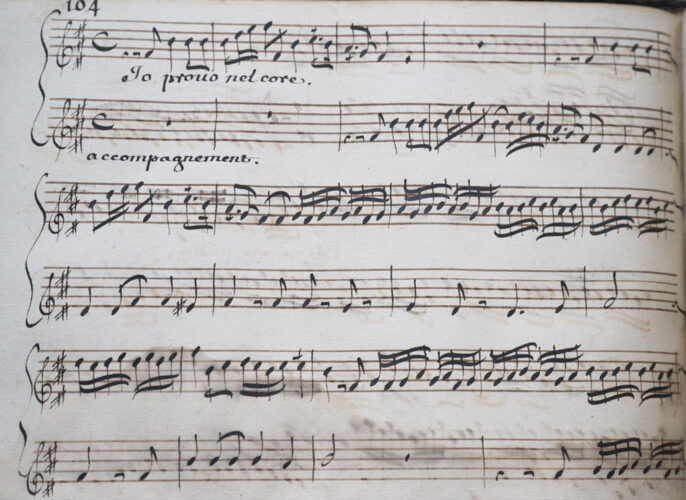

This is the first half of the Sarabande “La gratieuse”:

The ornamentation of the flute line is very expressive and is especially complex when combined with the bass line. Rather than using a large vocabulary of symbols placed on individual notes, as was common with ornamentation for viol, lute, or keyboard, Marais writes out his ornamentation and uses just a “+” to designate a trill of some type. Both the top line and the bass are reminiscent of his viol music. The flute line is written in French violin clef, with G on the bottom line, as was typical at the time. This was done to avoid ledger lines — for the flute, it gave one ledger line to low D and one ledger line to third-octave D and covered the basic range of the flute at the time. The bass part is primarily written in bass clef but, as we see at the beginning of “La gratieuse,” alto clef is used to avoid ledger lines when the range is high.

With the printed music in this volume dating from 1707-1711, it would have been played on a three-joint flute in the style developed by the Hotteterre family. These early Baroque flutes, as made by Hotteterre or Pierre Naust, are always at a very low pitch by comparison with today.

Three Baroque flutes, from top: Naust, Paris c. 1710, an early 4 joint flute, copy by Boaz Berney, A=400; Hotteterre, Paris, a 3 joint flute, copy by Rod Cameron, A=392; Pierre Naust, Paris, a 3 joint flute, copy by Rod Cameron, A=386 (Photo by Michael Lynn)

The organization of the Marais manuscript is also quite interesting. Although most of the movements are for flute and bass, there are also small sets of pieces for two flutes inserted between groups of movements for flute and bass. (The idea of alternating between pieces with bass and duos is not so unusual. Some years later, Pierre Philidor published three volumes of music where the suites alternate between flute and bass and flute duos.)

In these 70 discovered Marais pieces, there are 12 short duo movements inserted as four sections between the flute and bass sections:

Section 1 Flute and Bass

#1–18 – 18 movements

Section 2 Duo

#19-21 – 3 movements

Section 3 Flute and Bass

#22–31 – 10 movements

Section 4 Duo

#32 only – 1 movements

Section 5 Flute and Bass

#33-61 – 28 movements

Section 6 Duo

#62–63 – 2 movements

Section 7 Flute and Bass

#64 – 1 movement

Section 8 Duo

#65–70 – 6 movements

Figured bass costs money

It’s fun to speculate on how the collection of Marais flute pieces might have been entered into this large flute volume. Clearly, the person who had this book created, or the musician it was intended for, was an early adopter of the flûte traversière and certainly could have been an acquaintance of some of the composers in the volume. The owner would most likely have been a wealthy gentleman: This quantity of printed music, with a professional copyist and binding, would have been very expensive. (A female transverse flutist, at this early date, would be unlikely in my opinion. By conventions of the time, women were much more likely to play the viola da gamba and the harpsichord.)

After examining how the book is put together, I would conjecture that the owner hired the copyist to provide exactly 120 pages of flute music by Marin Marais. One of the reasons, I think, is that the manuscript also contains a section of Fanfares Pour deux fluttes allemandes of 26 pages, followed by a title page for Fanfares Nouvelles Pour deux fluttes traversiere ou deux hautbois with five lined (but blank) pages, which shows that the planning of pages took place before the entry of the music.

I would also guess that the copyist fee for the Marais section would have been more expensive if they had added the figured bass, assuming it was contained in the sources being copied. Where the copyist got the source material is another important question. I suppose he — most copyists at the time were men — could have obtained permission from Marais to access some of the composer’s own manuscripts, or perhaps the copyist had to use several different sources to get up to the required number of pages.

Looking at the layout of the volume, however, I think the copyist was scrounging for material by the end. There’s one rather simple Prelude as Section 7, and at the end, Section 8, the duets seem rather dissimilar to one another, with two of them being in a different style — not dance movements — from the rest of the manuscript.

As is often the case with large books with blank staff pages leftover at the end, this one contains little popular pieces from the time, such as le Carillon de Dunkerque or La Pierre fitoise. These are written in a much less professional hand when compared to the Marais and Foliot sections.

As these newly discovered works for the flute are of considerable historical value, as well as being superb additions to the rarified repertoire of early French flute music, I am working on making this music available to a wider public. The complete modern edition of the Marais manuscript will be published by Alry Publications in the same form as the manuscript, for just flute and bass. I also plan to publish the duet movements in an edition for recorders and flutes, both in the same volume. (A detailed listing of this rare manuscript was recently published by The Flutist Quarterly.)

This is elegant music written at a very special time and place. It is exciting for me to be able to present this outstanding new repertoire to today’s flutists.

Michael Lynn has served as professor of historical flutes and recorder at Oberlin Conservatory for the past 47 years. He has performed more than a thousand concerts with ensemble throughout the U.S. and has lectured and performed in Europe. www.originalflutes.com