Cover Article in the January 2020 issue of EMAg, the Magazine of Early Music America

In this and coming issues, EMAg will feature makers of early-music instruments, celebrating artisans who design and craft wind, string, keyboard, and percussion instruments based on historical models. Some of these makers are players themselves, and all interact closely with those who collect, play, and love their instruments.

Photo courtesy of the Von Huene Workshop

As someone who has played recorder and historical woodwinds for half a century, and as a proud member of the Performance Practice Police (defined below), I have been asked to write about why historical instruments are so essential to the field of early music, the special relationship between makers and players, and the importance of designing, making, and playing these instruments. Although written from the perspective of one who blows into a pipe, players of other instruments no doubt will recognize shared experiences.

Those who question why we play early instruments sometimes follow our gushing replies with the commonplace, “Wouldn’t Bach have played a piano if he had had one?” Upon hearing the crumhorn for the first time, my Great Aunt Ella posed a more eloquent version of this viewpoint with the observation, “Sounds like something they played ’til they got something better.” Of course, Bach would have written for piano, but he didn’t, and the ways in which he challenged the idiomatic nature of each instrument is part of the beauty of his music. And yes, the crumhorn was supplanted by other instruments, but it played an important function in its own context during another era fascinated with instrumental variety and innovation.

In retrospect, my own experience is that we are exploring instruments that were played “until they got something better” while simultaneously evolving how we play specific instruments and their music every time modern makers and players “get something better.” These moments of discovery and change—both “back then” and today—offer the most fascinating insights.

Allow me to enlist the paradox of Zeno’s Historically-Informed-Performance Tortoise. You know the old paradox, in which Zeno’s tortoise moves halfway toward a pond. Upon moving again, it is once again halfway there. Each time it creeps along, its excitement at arriving closer to the pond is countered by the realization that it is once again only halfway to the pond. Zeno’s HIP Tortoise excitedly discovers a new instrument and some new truth it offers about how to perform the music for which it was intended, only to discover a new instrument that compels yet another surge toward the tantalizing mythical pond of “historical performance.”

Shawms and Sackbut-Playing Tortoises

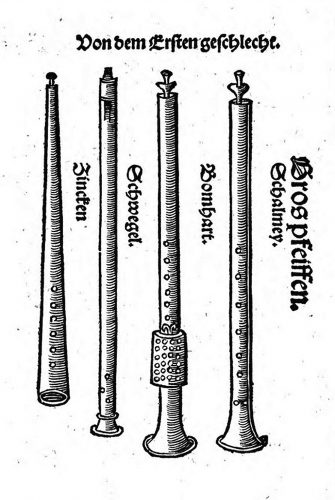

The first shawm I played in 1979, my first year of college, was the latest model, hot off the press. Based on measurements made by Herb Myers in 1968 at the Musical Instrument Museum in Brussels, it represented a fundamentally different design than the “Deutsche pommer,” a skinny, oboe-like shawm with a staple made by Moeck and played in collegium ensembles throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s, and now found gathering dust in back closets of colleges across the country.

But my shawm was altered from the original models in Brussels. In order to fit with other instruments in early-music ensembles, the treble and alto were made to play in C and F, like soprano and alto recorders, and pitched at A=440. Nonetheless, this “Brussels” shawm served into the 1980s, representing something of an industry standard in early-music ensembles, in part because it could blend in pitch and volume with other instruments.

Photo by Barbara Prescott

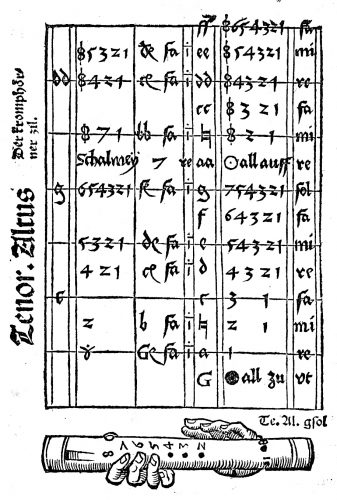

The HIP tortoise took a bumpy step with the realization that the Brussels schalmei (treble shawm) and its alto partner, the bombard (alto shawm), were pitched a step higher, in D and G, and that they were not meant to play with other instruments, but rather originated in the 15th century as part of the alta capella, a wind ensemble that included a schalmei in D, one or two bombards in G, and a slide trumpet or sackbut (trombone), with the addition of cornetto and dulcian in the 16th century. This higher pitch solved tuning problems on the shawm, producing a much brighter sound that met with mixed reviews among audiences and colleagues. Playing a step higher also means that trombonists must transpose a step above their B♭tuning in order to play with shawms. Moreover, the ensemble would play either a step or fifth higher than written pitch, based on the range of any given composition. The schalmei player would thus play either C or G fingerings, while the bombard player would think in C or F. These are relatively easy transpositions for recorder players but more difficult for a trombonist used to thinking in B♭.

The HIP tortoise took another lively step with the realization that surviving historical shawms actually sound a half-step higher than modern pitch, around A=466, much like surviving Renaissance recorders. Adopting this pitch solved yet more tuning problems on the shawm, making the sound brighter (once again to mixed reviews). Now the trombonist would no longer read up a step from B♭ but would adopt the historical pitch standard common through the 17th century, with the fundamental note of the instrument sounding at A=466. The jury is still out on whether one can hear the difference between a player thinking in B♭ or A, but the transition raises fascinating questions about how the perception of pitch informs the performance of historical brass instruments.

But wait! The tortoise plods on: Trombonist Adam Bregman suggests that 15th-century sackbut players weren’t thinking a “step higher” than A-466 after all. Maybe they were just thinking in G=520. By imagining the pitch of the instrument this way, the fundamental slide position of the sackbut corresponds precisely to the bottom G of the bass clef, or Gamma-ut, the fundamental tone of contemporary music theory. For Bregman, this realization is something like a Copernican discovery in which seemingly complex issues yield to simple and elegant solutions. It also aids in visualizing slide positions in terms of 15th-century solmization, with syllables applied to each note. This in turn helps in adopting historical tuning systems.

When a player or ensemble director asks for advice about purchasing shawms, the prudent compromise might be to order schalmei and bombard in D and G at A=440, but this choice is based in part on a desire to have shawms match A=440 as a lingering industry standard among many Renaissance ensembles. Some schalmei makers copy an original instrument pitched around A=466, moving the tuning holes to make the instrument play a half-step lower at “modern pitch,” a choice that fundamentally affects how the instrument plays. This is one reason why I argue for hopping on the tortoise and moving up to “high pitch.” (American makers of fine shawms and bombards based on historical instruments include Bob Cronin and his successor Rufus Acosta, Paul Hailperin [in Germany], and Leslie Ross.)

Single vs. Forked-Fingering Tortoises

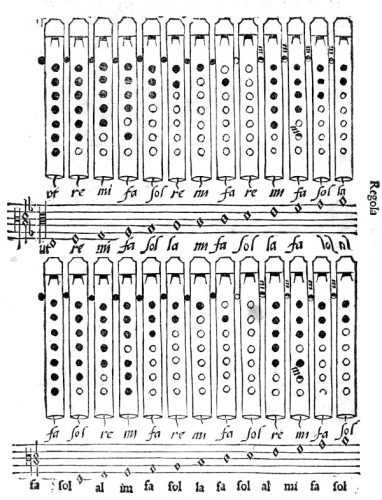

Probably no issue better exemplifies how conceptions about performance and instrument-making interact than that of the fourth note on the bombard (alto shawm). Martin Agricola’s Musica instrumentalis deudsch (1529) provides the only surviving fingering chart for shawm, conflating the fingerings with contemporary recorders, noting minor differences between recorders and shawms (as instruments with no thumb holes). In general, the schalmei works beautifully with Renaissance recorder fingerings.

But the bombard seems to present a problem. Just as on the recorder, if you play an ascending scale from the bottom note (in this case, imagining the bottom note as F), lifting each finger will raise the pitch by a whole tone. When lifting the three bottom fingers, however, the fourth note will sound somewhere between B and B♭. (On bagpipes with a drone on “G”, for example, this fourth note sounds as a “neutral third” above the drone and is common in folk music.) But on recorders and other instruments using “Western” scales, players typically cover the second finger or some combination to lower that note to Bb, or play C above, skip a hole, and add one or more fingers below to create a B natural. All of these cross fingerings are nothing more than alterations of the “natural” pitch of a given pipe length to adjust to a common tuning system.

Opera intitutula Fontegara (1535)

The bombard is no exception. When played with a single fingering, the fourth note is often perceived as simply too high and in need of adjustment. There are two common and opposing solutions to this issue on the bombard. One is to adjust the tuning of the instrument so that it functions with a fork fingering, much like a Renaissance recorder. This strategy is supported by Agricola’s fingering chart, which shows a forked fingering for all wind instruments in a single chart. One problem with this approach is that the maker must adjust other parts of the instrument to make the forked fingering work.

The second strategy, espoused by Herb Myers, is to play the fourth note of the bombard with a single finger but in a relaxed manner so that this note naturally matches the pitch of the forked fingering on the Renaissance recorder. This approach of adjusting to fit the given fingering is based on surviving instruments and on a premise that the fourth note should be a tad higher than equal temperament, sounding as a fa above a slightly lower mi. I fall squarely into the second camp, but there is evidence to support both of these approaches, and presumably no one will ever come to blows over such minor differences. The point of this wonky detail is to illustrate how one perceives a single issue can fundamentally affect decisions by both makers and players.

Recent discoveries about the shawm offer a new perspective about the development of the instrument over the course of the Renaissance and Baroque eras, one that corresponds closely to other woodwind instruments. With the discovery of three shawms in the hands of angel sculptures in the roof of Freiberg Cathedral (built 1585-94), we now have a surviving instrument in C at A=466, revealing a transitional stage in the development of the instrument. And the tortoise steps again.

While it is exciting to play a variety of historical wind instruments, equally fascinating are our leaps in understanding the amount of headway instrument builders were making hundreds of years ago. Remember those dusty Deutsche pommers? They are enjoying a comeback at the hands of ensembles like Piffaro, which is exploring its role in 17th- and 18th-century music. And musicians are still probing the potential of the “Mary Rose” douçaine, the sole surviving example of a cylindrical shawm found in the famous Tudor shipwreck and lovingly copied by Phil and Gayle Neuman.

My own HIP tortoise reminds me that, at the age of 12, I woke from a dream of a room filled with woodwind instruments, with the choice of going outside and leaving the instruments behind or staying inside forever and learning to play. At the time, the choice was clear, and half of the dream is still coming true; the instruments do let me outside from time to time. For those who enjoy the privilege of playing early-music instruments, from finely crafted copies of recorders to the fantastical wooden beasts made by Phil and Gayle Neuman—complete with animal heads and astonishingly sweet and low rumbling sounds—instrument makers play a special role. To paraphrase the British poet Arthur O’ Shaughnessy, they are the true makers of dreams.

Since his debut with the Renaissance Trash Trio and The Wombats and Gonfaloons in 1975, Adam Knight Gilbert has played historical woodwinds with The Mannes Camerata, Ensemble for Early Music, Waverly Consort, Piffaro, and Ciaramella, which he co-directs with Rotem Gilbert. He directs the Early Music program at the USC Thornton School of Music, where he teaches musicology and researches Renaissance counterpoint, composition, and musical symbolism.

Since his debut with the Renaissance Trash Trio and The Wombats and Gonfaloons in 1975, Adam Knight Gilbert has played historical woodwinds with The Mannes Camerata, Ensemble for Early Music, Waverly Consort, Piffaro, and Ciaramella, which he co-directs with Rotem Gilbert. He directs the Early Music program at the USC Thornton School of Music, where he teaches musicology and researches Renaissance counterpoint, composition, and musical symbolism.

Your Input is Instrumental

Questions facing both players and makers are potentially fascinating. Therefore, beyond merely profiling makers of historical instruments, we would like to pose some of the following:

- To what extent is your work historically informed, and where do you part company with your historical counterparts to make your instruments work in the modern world?

- For whom do you make your instruments, and how does that affect your choices?

- What have you learned along the way that has changed your approach?

- What information would you most like to share with modern players of your instruments?

- What questions about your instruments and those of the past keep you up at night?

Because players perform such an important role in this discussion, we would also like to hear about their insights into the marriage between historical instruments and performance practices. Finally, to all of our readers, your questions and comments can inform us as we interview makers and players around the country. To that end, we invite you to share you questions or comments in the discussion below.