The ‘you-decide’ ticketing model comes with high hopes but inconclusive results

‘Research suggests that it’s artistic content, not tweaks to the ticketing model, that drives attendance and diversity’

This article first appeared in the January 2024 issue of EMAg.

It boils down to one basic and highly unsatisfying rule: When it comes to ticket pricing, there is no rule.

That’s a finding of Indiana University’s Michael Rushton, an economist whose research areas include cultural policy, arts administration, and nonprofit management and philanthropy, summarized in his 2014 book Strategic Pricing for the Arts.

In a recent conversation, Rushton explains that “the only way that you can really learn about consumer demand is by conducting little experiments.”

In the 2023-2024 season, two of the most established early-music presenters in the U.S. are running their own big experiments by adopting some form of a pay-what-you-can ticketing model — attempting to balance the need to stop a decline in attendance, attract audiences that reflect the diversity of the communities they serve, and, not least, increase box-office revenue and donations over time.

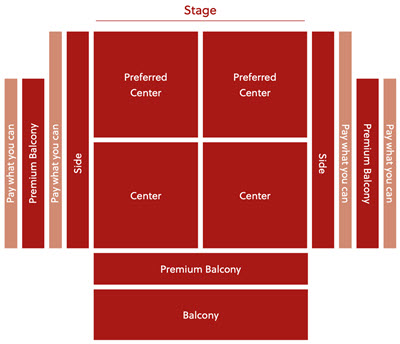

In past seasons, New York’s Music Before 1800 and the San Francisco Early Music Society followed an age-old format: subscription packages, individual tickets at a range of fixed prices, and discounts for select groups, such as students. This season, Music Before 1800 (MB1800) is still offering subscriptions and individual tickets at fixed prices (ranging from $35-$60), but they have also set aside pay-what-you-can seats in their long-time venue, Manhattan’s Corpus Christi Church. A patron may purchase one of these seats online in advance for $10 or at the door at any price.

MB1800 Executive Director Bill Barclay estimates that 50-100 seats will consistently be made available for pay-what-you-can. Box office can fluctuate depending on the show, but MB1800 generally aims to sell upward of 300 seats per concert at their 450-seat venue. Barclay sees any empty seat as a “missed opportunity to share the healing power of live music in community” and hopes their pay-what-you-can option will make attendance accessible to anyone.

With an annual budget around $300,000, MB1800’s pre-pandemic box office accounted for more than 40 percent of its income. Now, it’s closer to just a quarter of total revenue. As Barclay said just ahead of the season opener, “We’re not simply going to get that audience back. We have to get new people in.”

On the other side of the continent, taking this pricing model a step further, all tickets to individual San Francisco Early Music Society (SFEMS) concerts are now available on a pay-what-you-can basis. Concert-goers who purchase a ticket on the SFEMS website have the unusual experience of typing a value of their choice into a box marked “Price.”

SFEMS provides the following context for ticket-buyers: “Last year, individual tickets were $55–$65. For this year, we suggest a ticket price between $30 and $40 per ticket. That said, anything is appreciated and if you can pay more, please do!”

Before the pandemic, earned income (which includes ticket sales) made up about two-thirds of SFEMS’ revenue. During the pandemic, that figure dropped to 50 percent. The risks of SFEMS’ radical departure from standard ticketing might be mitigated by season subscriptions. Subscribers are the only audience members with an assigned seat. When purchasing their subscription, patrons are also asked if they would like to contribute to the organization’s Pay it Forward Concert Fund, designed to sustain the pay-what-you-can model. Executive Director Derek Tam estimates that about 40 percent of SFEMS’ 160 or so subscribers have elected to “pay it forward,” in varying amounts and reports that while some of these donors have given amounts in the “high four digits,” there is also a base of many small donors.

This level of generosity wasn’t a surprise to Tam and SFEMS board members who, in part, were willing to take this leap of faith after seeing how long-time subscribers had really stepped up their financial contributions to shepherd the organization through COVID and its aftermath. “Because of this, we knew that there was likely a basis for additional support for a large effort like pay-what-you-can,” says Tam. (Full disclosure: Tam currently serves as EMA’s board president.)

SFEMS concerts take place in three rather large spaces — in San Francisco, Berkeley, and Palo Alto — and the organization has typically counted on filling a third of the seats. Tam hopes that by eliminating cost as a barrier, Bay Area residents unfamiliar with early music might be willing to give it a try: “Among many things, finances are a really important part of creating accessibility and giving people an opportunity to try early music very easily.”

Around the country, a growing number of arts groups ranging from Boston Ballet to Seattle Opera, from Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre to New York City’s Lincoln Center, are experimenting with some form of pay-what-you-can. Many of these venerable institutions are struggling to attract and retain audiences and with parallel difficulties in fund-raising.

But as history has proven, times of great challenge breed great innovation. Acknowledging the reality that many audience members fell out of the concert-going habit during the pandemic, Tam and the SFEMS board were motivated to take action: “We surveyed the SFEMS community and found that cost was one of the top reasons people weren’t coming back, besides COVID and health. We couldn’t solve for health and COVID issues, but we could at least acknowledge the ticketing issue.

“It seemed unlikely that a certain segment of our audience was coming back,” Tam continues, “so it was important to figure out who the next audience would be.”

Price vs. perceived value

Following the murder of George Floyd and the increased visibility of the Black Lives Matter movement, many arts organizations have felt an urgent obligation to better serve and reflect the diversity of their local communities. Many see pay-what-you-can as one way to address this newly prioritized mission.

In Minneapolis, where Floyd lived and died, the American Composers Forum (ACF) transitioned away from its long-standing model as a membership organization. At the height of the pandemic, the ACF decided to waive the $70 membership fee with the rationale to better serve its community. As the pandemic started to wane, the ACF chose not to return to its membership structure. Instead, anyone can access its resources at no cost.

ACF Director Vanessa Rose credits the Community Centric Fundraising movement as her organization’s guiding light. A BIPOC-led movement that began in Seattle, Community Centric Fundraising describes itself as “a fundraising model grounded in equity and social justice,” where an organization’s mission isn’t as important as the collective community. And the collective community takes precedence over a nonprofit’s donors: “We respect donors and build strong relationships with them, but one that they are not the center of.”

Rather than incentivizing membership through benefits, its spectrum of users — composers, administrators, ensembles, adjacent artists, new-music fans, philanthropists — are encouraged to make a donation of any size to sustain the organization.

A fundraising model ‘grounded in equity and social justice’ where an organization’s mission isn’t as important as the collective community

While a few organizations across the country are in the early stages of their pay-what-you-can experiments, many already find reason for hope. Rose speaks cautiously of a “steady pace” in AFC contributions, a cause for “optimism about growth over time.” Barclay reports the attendance at MB1800’s season opener exceeded expectations, including about 20 audience members who took advantage of the pay-what-you-can option. And Tam saw a surprisingly high number of new faces at SFEMS’ season opener, including more children than he recalls ever seeing before.

These positive impressions aside, economist Rushton cautions organizations considering ticketing experiments to weigh the potential economic pros and cons: “There’s no point in having an empty seat. If someone can only pay $2, that’s $2 more than you had before. You might have new customers who weren’t willing or able to pay regular price and some who pay more.”

On the other hand, Rushton continues, “the concern is that if people pay more than they used to at a concert, they might be less generous when it comes time for donations. It might be that, in total, they’re actually going to give less than they would have if you had ordinary ticket sales and then a bit of a fundraiser campaign. For the people that do have money, you’re essentially combining tickets and donations.”

For the people with money, ‘you’re essentially combining tickets and donations’

Hannah Grannemann, director of the arts administration program at the University of North Carolina-Greensboro, also cautions arts organizations to consider the relationship between price and perceived value, especially when it comes to new audience members: “The impact of prices on consumers is complex, but there is a body of consumer behavior research that has shown that lower prices can have the effect of devaluing the perceived value of the arts event, or any product.

“Having low ticket prices can inadvertently send a message of low quality,” Grannemann continues. “This is especially true when a consumer doesn’t know much about the experience, product, or service. They rely on the thinking behind the saying ‘you get what you pay for’ to evaluate quality when they don’t have another way to evaluate quality.”

In the U.S., our capitalist value system puts the expensive and the rich on a pedestal, and popular shows often reflect that attitude. Consider ticket prices for events with high demand. The New York Times reports that, in 2022, the average ticket price paid for one of the top 100 tours in North America was $111, while the average Broadway ticket was $126. At the high end, news reports and social media feeds were abuzz about fans dropping thousands of dollars per seat to see megastars like Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, Bruce Springsteen, or Madonna.

‘It’s not just for the elite’

Yet for smaller, more nimble ensembles, the economics of pay-what-you-can have already proved sustainable. Scrag Mountain Music is a wide-ranging chamber ensemble in Vermont whose motto has always been “Come as you are. Pay what you can.” It has operated as a you-decide ticketed organization since 2010. Each season, Scrag Mountain Music (SMM) presents up to five chamber programs in rural communities, typically with three to six musicians per program. The co-artistic directors, soprano Mary Bonhag and bassist and composer Evan Premo, founded the ensemble with no paid staff. Audiences initially chipped in an average of $12-$13 per ticket.

Bonhag and Premo were committed to making concerts as financially accessible as possible. After a lawyer friend helped them incorporate, they wanted to continue with pay-as-you-can. “The board was skeptical because we couldn’t point to other examples,” says Bonhag. At the time, the closest analogy Bonhag and Premo found was church: “Anyone can go to a service and receive an offering. If you have money to give to the church, you do; if you don’t, you don’t. But it’s not a barrier to entry. We asked the board to give us a chance and said that if it didn’t work out, we’d do the standard ticketing thing.”

Today, its audience members spend on average $18-$20 per ticket. After several years of not taking a fee, Bonhag and Premo have been able to pay themselves something for the work they do as administrators. Like many performing arts organizations, the majority of SMM’s income comes from donations and grants, including successful annual appeals. Running and performing in the ensemble is not Bonhag or Premo’s only job but, over time, it has become a meaningful source of income. Bonhag credits their community for growing SMM and loves being able to bring live music to Vermont at quite literally any cost: “This music belongs to all of us. It’s not for the elite only. This payment model directly addressed this elitism.”

Fourteen years in, time has shown that pay-what-you-can is not a magic bullet. “We were initially naive to think that finances, venue choices, age, and even the way classical music is typically presented were the only barriers to this music being enjoyed by the general public,” says Bonhag. Despite their growth and local success, pay-what-you-can hasn’t made Scrag Mountain Music immune to the challenge of attracting new and broader audiences.

Is price really the obstacle?

Anecdotal and short-term assessments aside, it’s worth emphasizing that the impact of pay-what-you-can ticketing on classical music in general, and specifically early-music concert attendance and demographics, has yet to be studied in depth.

Based on past studies examining the relationship between price and museum attendance, economist Rushton expects that ensembles that adopt some form of pay-what-you-can will run into limitations: “One of the things we know about the arts, especially when it comes to what have traditionally been called the ‘high arts’ — art museums, classical music, early music, and so on — is that they are consumed on the whole by people who have higher levels of formal education. Level of education and income are often correlated, but actually the higher level of education matters more. A poor Ph.D. is more likely to go to the museum than a rich person without a degree.”

In recent years there have been major debates in the museum world over whether admission should be free. Rushton was among the scholars involved in seeking answers. “One thing I can say where there is research is that you’re not really going to bring in people on a tighter budget, even for the best of motives,” he says.

Grannemann cites research that comes to slightly different conclusions. “Studies generally show that pay-what-you-can and free admission can increase attendance but don’t have much impact on audience diversity. The same people who would come on a normal basis take the opportunity to come when it’s less expensive or free,” explains Grannemann, who has grappled with this dilemma herself as an arts administrator.

But classical and early music’s distance from the mainstream might also make certain limitations less surprising. According to Rushton, the percentage of the U.S. population that consumes classical music in any form (including YouTube and Spotify) is in the teens. That drops to single digits when you look at who attends live classical concerts. Low classical attendance “is something that comes from the culture rather than any individual organization. You can try to do outreach, and that’s great, but it takes an entire culture to really make a dent in that,” says Rushton.

The research on arts ticketing, affordability, and diversity is still a growing field. Empirically speaking, which variables might actually fill an otherwise empty seat at an early-music concert?

Some arts organizations have found that content, what you show or what you play, can make a difference, but ticket price is not the thing

At Southern Methodist University, Zannie Voss, who is also director of the National Center for Arts Research, co-authored a 2021 report aimed at answering the post-pandemic question, “When we re-open, whom will we gather?” Written in layman’s language, this open-access document identifies physical distance as a key variable for arts organizations to consider when trying to reach historically underserved communities.

The researchers found that “BIPOC households and households with income less than $50k are less likely to travel longer distances to performing arts venues than their counterparts.” To reach this conclusion, Voss and her co-authors drew from a 2018 study that used mobile data to demonstrate that within a city, people generally travel to areas where the socio-demographics match their own identity.

Voss recommends that “[an] organization consider whether it might offer programming in lower income neighborhoods at a low price before considering a pay-what-you-can at their regular venue.” However, as her study notes, this strategy is not without potential polarization pitfalls. One arts administrator, whose organization supports its DEI mission with educational programs in underserved areas, told the researchers: “We’ve had predominantly white audiences [in the home venue] and predominantly African Americans participating in our education programs…we’re working on things that will bring those audiences together.”

For all the experiments in tweaking ticket models, Rushton cites research demonstrating that artistic content is a more effective tool than price when it comes to attracting and maintaining more diverse audiences. Referring back to studies that look at museums, he explains that “what museums and some performing arts organizations have found is that what you show and what you play can make a difference, but ticket price is not the thing.”

Whether pay-what-you-can turns out to be the right fit for individual early-music presenters or ensembles remains to be seen. What’s already worth celebrating is that, when faced with big challenges, leaders in the field are open to thoughtful experimentation.

Ashley Mulcahy is a Boston-based mezzo-soprano and graduate of the Voxtet Program at the Yale School of Music and Institute of Sacred Music. She sings with numerous ensembles and co-directs her own voice and viol ensemble, Lyracle.