Byzantine chant treats the voice as a fretless instrument. Its cultural roots place it at a unique intersection of historically informed performance and global music.

‘We knew not if we were in heaven or on earth’

This article was first published in the May 2024 issue of EMAg, the Magazine of Early Music America.

The sacred vocal music of the Christian East has made substantial inroads into the Western choral canon since Robert Shaw’s seminal 1989 recording of Rachmaninoff’s All-Night Vigil. Performing editions with detailed transliterations, diction guides, and notes have helped eliminate the obstacle of Church Slavonic’s linguistic unfamiliarity and helped advise performers on the detailed liturgical context of Eastern Orthodoxy. With such editions available alongside easily accessed reference recordings, Western vocal ensembles have widely incorporated into their repertoire the lush, expansive choral harmonies of Rachmaninoff, Gretchaninoff, and others — gaining widespread acclaim and winning Grammy Awards along the way.

Slavic choral music’s older, Eastern Mediterranean cousin — and the Syro-Greek sibling of the West’s own treasury of Gregorian chant — is Byzantine chant, also known as “the psaltic art” (Greek: i psaltikí téchni or psalmodía). This historic sacred repertoire is predominantly monophonic, accompanied by a drone, and employs a plethora of modes and tunings that treat the voice as a fretless instrument.

The wide variety of textures range from uptempo, simple, and syllabic tropária (single-stanza hymns) and psalmody, to papadiká, slower compositions accompanying high liturgical moments such as the Offertory and Communion, ornamented with great specificity, and melismatic in ways of which Baroque composers could only have dreamed.

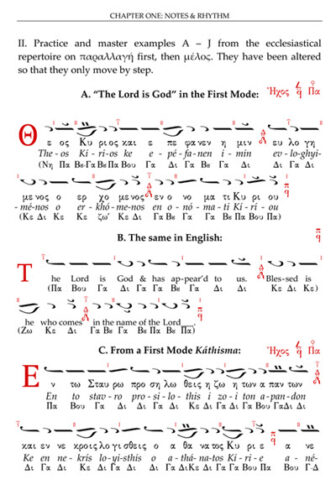

Byzantine music’s distinctive neumatic notation, with manuscript evidence reaching back more than a millennium, remains the idiom’s standard. The Greek idiom has enjoyed an unbroken performance tradition of 17 centuries that endures into our own day, and cantors and composers express the living tradition in Church Slavonic, Arabic, Romanian, Georgian, Turkish, English, Spanish, and more.

Byzantine chant’s historic and cultural roots, combined with the present-day creative vitality of its practitioners and composers, place it at a unique intersection of historically informed music performance and global music.

The very richness of Byzantine music, however, has challenged Western performers and audiences — even those accustomed to the esoterica of historically informed performance practice. In contrast, Russian choral harmonies were adopted with relative ease thanks to widely available transliterations. Also, tensions of “objective inevitably” have arisen. Historically informed ensembles seek to bring to life the music of another time and place for listeners in the present day; cantors that bring to life Byzantine chant’s characteristic extensive melismas and filigreed ornaments as their standard repertoire serve a different purpose. They seek to transport worshipers, not to the foreign country of the past, but to a reality utterly unconcerned with historical time and place. “We knew not if we were in heaven or on earth,” as the 10th century Prince Volodýmyr of Kýiv’s envoys to Constantinople described hearing the chanting in Hagia Sophia’s magnificent acoustics.

Western scholarship adopted an “Orientalizing” framework toward Byzantine music in the early 20th century. Fr. Adrian Fortescue’s infamous polemic description of Byzantine music in his 1907 book The Orthodox Eastern Church is a standard-bearer of such narratives. One of his milder assertions is that to “Western ears this music certainly sounds very strange and barbarous.” Other critics commonly argued that Byzantine chant in its received form was clearly a product of Ottoman occupation, and as such, manuscripts from after the 1453 fall of Constantinople could not be understood as representing “real” Byzantine music in any meaningful sense.

Beyond that, Western scholars argued over how much continuity with the past the neumatic notation represented, since the division of the octave into 72 tuning units and the multiplicity of modes were all but incomprehensible and alien to listeners conditioned by Bach and Mozart and Mendelssohn. For compositions found in the pre-1453 manuscripts, the preferred solution was to “normalize” it according to the Gregorian chant traditions at Solesmes Abbey, a Benedictine monastery in France, where the style includes an omission of the drone, “free” rhythm, a dry-voiced vocal quality, and Western diatonic tuning.

To be sure, a more nuanced understanding of Byzantine chant has been challenging to achieve.

There are many obstacles, including a lack of materials and teachers familiar with the idiom, Greek as the predominant language for performance, neumatic notation, tuning system, modal theory, and more. The relationship between the witness of the manuscript tradition and contemporary practice further served to confuse the issue.

Western scholars such as H. J. Tillyard, Egon Wellesz, and Carsten Høeg took pioneering steps toward dismantling such barriers with the founding of Monumenta Musicae Byzantinae (MMB) at the University of Copenhagen in 1931. Even so, the MMB produced transcriptions and recordings that reflected this anachronistic imposition of 19th-century Gregorian norms, assuming a fundamental and necessary rupture between modern practice and the older materials.

Historical performance a foothold

Ethnomusicology, on the other hand, planted the seeds for a different approach to Byzantine chant. For example, Laura Boulton made extensive field recordings of liturgical music throughout the Orthodox world in the 1950s and 1960s, including recordings of Holy Week at the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople (Istanbul), the epicenter of the Greek Orthodox world since Emperor Constantine moved the imperial capital to the city in 330 C.E.In her 1969 memoir The Music Hunter, Boulton drew a clear distinction between her approach and that of earlier scholars:

“Musicologists today often have a struggle to locate the genuine article; the end product is so influenced by ‘civilization,’ that only keen research reveals how much is worth collecting at all…certainly the so-called authorities in their learned volumes often differ widely in their facts…and particularly in their interpretations. I have for the most part written of my own observations…“

Boulton’s approach allowed her to encounter Byzantine chant in its own context and on its own terms without presuppositions about what it “should” sound like. Consider her account of the Easter service at the Ecumenical Patriarchate:

“It is difficult to describe the majesty, joy, and beauty of that Easter service… The realization struck me that, after centuries of struggle under Turkish rule, the greatest triumph of the Patriarchate is that it survived at all… They sang with devotion and fervor the melodies passed on and preserved from the early Church with no thought of adding anything original, individual, or spectacular.“

Rather than denigrating the “strange and barbarous” technical differences, Boulton focused on Byzantine chant as the expression of joy and faith for the worshiping community, and was thus able to perceive, and convey, its beauty.

The emergence of historically informed performance practice created an opening within which Byzantine chant could establish a foothold. This development was concurrent with the growing popularity of “world” or global music in the West, as well as new flourishing of “traditional” music in Greece which encompassed Byzantine chant as well as Hellenic folk music.

Thus the European early-music circuit of the 1970s and 1980s frequently hosted ensembles such as Lycoúrgos Angelópoulos’ Greek Byzantine Choir, appearing at the English Bach Festival and elsewhere. Their appearances on the continent drew the attention of French musicologist and choral conductor Marcel Pérès, leading to a years-long collaboration on early Roman chant manuscripts. Where the MMB, starting in the 1930s, sought to apply a Gregorian filter to Byzantine chant, Pérès and Angelópoulos came from the other direction: They considered how Byzantine performance practice could inform the performance of these older Western repertoires.

Pérès’s Ensemble Organum and Angelópoulos produced several recordings around this concept, beginning with the seminal 1986 release Chants de l’Église de Rome des VIIe et VIIIe siècles: période byzantine. In addition, Gregórios Státhes’s choir Maïstores tis Psaltikís Téchnis (“Masters of the Psaltic Art”), founded in 1983, appeared at international venues such as the Sydney Opera House and Saint Mark’s Basilica in Venice.

The world-music scene in continental Europe saw the Theódoros Vassilikós Ensemble collaborate with the Ocora label of Radio France on a series of recordings based on live concerts, including releases such as Grèce: Liturgies anciennes orthodoxes – Chants sacrés de la tradition byzantine, from 1979. That same year, Deutsche Grammophon released a series of live recordings of Holy Week at the monastery of Xenophóntos on Mount Athos.

Despite these advances in the U.K. and continental Europe, obstacles persisted on the other side of the Atlantic. Greek Orthodox diaspora communities in the U.S. had embraced a program of musical acculturation throughout the 1960s and 1970s, with Byzantine chant largely eschewed in favor of polyphonic choral music with organ accompaniment.

While interest in the medieval repertoire was relatively well represented in Anglo-American musicology, the American Musicological Society did not host a panel on Byzantine music until Jessica Suchy-Pilalis organized the first such panel for AMS’s 1990 conference.

‘Beautiful voice’ genre

Western scholarship began to reconsider many of the earlier generation’s assumptions. In 1998, in his monograph The Sound of Medieval Song: Ornamentation and Vocal Style According to the Treatises, Timothy J. McGee concluded that medieval European vocal styles shared the tuning systems and ornamentation of Byzantine music, and that this represented an overall “Roman singing style.” In a 2003 conference paper, musicologist and choral conductor Alexander Lingas, founder of Cappella Romana, wrote that Byzantine chant’s modern performance practice represented a “continuous tradition reaching back into the Middle Ages.”

With David Hiley’s persuasive arguments in his 2009 book, Gregorian Chant, that Solesmes “was in effect a new creation… [and] no memory persisted of how medieval [Gregorian] chant was performed,” the anachronism of trying to understand Byzantine music through the framework of Solesmes was put to rest. The repertoire could be allowed to stand on its own.

In recent years, wider mainstream interest in Byzantine chant on its own terms has emerged. A common programming concept is an East-West “encounter”; for example, in 2016 and 2017, Panagiótis Neochorítis, árchon protopsáltis (“chief precentor”) of of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, collaborated with renowned Catalan early-music star Jordi Savall on the program The Millenarian Venice: Gateway to the East. This was promoted as an “intriguing musical tour through the 1,000-year history of the Venetian Republic and its far-flung territories,” ranging “from the Medieval to the Baroque from around the Mediterranean rim” and including “the eras of the Byzantine and Ottoman empires.”

Savall’s program presented Neochorítis and his choir to international audiences at early-music festivals such as Utrecht, as well as major Western concert venues such as Carnegie Hall. Neochorítis’ schola performed a number of historic monuments of the repertoire, including Pásan tin elpída mou (“All my hope”) by Pétros Berekétes (1665?-1725?) and Tin déisín mou (“My supplication”) by Geórgios of Crete (fl. ca. 1790-1816), both belonging to the highly melismatic kalophonic “beautiful voice” genre (unrelated to the Italian bel canto).

“All my hope,” for example, is a plaintive cri de coeur in supplication of the Virgin Mary. With extremes of range and ornamentation, and a tempo reflecting a near-total pause of earthly time, this chant gives the virtuoso soloist a broad canvas for vocal expression and the freedom to stretch out the text to seemingly impossible lengths. Also included is Géfsasthe ke ídete óti christós o kýrios (“Taste and see that the Lord is good”), a virtuosic choral Communion chant by Ioánnis Kladás (fl. 1400). The Millenarian Venice was well enough received to justify a commercial recording that was released in 2018 on the Alia Vox label.

In 2023, Western public exposure to Byzantine music reached a new height: Buckingham Palace announced that, at the request of King Charles III, Capella Romana conductor Alexander Lingas would direct a Byzantine chant ensemble for the coronation service at Westminster Abbey in recognition of the new king’s father, Prince Philip, who was raised in the Greek royal family. During the Exchange of the Swords, Lingas led a choir of seven cantors in a setting of Psalm 71 composed specifically for use in royal ceremonies. Millions worldwide saw Lingas’ performance on broadcast and digital media, and it drew acclaim for its beauty and solemnity.

U.S.-based Cappella Romana has been at the forefront of bringing Byzantine music to life for American and international audiences. In February 2020, NPR profiled the ensemble’s Lost Voices of Hagia Sophia project, drawing interest to Byzantine chant and the Constantinopolitan cathedral tradition amid growing international concern over Hagia Sophia’s future as a museum. NPR’s feature transformed Lost Voices into a mainstream commercial success, and it finished 2020 as the number-two album of the year in the Billboard Traditional Classical Albums chart.

In addition to performing and recording, Cappella Romana has most recently taken on publishing as the next step in making Byzantine music accessible to the Western mainstream. This effort is driven in part by the duty they feel to make their source materials available for other ensembles and performers.

“In many cases, we’re performing works that haven’t been sung in centuries,” Lingas says. “We’ve got filing cabinets full of manuscript transcriptions that have been produced for us over the decades by the premier experts in the field, along with the supporting research. We have an obligation to find a way to make these materials usable and accessible, and publishing is a logical way to do that.”

Cappella Romana Publishing’s first offering, in 2023, was a comprehensive English-language manual on Byzantine chant notation and theory: Byzantine Chant, The Received Tradition: A Lesson Book by John Michael Boyer. At the end of 2023, Cappella Romana Publishing also released Kassianí: Christmas Vespers, a set of the medieval works of the ninth-century Constantinopolitan nun Kassia, the oldest woman composer for whom we have music, published specifically for the secular performer and researcher.

Following Lingas’ participation in the British coronation, the organization also contributed a bi-notational score of Psalm 71 to Novello’s commemorative publication of the Order of Service. Future possibilities for historically informed performance ensembles include an anthology of scores from Hagia Sophia, more Kassianí, and manuscript transcriptions from the Byzantine monastery of Grottaferrata, outside of Rome. “With any luck,” says Cappella Romana’s Executive Director Mark Powell, “the next time there’s a Byzantine chant performance at Carnegie Hall, an interested audience member will be able to order the scores on Amazon.”

Mainstream American audiences perhaps have yet to have their own “heaven on earth” moment with Byzantine music, as Prince Volodýmyr’s envoys did when they visited Hagia Sophia. All the same, the combined efforts of the early-music community over the last few decades appear to be making a new Robert-Shaw-in-1989 moment inevitable. “We’re committed to doing more than offering ephemeral revivals and the occasional recording by just one ensemble,” Lingas says. “We want to make it available to everybody who wants to take it on.”

Richard Barrett co-hosts the podcast A Sacrifice of Praise: The Living Tradition of Byzantine Music in America and sings regularly with ensembles such as Cappella Romana and Psaltikon. He is also a freelance writer, the director of publications for Cappella Romana, and the protopsaltis and Director of Music for Dormition of the Virgin Mary Greek Orthodox Church in Somerville, Mass.