This MUSINGS column on public musicology was first published in the May, 2023, issue of EMAg, the Magazine of Early Music America

How do I know what I read is true? Can I trust the author? The first question is covered, in the realm of “scientific” writing, by peer review. It’s the careful documentation of sources by authors of papers, books, reports of a “scholarly” nature — the forest of footnotes. In humanistic writing it’s a bit like reproducibility in science, I suppose: You make your argument clear, and where you are proposing a solution that may not be the solution, you say so, indicating that it’s your interpretation of the evidence available — and in historical writing the evidence is never sufficient.

In fact, it seems to me that if there’s not some interpretation on the part of the scholar, it’s not really scholarship. That doesn’t make it useless — a lot of invaluable publications, such as lists, catalogues, transcriptions of court records, calendars of state papers, and bibliographies, attempt simply to report the facts as they survive. But even in these cases, it usually requires a lot of deep knowledge, careful preparation, expert technical skills, and almost always some interpretation (what was on the missing page of the ledger? what’s below that ink spot?) on the part of the transcriber or editor.

All of that scholarly work is the basis of almost everything we know about the past. But often we don’t want the whole encyclopedia thrown at us (in fact, the encyclopedia itself is usually a derivative effort, summarizing the work of scholars). How do we get the information we want? How do we keep up with what’s going on now? That’s where a kind of writing that is variously called criticism, musical journalism, public musicology, or haute vulgarisation, comes in.

What all these appellations have in common is that they are written to be read by non-experts. Given that we are all non-experts on most things, this is the kind of writing that we read most often: blogs, newspapers, various websites, journals, Facebook affinity groups, and on and on.

Various relationships are involved in these writings and readings. Some are peer-to-peer conversations (on social media forums, for example), where one person asks a question and a lot of people, often strangers, post their answers. Many are good answers; others are hopelessly off the mark. Some relationships involve an expert writing for an inexpert public. In the case of music reviews, the writer is both an experienced listener and a prose stylist whose opinions are widely interesting — although she may or may not be trained in scholarly aspects of music.

Other writing, of course, is designed to give the interested reader information: the life of Mozart, say, or program notes for the symphony. In these cases, a couple of issues may arise. Does the author really know this to be true? Can we trust the author? This is where reliable sources — like the magazine you’re reading (ahem) — can assure us that at least the editor and his staff believe this to be material worth reading.

And there are times when people trained in scholarship, and who regularly produce articles and books and editions full of footnotes and designed for other scholars, also write for a larger audience of interested but not necessarily expert readers. This is what is sometimes called “public musicology.” The late Richard Taruskin was a star in this field, as in so many others. His writing for a wider readership is beautifully composed, full of often venomous opinion, and delicious to read.

I myself have emerged occasionally from my medieval scholarly dungeon to write a bit for a broader audience.Mostly it’s because I find something so interesting that I want to share it, not dissect it. I have a little book called Early Music: A Very Short Introduction, and it was one of the hardest tasks I ever performed. It’s really hard to say a little about something you know (and care) a lot about.

I guess the main thing I take from musing about this topic is that informing people is really important, that entertaining them is equally important, and that being able to trust your author is the safest way to be informed. But at the end of the day, it’s all a matter of sharing one’s enthusiasms.

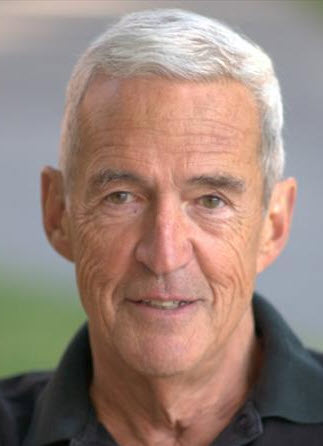

Thomas Forrest Kelly is Morton B. Knafel Professor of Music at Harvard, and previously directed early-music programs at Wellesley, the Five Colleges, and Oberlin. He is past president and a longtime board member of Early Music America and the author, most recently, of Melisma: Wordless Song in Medieval Chant (Oxford Univ. Press).