Sawney Freeman’s the Musicians Pocket Companion may be the earliest published music by a Black composer in the United States

An 1801 newspaper advertisement, a lost publication, and a hand-written copy book

This article was first published in the January 2025 issue of EMAg, the Magazine of Early Music America

When you think of slavery in the United States, the Northern states may not come to mind. However, the enslavement of Africans had a long history in New England before the Civil War. Equally long is the history of enslaved and free Black people in the U.S. making music.

The great majority of early Black American music was unwritten, with instrumental styles, songs, and performance practices passed from one generation to the next through oral traditions. The Western notion of “composer” has been an enduring, racialized category. As explored by Mary Caton Lingold and other scholars, this seemingly basic concept requires rethinking to account for music-making by people of color and from diverse cultures.

Nevertheless, for some time, African American composers have been understood as active participants in American composition. The Library of Congress currently lists Francis Johnson’s A Collection of New Cotillions (Philadelphia, 1818) as the earliest printed music by an African-American composer. Even earlier was Occramer Marycoo, known as Newport Gardner, who may have composed the song “Crooked Shanks,” published in A Number of Original Airs, Duetto’s and Trio’s [sic] (Massachusetts, 1803). (Occramer Marycoo was the subject of an online EMA article in June 2023.)

A few years ago, when members of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Essex, Conn., were investigating their town’s historical ties to slavery, they uncovered the story of a musician who was born into slavery and later became free. Sawney Freeman’s the Musicians Pocket Companion, advertised for sale in 1801, now seems to be the earliest known publication by a Black composer in the United States.

The earliest reference to Sawney Freeman can be found in an estate inventory from 1777. A boy named Sawn is one of two children listed as the “property” of Samuel Selden, a major landowner in Lyme, Conn., and a colonel in the Revolutionary War.

Slaveholders often rented out the enslaved to earn extra income for themselves, and that seems to have been the case with Sawney. His next documented appearance is in a 1790 newspaper advertisement in the Connecticut Gazette.

It wasn’t Seldon but Elisha Lay and Stephen Johnson offering a reward for the return of “two fellows, one white and the other black” who had run away. The notice reads, “The black fellow named SAWN, about 22 years old, about 5 feet 6 inches high, thick set, is a fiddler, and carried a fiddle with him.” It goes on to say, “Whoever will take up and return said fellows, shall have five dollars reward for the white, and ten for the black boy.”

Such advertisements were not uncommon, and, collectively, they tell us a great deal about Black musicianship. Musicologist Robert B. Winans sifted through hundreds of advertisements demanding and offering monetary rewards for the forcible return of runaways.

In his essay “Black Musicians in Eighteenth-Century America: Evidence from Slave Advertisements,” published in the 2018 volume Banjo Roots and Branches, Winans presented evidence of 370 Black runaway musicians from the North and 390 in the South in the 18th century.

In Connecticut alone, Winans identified 64 runaway Black musicians, representing approximately 1/8 of the runaways whose escape was advertised in newspapers. Similar advertisements, published in England that identify runaways with their musical instruments, show that this was an international phenomenon.

At first glance, it might seem surprising that runaway slaves would take their musical instruments with them. After all, they were escaping under the most dangerous circumstances and surely knew that they would be pursued. Fiddles are fragile, somewhat bulky, and relatively difficult to carry around. In addition, as the advertisement in the Connecticut Gazette shows, runaways carrying instruments were more easily identifiable. Why go to all this trouble for a fiddle?

Celebrations in the Black Community

This extremely perilous situation highlights just how important Sawney’s instrument was to him. To be sure, Sawney may have had practical reasons to flee with his fiddle: He may have needed it to earn a living. But the fact that so many runaways brought their instruments with them suggests that something more was at stake. As for most musicians, their musical instruments have afforded them a vehicle for autonomy, self-expression, solace, and celebration, and were thus central to who they were.

Sawney was evidently recaptured and returned to the Selden family. However, by the early 1790s, abolitionism was spreading through Connecticut. In 1784, the state passed a Gradual Emancipation law. It did not immediately abolish slavery, but rather allowed for the phasing out of slavery over time.

The law and its implications may have been a factor in the Selden family’s decision to emancipate Sawney in 1793. Slavery persisted in Connecticut, finally ending in 1848. Sawney took the last name Freeman and married a free Black woman named Clarissa Mason. They moved to the town of Essex and started a family. To earn a living, Sawney Freeman cobbled together jobs in agriculture, in local shipyards, and as a musician.

Looking back on this period in his 1864 book History of Durham, Connecticut, author William Chauncey Fowler recounts hearing Sawney Freeman perform at a celebration for the Black community: “They had their balls, in imitation of the whites. One of these balls the present writer witnessed at the Wilkinson house, just south of the Goodrich house. Sawny [sic] Freeman, whom some must now remember, was their musician. He accompanied his violin with a sort of organ, which he played with his foot. It was somewhat, in its effect, like the Aeolian attachment to the piano. It added greatly to the volume of the music. At this ball, besides contra dances they had jigs and reels. They danced with great agility and spirit.”

Concerts and balls exclusively attended by Black people were a phenomenon on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1764, the London Chronicle described a similar event: “Among the sundry and fashionable routs or clubs that are held in town, that of the Blacks or the Negro servants is not the least. On Wednesday last, no less than fifty-seven of them, men and women, supped, drank, and entertained themselves with dancing and music, consisting of violins, French horns, and other instruments at a public house in Fleet Street till four in the morning. No Whites were allowed to be present, for all the performers were Blacks.”

A Newspaper Ad, a Major Discovery

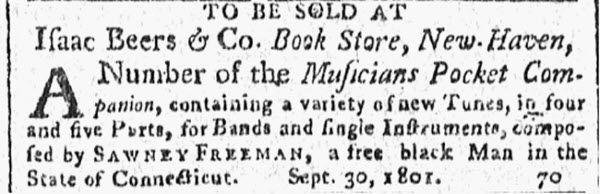

In 1801, an advertisement was published in the Connecticut Journal: “To be sold at Isaac Beers and Co. Book Store, New Haven, A Number of the Musicians Pocket Companion, containing a variety of new Tunes, in four and five Parts, for Bands and Single Instruments, composed by SAWNEY FREEMAN, a free black Man in the State of Connecticut. Sept. 30, 1801.” (Volumes with titles like “Pocket Companion” were generally compendiums of pieces — sometimes all in a single genre or with a single purpose, and, in other cases, in an assortment of genres.)

The ad’s 1801 date positions Freeman’s publication as the earliest known published music by a Black composer in the U.S. It is unclear who was responsible for printing the volume.

Unfortunately, no printed copies of Sawney Freeman’s the Musicians Pocket Companion have surfaced. But the researchers from St. John’s Episcopal Church found that handwritten copies of his music were located in a collection at the Watkinson Library on the campus of Trinity College in Hartford.

The library holds the so-called Gurdon Trumbull Copy Book, copied in 1817, containing more than a dozen tunes composed by Sawney Freeman. The words “by Sawney Freeman” or “by S. F.” can be clearly seen beside the music. The tunes have names like “St. Alban’s,” “Washington’s Farewell,” “Solemnity,” “Winter Piece,” and “The New Death March.”

As was common with instrumental pieces of the period, some of Freeman’s titles, including “The Rays of Liberty,” “Liberty March,” and “The Union of All Parties,” were not so much descriptive as evocative for listeners, thus making his music more memorable and connecting it to local or personal history. Several titles correspond with the names of Masonic Lodges in the region, underscoring the links between Freeman’s music and local audiences.

The manuscript reflects the needs of a gigging musician who required music for a variety of occasions and who wanted to stay abreast of the latest songs and dances. The volume shows that Freeman composed in a variety of genres including dances such as jigs and reels as well as marches.

The manuscript also includes popular songs, from “Polly, Put the Kettle On” to “Yankee Doodle.” Some pieces draw on a fiddling tradition, while others are oriented more toward the church or military music. Some of the pieces are for solo violin, while others are scored for ensembles of five or six instruments. The melody of the tunes by Sawney Freeman is in the tenor line, which also stands out by providing rhythmic variety and interest. In some cases, there are both solo and ensemble versions of the same melody.

Sawney Freeman’s music had its first modern-day performance in 2022 at St. John’s in Essex. In 2024, the music was recorded in New Canaan as part of the Connecticut Public Broadcasting Series Unforgotten: Connecticut’s Hidden History of Slavery.

Not all the compositions in the Trumbull manuscript are marked with Freeman’s name, although much of the music in the volume does not name any composer. (Only one other piece, titled “Federal March,” has a composer’s name. Difficult to read, it appears to be “Wattles,” the name of a family who lived in the southeastern part of the state from the late 1600s through the mid-1800s.) This raises the question of who would have used notated settings of Freeman’s music. As noted, Freeman no doubt learned music initially via oral traditions, rather than by reading Western musical notation.

However, it is perfectly possible that he learned to read and write in staff notation at some point. In an online EMA article from February 2023, Rebecca Cypess suggested that the Black British composer Ignatius Sancho used musical notation as a medium of self-expression and the communication of an antiracist critique of white society. Sancho’s music, published as early as 1767, would likely have been used by white musicians as well as by Black musical ensembles that performed at the all-Black dances of the sort mentioned by the London Chronicle. Similarly, Freeman’s notated music may well have been used by both white and Black ensembles, raising the possibility that other Black musicians in the U.S. played from notation as well as by ear.

The handwritten manuscript at the Watkinson Library is part of the collection of Gurdon Trumbull, a wealthy merchant from Stonington, Conn. His family took an interest in abolition, and members of the Trumbull family collected a variety of material regarding local Black residents. The copybook likely became part of the Trinity College collection because Trumbull’s son, James Hammond Trumbull, was the first librarian at the Watkinson.

Sawney Freeman died in 1828. He and his wife Clarissa are buried in Riverview Cemetery in Essex, Conn. There is much left to learn about Sawney Freeman and the many other Black musicians of 18th-century America. Now, after centuries of silence, Freeman’s music can be heard again.

Diane Orson is a special correspondent with Connecticut Public and a contributing reporter to National Public Radio. She reported and co-produced Unforgotten: Connecticut’s Hidden History of Slavery, which received the 2024 Connecticut Broadcasters Award for “Best Use of Digital Media.” She is also a freelance violinist and was involved in the first modern performance of Freeman’s music.

Musicologist and historical keyboardist Rebecca Cypess is Dean of the Undergraduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Yeshiva University. Her publications include Women and Musical Salons in the Enlightenment (2022) as well as articles on the 18th-century Black British composer Ignatius Sancho.