“Early music” gets revived anew every few generations. What can an earlier revival teach us about our revival’s method and aims?

Early music revivals come and go. Our revival, the one that gained traction in the post-WWII decades, has distinguished itself for its persistence — going strong after three quarters of a century! — and tendency to naval gaze. But it shares with all previous revivals a passion to enlist an imagined past to tell a modern story.

After all, if the past is a foreign country and they do things differently there, why else would we visit that remote land other than to reflect, ultimately, on the places we think of as “home.” Rather, I’d like to reflect here on early-music revivals as a basic feature of Western musical culture, and to consider how the persistent revivalism of our music-making might help us better understand the current moment of the revival du jour.

At stake is the fact that this current cultural moment is increasingly incompatible with values and practices that are baked into the post-WWII early-music revivalism.

Recent incremental efforts to increase the diversity of early music’s repertoires and participants (performers, researchers, and audiences) are important. But, overall, the way we think about “early music” remains grounded in mid-20th-century binaries. If revivalists of the 1960s and ’70s saw in early music alternatives to the institutions of Romantic high culture, it would take another couple decades for the revival to acknowledge that categories like “Europe” or “concert” themselves have alternatives that warrant attention.

The systems of patronage, higher education, and commerce that largely support today’s “early music” remain decidedly 20th century, and it is possible that these systems are responsible for some of the inequalities that persist in our industry. Increasing the diversity of the repertoire and those that play it is important. But the conditions and ideologies of the revival itself may be resistant to the deep changes called for by the climate crises, corrosive populism, and other manifestations of late capitalism.

About a century before our current early-music revival was starting to hit its stride, a newspaper notice for a “Colored Old Folks’ Concert” appeared in Connecticut’s Middletown Constitution of Wednesday, May 7, 1862. Typically, “Old Folks” concerts were not associated with performers and audiences of a particular group or identity, but the newspaper announcement seemed to make a point of communicating the race of these musicians: “If our citizens want to hear some old-fashioned music by people who know how to sing, and want to see some ancient costume, they can do it on Thursday night,” the notice read.

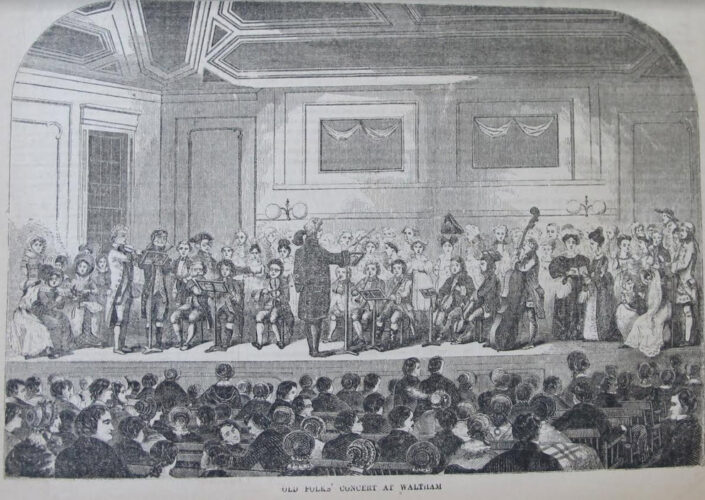

In his article “‘Old Folks’ Singing and Utopia: How Abolitionist Musical Antiquarianism and Calvinist Eschatology Gave Birth to Science Fiction on the Banks of the Connecticut River,” ethnomusicologist Tim Eriksen tells the story of this remarkable Civil War-era early-music revival. Eriksen describes how several dozen Black members of Hartford’s Methodist Episcopal Zion and Talcott Street Congregational churches traveled to Middletown to perform before a large, ethnically diverse audience at the thousand plus-capacity McDonough Opera House. Like other choirs that participated in Old Folks revivalism, the Hartford singers’ music was drawn from the heyday of New England’s earliest native-born composers, roughly 1770 to 1810, a group that included William Billings, the first to publish a book entirely composed of his own compositions.

Eriksen writes, “unlike the more restrained music heard in most area churches at midcentury, the old folks’ music, often sung ‘with the speed of darting cavalry,’ had a sense of abandon, a groove, and a tumbling melodic drive that Harriet Beecher Stowe likened to an ‘ocean aroused by stormy winds, when deep calleth unto deep in tempestuous confusion.’” For nearly half a century leading up to the Old Folks revival, the music of Billings and his contemporaries had been maligned by reformers and shunned from church services. Now however, during the Civil War, Black singers were dressing up in New England Colonial costumes and reviving a repertoire that celebrated liberty and self-determination.

But the Old Folks Concerts, which entailed costuming and mobilizing lost ways of singing to perform forgotten (sometimes repudiated) repertoires, is comparatively similar to the post-WWII revival, which has more than flirted with costumes and remains enamored of performance practice.

Stranger still might be the revivalism of fin-de-siècle France, in which surviving historical instruments were used with little regard to original performance practices to perform music composed “in the style of” revered composers of centuries past. The Société des Instruments Anciens, for example, founded in Paris in 1901 by Camille Saint Saëns and Henri Casadesus, toured Europe, the U.S., and Asia to great acclaim during the first decades of the 20th century. The historical instruments they played — including quinton, viola d’amore, viola da gamba, hurdy gurdy, and harpsichord — never actually played together in their natural habitats of the 17th and 18th centuries, and the ensemble’s repertoire was often surreptitiously composed by its members. Three of these spurious works, like 18th-century cuckoo’s eggs, enjoyed widespread success until recent decades: the Adelaïde Violin Concerto in D (ascribed to Mozart), a cello concerto in C minor (J.C. Bach), and a viola concerto in B minor (Handel).

While our modern instinct is to simply dismiss these works as frauds (as we might the spurious “historical” musical instruments produced by the roughly contemporaneous Leopoldo Franciolini), I think this instinct might reveal something about our own revivalist priorities. The musicians of the Société were not interested in historical performance practice — they cut the surviving frets off of their instruments and worked to make them sound as loud and lush as their Romantic counterparts — nor were they interested in fidelity to earlier repertoires or aesthetics. Their revivalism, in other words, was diametrically opposed to the research-based authenticism that continues to guide today’s revivalists.

I’m not suggesting that these older revivals somehow hold the key to revitalizing our revival, and revivalism can, of course, be bent to serve unsavory ends. In the 1920s, Henry Ford’s so-called Old-Time Dance Orchestra, for example, revived earlier instruments and performance practices in the service of an imagined white Protestant America untroubled by Jews, immigrants, or Black people. Rather, early-music revivals seem to be a recurrent fact of Western musical culture. Their varied approaches, sounds, and failures can help us see both what is distinctive about our current revivalism, as well as the opportunities we may have to create a revival that speaks to our current moment.

Loren Ludwig is a viol player and music researcher based in Baltimore. He holds a B.Mus. from Oberlin Conservatory and a Ph.D. in musicology from the University of Virginia. He blogs at lorenludwig.com.